UAE – time to accelerate LNG expansion plans [Gas in Transition]

Two announcements in May carried importance for the UAE’s attempts to achieve gas self-sufficiency and expand its LNG export capacity to take advantage of growing demand for the fuel.

First was the announcement that its planned second LNG plant, with proposed capacity of 9.6mn mt/yr, will be built at the Ruwais downstream oil and gas hub in Abu Dhabi rather than in Fujairah. The new location came as something of a surprise, particularly given the seizure by Iran of two Greek-owned oil tankers, the Prudent Warrior and the Delta Poseidon, in the preceding days.

The seizures highlight the continued risk to shipping presented by the Strait of Hormuz, the narrow channel between Iran and the Musandam governorate of Oman.

One of Fujairah’s key advantages is that it provides access to the Gulf of Oman east of the Strait. In the event of the Strait’s closure to shipping, UAE LNG exports would have a better chance of continuing uninterrupted.

The issue has long been of concern. The security provided by an export point in Fujairah lay behind the construction in 2012 of the Abu Dhabi oil pipeline, which runs from the Habshan onshore oil field to Fujairah.

However, concerns over the Strait’s vulnerability appear to have been abandoned in the decision to locate the new LNG plant at Ruwais.

In May last year, engineering company McDermott was awarded a front-end engineering and design contract for the LNG plant in Fujairah. The plan was a fully electric-drive system, allowing for a low emissions basis for LNG production. However, it was not made clear whether the plant would have dedicated renewable energy capacity, or would source electricity from the UAE grid, where the generation mix is changing, but is still heavily dependent on gas-fired generation.

At the time of the FEED contract, McDermott expected engineering, procurement and construction contracts to be awarded this year, but these may face delay as a result of the changed location.

The UAE’s existing LNG plant consists of three trains with a total capacity of 5.8mn mt/yr. It is located on Das Island about 100 km northwest of the UAE mainland in the Persian Gulf, west of the Strait of Hormuz. The completion of Trains 1 and 2 in 1977 made it only the fifth modern LNG plant to be constructed. A third train was added in 1994.

Gas balance set to improve

UAE gas demand has risen fast over the last 25 years, driven by a rapidly expanding power sector. By the turn of the millennium, gas demand was outstripping gains in production and new sources of gas were needed. These came initially from Oman via the Al Ain-Fujairah gas pipeline, built in 2003 to supply gas-fired generation and desalination plants in Fujairah.

This was followed by the Dolphin gas project, which was constructed in 2006. This brought North Field gas from Ras Laffan in Qatar by subsea pipeline to Taweelah on the UAE’s western coast. Gas was distributed further into the country via the Taweelah-Fujairah gas pipeline. Qatari gas now also reaches Oman following the reversal of the Al Ain pipeline in 2008.

LNG exporter turns importer

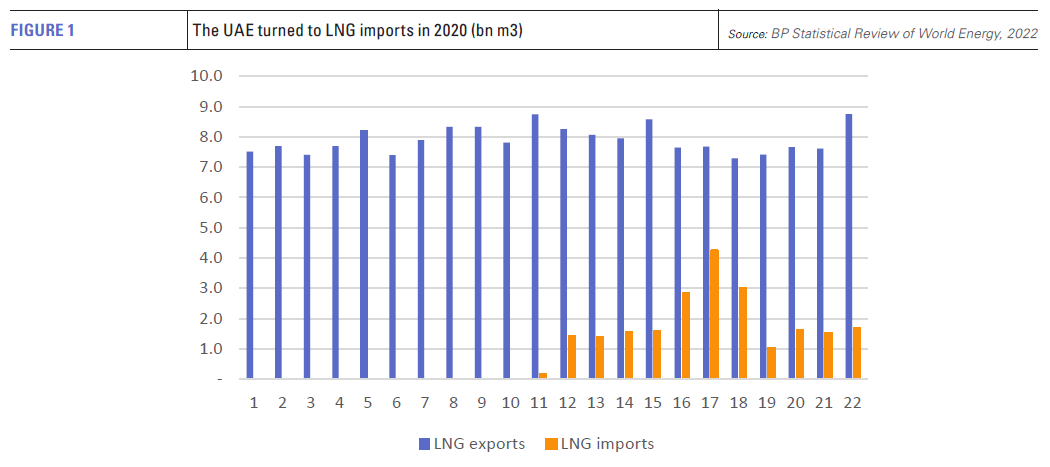

However, even with supplies ramping up via the Dolphin pipeline, the UAE needed more gas, and, in 2010, Dubai imported its first LNG cargo (see figure 1). Despite sitting on huge gas reserves, the UAE had joined the select group of countries which both export and import LNG.

The second announcement in May was an extension to the time charter of the Floating Storage and Regasification Unit (FSRU) Explorer, which serves Dubai. The vessel is chartered by the Dubai Supply Authority (DUSUP) from Excelerate Energy and located at the Jebel Ali LNG import terminal.

The FSRU was built in 2008 and substantially upgraded in 2015, including new HP vaporizers and pumps, a dual-fuel diesel generator and an LNG bunker port. The improvements increased the terminal’s send out capacity from 690mn ft3/d to 960mn ft3/d.

DUSUP has extended its charter agreement by five years from the end of its current contract, which expires in late 2025. With a contract now in place until the end of 2030, DUSUP clearly expects to continue importing LNG until the end of the decade, or at least wants to secure the capacity to do so, should it have to.

New power generation mix

Curbing domestic demand growth for gas is a key element in the UAE’s self-sufficiency plans. The UAE’s electricity system has historically been entirely dependent on gas-fired generation. As a result, its gas demand has until recently closely mirrored power consumption.

Gas-for-power generation more than doubled between 2000 and 2010, rising from 39.9 TWh to 93.9 TWh, before increasing further to 134.7 TWh in 2018 and 2019.

Diversification into two other forms of electricity generation – nuclear and solar – saw the first decline in gas for power use in 2020 and then, much more substantially, in 2021, as nuclear generation rose to 10.5 TWh and solar to 5.1 TWh.

The UAE now has three South Korean-built nuclear reactors in operation, providing 4,019 MW of capacity and a fourth, with 1,310 MW, in the final stages of commissioning. The first unit was connected to the grid in August 2020, the second unit in September 2021 and the third in October 2022.

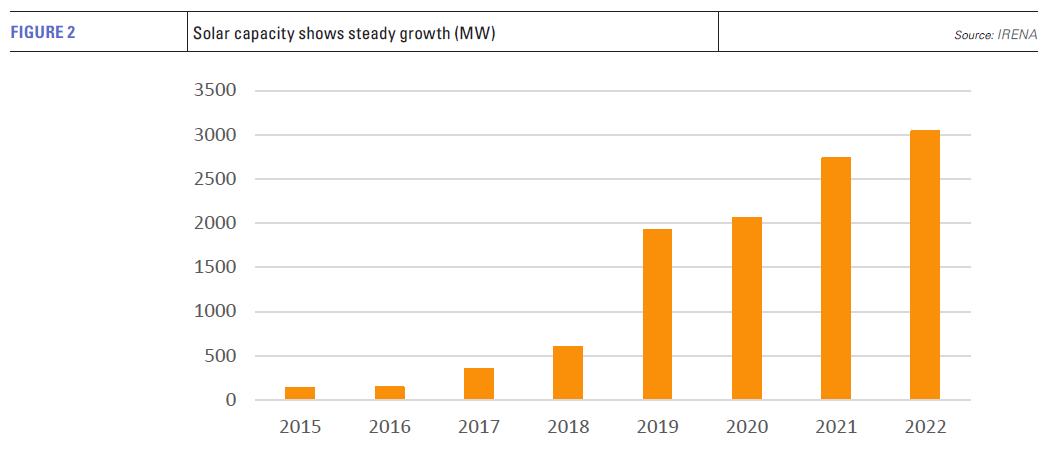

The UAE has also embraced solar power, recording some of the lowest bids for new solar capacity in the world (see figure 2). Capacity at the end of 2022 had reached 3,040 MW, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency.

Solar capacity is set to rise further as the 2.1-GW Al Dhafra project comes fully online. The giant project is expected to go into service officially this summer. A robust project pipeline suggests the UAE’s solar capacity could reach 8.5 GW by 2025, most of which will be sited in Abu Dhabi and Dubai. The Mohammad bin Rashid Al Maktoum solar farm is being developed in phases and will total 5 GW of capacity alone by 2030.

Wind power is also expected to enter the mix. An area in the Hatta area of Dubai was identified in 2021 for the country’s first wind farm, which is expected to have a capacity of 28 MW.

Dubai made a venture into coal-fired generation with construction of the 2.4-GW supercritical Hassyan coal-fired plant. Construction started in 2016 and two of the plant’s 600-MW units were reported to be complete in 2021. However, the plant was switched to run on natural gas from February 2022. All four units are expected to be online by the end of this year.

The fuel switch increased the country’s dependence on imported gas, but was more in line with its emerging greenhouse gas emissions policies. The UAE has a target of generating half of its electricity from renewable energy by 2050 – the addition of a major coal plant would not have helped its emissions profile.

New gas production

Demand-side curbs have been accompanied by major plans for new gas production.

Last year, the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) announced plans to form ADNOC Gas, bringing together ADNOC Gas Processing and ADNOC LNG into one entity. A five-year plan for capital expenditure of 550bn dirhams ($150bn) was approved for the period 2023-2027. A 4% stake in the new company was floated earlier in the year on the Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange, raising $2.5bn. A second initial public offering is underway for 15% of ADNOC Logistics and Services.

The UAE currently imports 2bn ft3/d of gas (20bn m3/yr) from Qatar, which meets almost a third of demand. In 2021, Dubai also imported 1.7bn m3 of LNG. However, the country’s gas balance is set to change.

The Ghasha Mega project, the world’s largest sour gas development, comprises the Ghasha, Hail, Hair Dalma, Satah, Bu Haseer, Nasr, SARB, Shuwaihat and Mubarraz gas fields. The increased spending plans announced last year are designed to accelerate the project, which was previously scheduled to start production in 2025 with output rising to 1.5bn ft3/d by 2030.

In addition, the Ruwais Diyab onshore gas field, which lies in the Ruwais Diyab unconventional gas concession, is expected to see a commercial start in 2025 and reach production of 1bn ft3/d by 2030 and 2bn ft3/d at its peak in 2035. The field is operated by France’s TotalEnergies, which has a 40% stake in the project.

In addition, the Ruwais Diyab onshore gas field, which lies in the Ruwais Diyab unconventional gas concession, is expected to see a commercial start in 2025 and reach production of 1bn ft3/d by 2030 and 2bn ft3/d at its peak in 2035. The field is operated by France’s TotalEnergies, which has a 40% stake in the project.

A further boost to the UAE’s gas plans was a major discovery in 2020 in Jebel Ali, which is estimated to hold some 80 trillion ft3 of reserves across a 5,000 square-km area straddling Abu Dhabi and Dubai. The find was the largest worldwide since the discovery of the giant Galkynysh field in Turkmenistan in 2005.

A significant discovery was also made in Sharjah the same year, where Italian major Eni, which has a 25% stake in the Jebel Ali discovery, found the Mahani reservoir. According to the company, the first well flowed 50mn ft3/d of gas and condensate. Although still under evaluation, production from the field started up in early 2021, just one year on from the initial well. Further discoveries in Abu Dhabi’s Offshore Block 2 also hold promise with estimated gas potential of 2.5-3.5 trillion ft3.

Current projects underway both upstream and in the power sector suggest the UAE will become self-sufficient in gas sometime between 2025 and 2030, at which point it will still be in receipt of Qatari gas imports. The contract for pipeline gas from Qatar runs until 2032.

The major new discoveries made in the last two to three years underline the size of the country’s gas potential, as well as promising a lower cost base than the current sour gas developments. This, in turn, implies that it needs to proceed directly with its LNG expansion plans, if it is to get surplus gas, either domestic or imported, to wider markets in a timely manner.