Indonesia: Southeast Asia’s LNG wild card [Gas in Transition]

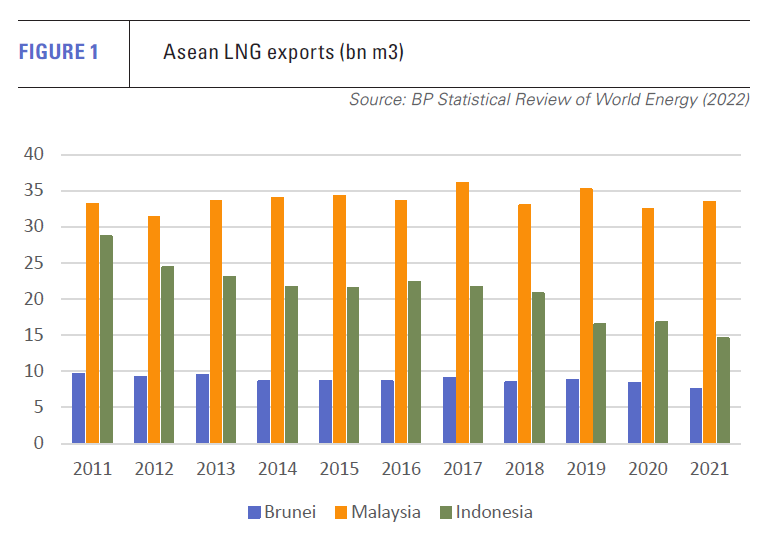

Indonesia is the least predictable member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in terms of its involvement in the global LNG market (see figure 1). Most members have a well-established role -- exporters with limited or no growth prospects, or current or future importers with, in most cases, relatively modest demand potential.

Brunei, for example, saw its exports decline from 9.6bn m3 in 2011 to 7.6bn m3 in 2021, according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy. Malaysian exports were more or less level over the same period, rising from 33.2bn m3 to 33.5bn m3.

This stability reflects the fact that the LNG industries of both countries are based on mature gas developments and long-term contracts.

Among the importers, Singapore has an importance beyond the amount of LNG it consumes because of its pivotal role in the regional LNG market. But LNG imports that reached 5.7bn m3 in 2020, falling to 5.1bn m3 in 2021, are unlikely to grow at a substantial pace.

Meanwhile, forecasts for Thai LNG demand have often projected substantial growth.

Strong growth in energy demand met in large part by LNG has been forecast against a backdrop of falling domestic gas production; uncertainty over piped gas imports; reluctance to become over-reliant on electricity imports; and the country’s increasing reliance on gas-fired power generation, given the planned phase out of coal-fired capacity.

This has led to considerable investment in Thai LNG import capacity. The state-run PTT’s 11.5mn mt/yr Map Ta Phut terminal was joined in March by the 7.5mn mt/yr MTP-2 terminal at Nong Fab. Initial contracts were also awarded in late 2022 for a 10.8mn mt/yr project being developed by Gulf MTP, a consortium headed by Gulf Energy Development, which is also constructing 7.8 GW of LNG-fired, combined-cycle generating plant.

Thai LNG imports did grow from 1.1b m3 in 2011 to 9.2bn m3 in 2021. But this is relatively low given its LNG import capacity, and the limited alternative energy options. Moreover, enthusiasm for the fuel has waned since 2022 because of LNG’s high spot market price and price volatility. The emphasis has instead shifted to reviving domestic gas production and kick-starting Thailand’s renewable energy programme by offering generous feed-in tariffs in new rounds of bidding for solar and wind capacity.

The picture is not dissimilar in the Philippines and Vietnam. Both fledgling importers, LNG growth prospects in the two countries should be bright because of their inadequate domestic gas production, limited alternative energy resources, and official shifts away from coal-fired generation. But, over the past year or so, high LNG prices and the lure of renewables appear to have dampened their enthusiasm for the fuel.

Indonesia could prove the exception

High prices have seen LNG run up against the deeply-ingrained caution evident among Asean members – a caution Indonesia shares. But whereas most Asean countries fear an over-reliance on energy imports, Indonesia’s concern relates to energy exports.

The country was for many years the world’s largest single LNG exporter, accounting for about two-fifths of global trade at the start of the 1990s. It remained the leading exporter until 2006, but had fallen to eighth place by 2021, when its exports totalled only 14.6bn m3 – about half the level recorded in 2011.

The decline partly results from the 1945 constitution, which prioritises the domestic use of commodities rather than their export. Proponents of the domestic market obligation add that this is economic realism as much as constitutional probity – they say gas should be used within the country to manufacture goods for export, adding value and creating employment, rather than exported as a raw material to the benefit of industrial competitors.

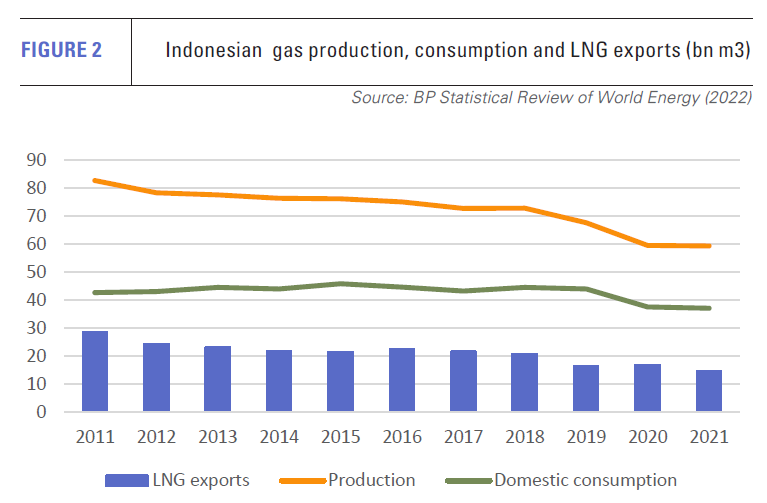

The priority given to gas use in the domestic market has become more significant in recent decades because much less gas is being produced. Domestic output fell from 82.7bn m3 in 2011 to 59.3bn m3 in 2021 (figure 2).

The fall reflects years of underinvestment in the gas sector, with spending on exploration by private and foreign investors dropping in particular. The country’s proven and potential reserves totalled 4.3 trillion m3 in 2011 and 4.1 trillion m3 in 2016. But this total had collapsed to 1.7 trillion m3 by 2021, according to the Directorate General of Oil and Gas.

Limited movement on Abadi

Things are little better further up the chain, as demonstrated by the glacially slow development of the Abadi gas field and LNG project. While the project made some progress in April, it has been stuck at a relatively early stage of development for a quarter of a century.

Japan’s Inpex won the bid for the offshore Masela Block in 1998. As currently envisaged, the project includes development of the 360bn m3 Abadi field, a 9.5mn mt/yr onshore LNG plant -- backed by a sales agreement with state electricity company PT PLN -- and gas pipelines to supply 4.2mn m3/d to local consumers.

A revised development plan for Abadi was submitted in April, the main change being the requirement for carbon capture and storage. A final investment decision is sought in the late 2020s for a start to production in the early 2030s.

With existing fields depleting fast and few new projects on the horizon, gas production is set to fall further. Meanwhile, regardless of the domestic market obligation, consumption fell from 42.7bn m3 in 2011 to 37.1bn m3 in 2021.

Most gas is used in the industrial and power generation sectors. It accounts for a third of industrial energy use, according to the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, although demand outstrips availability in most industrial sectors and much of the country.

Power sector trends

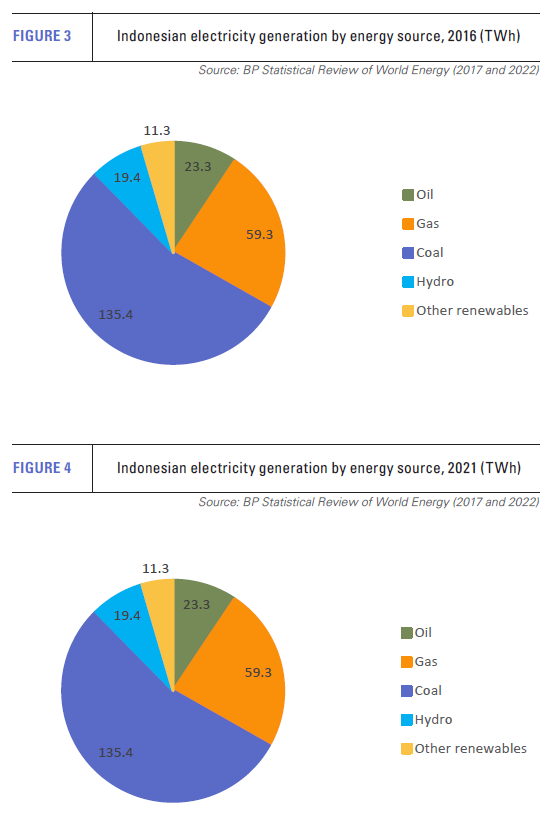

In the power sector, gas is seen as key to eliminating remaining oil-fired generation and helping meet the burgeoning growth in electricity demand (see figures 3 & 4). This is officially projected to increase by 4.4%/yr to 2030.

But little progress has been made on this front; in fact the reverse. In 2021, gas accounted for well under a fifth of total electricity output, compared with almost a quarter in 2016. Gas’s falling share of electricity generation was offset by increased coal use, which accounted for 61.4% of total power output in 2021, compared with 54.5% in 2016.

However, coal use is under pressure from Indonesia’s climate targets. Replacing the fuel responsible for three-fifths of electricity output and two-fifths of total primary energy supply will be, to put it mildly, difficult.

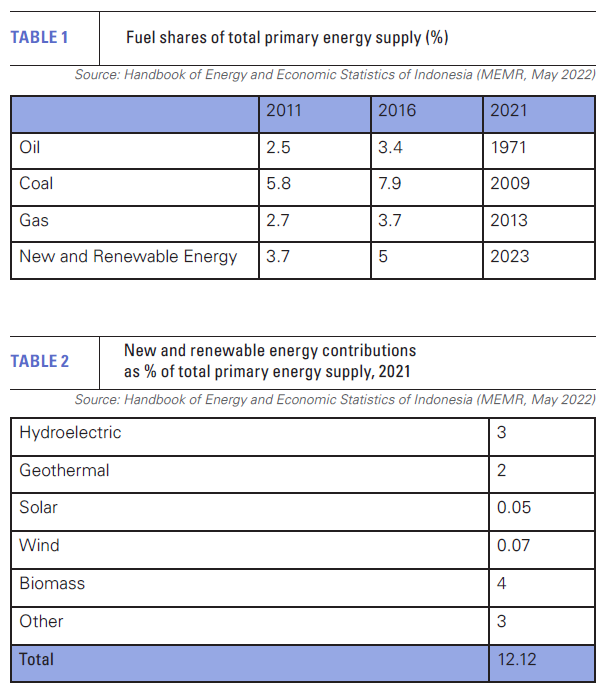

This is especially so given that renewables – the preferred option to replace coal and gas in most of Asean – offer limited scope in Indonesia in the near to medium term. Indonesia has substantial renewable potential, but little has been implemented to date. Hydro, geothermal and ocean energy projects are capital intensive and have long gestation periods. They have struggled to secure financing and approvals.

As for solar and wind, they together accounted for under 0.2% of primary energy supply in 2021. The financing and regulatory issues that dog all Indonesian projects are compounded in the case of solar and wind by the difficulty of securing project sites in the densely-populated country.

If a substantial amount of coal is to be displaced in line with Indonesia’s climate commitments, it thus seems certain that a substantial increase in gas use will be needed as the bridging fuel during what could be a long transition to a renewable-based energy system.

Jakarta wants as much of this gas as possible to be produced locally. Economy Minister Airlangga Hartarto said in November 2022 that domestic output should reach 124bn m3 by 2030 – more than double the current level. But the decades-long lack of investment in the gas sector means an increase on this scale, at least currently, appears unrealistic.

Potential for LNG imports

Much of the gas would thus have to be imported and, with few realistic prospects for piping gas from overseas, this would mean LNG. Some regasification facilities already exist, with former liquefaction plants such as Arun having been reconfigured to bring in the fuel.

New capacity has also been commissioned or is under development in Java, Bali and Sumatra. Based on floating storage and regasification units, with power plants as their anchor or only customer, these facilities are primarily intended to move domestic gas around an archipelago where pipelines are often unfeasible.

But, with the facilities in place, LNG could equally well be imported.

Small-scale LNG might tip the balance

There could also be a substantial increase in LNG capacity, if government plans for a major programme of small-scale LNG facilities take off. Being pursued under the $20 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership signed in November 2022 between Indonesia and a group of donor countries, the programme is predicated on the conversion of some of the country’s 5,200 diesel power plants to gas firing.

In the first instance, 33 larger diesel generators would be converted to gas firing and fuelled with LNG delivered to small regasification plants. The plants would also distribute gas to other users in the vicinity, most of which would be in eastern Indonesia.

Small LNG terminals and tankers are relatively expensive, meaning they tend to be uncompetitive compared with the continued use of oil or investing in renewables. But with limited interest in renewables, the possible availability of subsidies and the potential for multiple delivery points to reduce shipping costs, development of the projects could result in significant additional LNG demand.

If the programme does take off, and if coal use is scaled back as planned, there would be a substantial increase in Indonesian gas demand. Both are big ‘ifs’, but, if they do occur, Indonesia could quite quickly switch from LNG exporter to net importer.