Pakistan’s LNG options [Gas in Transition]

Pakistan is one of the most important second-tier markets for LNG growth in Asia. However, there are question marks over how much LNG it will use, given issues including the slow implementation of new regasification and gas distribution capacity.

The importance of gas and LNG as integral parts of the country’s energy mix is accepted across the political spectrum. This is not surprising given, firstly, the continuing downward trend in domestic gas production and, secondly, the limited availability of alternative energy sources to fuel Pakistan’s power stations, industrial, commercial and administrative facilities, and residences.

Domestic gas crunch

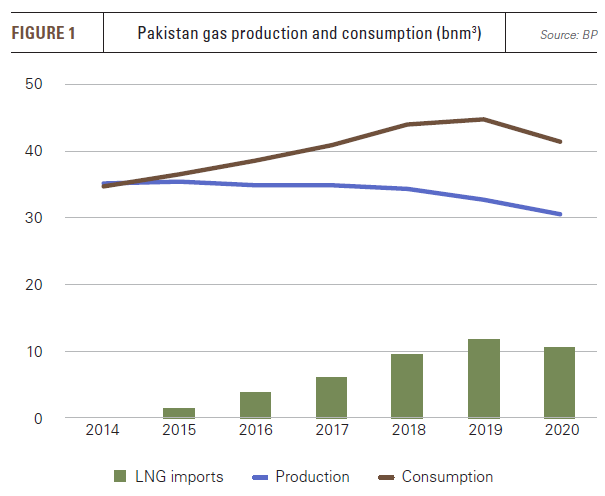

Pakistan had 0.4 trillion m3 of proved gas reserves at the end of 2020, representing a reserve-to-production ratio of just 12.6 years, according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2021. Domestic output was 36.6bn m3 in 2012, but, by 2020, had fallen to 30.6bn m3 (Figure 1). By late 2021, it was equivalent to less than 29bn m3/year.

Production was well below consumption of 41.2bn m3 in 2020 and peak consumption of 44.5bn m3 in 2019. The gap has been filled by LNG imports, which started in 2015 and reached 10.6bn m3 in 2020, according to BP data, with two-thirds of supply coming from Qatar in that year.

The government is urgently seeking to revive domestic gas output. Prime minister Imran Khan said in December 2021 that issuing new gas exploration licences should be given top priority. However, based on past precedent, the prospects for success are not good.

In recent years, few discoveries have been made and the exploitation of shale gas resources has proved particularly problematic. In late December, energy minister Hammad Azhar told a press conference that gas fields are depleting at about 9% annually.

Meagre alternatives

Falling gas output is compounded by the limited availability of alternative fuels to feed the burgeoning energy market. The electricity sector is a case in point. While power production grew from 99.4 TWh in 2010 to 137.8 TWh in 2020, it remained well below potential demand because of limited generating capacity and energy supplies.

Pakistan’s much-vaunted nuclear power programme has made slow progress since its inception and nuclear generation is currently limited to the output of five reactors with 2.24 GW of capacity at Chashma and Karachi.

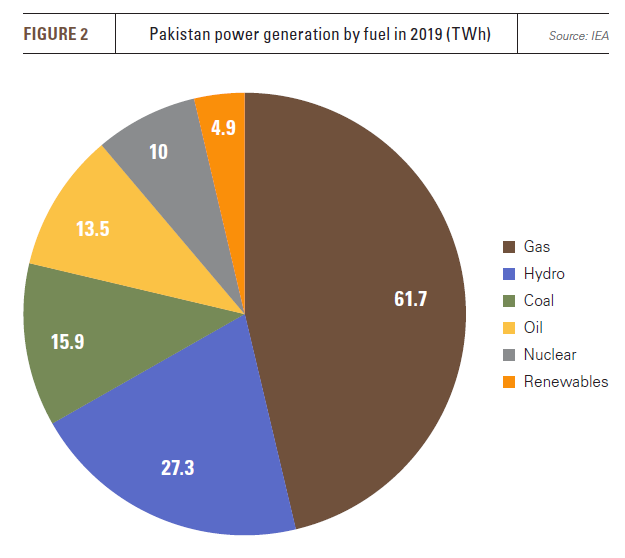

Output in 2019 was a relatively modest 10 TWh (Figure 2). This will increase in the near term since the 1 GW Kanupp-2 reactor at Karachi entered commercial operation in May 2021, according to the World Nuclear Association. In addition, a 1.1-GW reactor is under construction with Chinese assistance for operation from late 2022, and a similar-sized facility is at an advanced stage of development.

However, the 2014 projection by the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission that capacity would reach 8.9 GW in 2030 seems unrealistic, in part because of the financial, technical and other constraints imposed by nuclear proliferation rules.

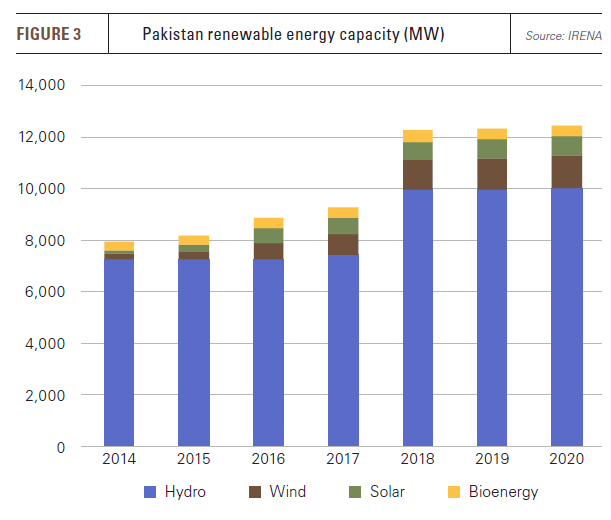

Renewable energy might appear a good option given the potential resources but has only increased slowly in Pakistan compared with many Asian countries. In 2020, renewable energy produced only 5 TWh, with wind turbines generating 2.7 TWh from 1.2 GW of capacity, while solar PV facilities produced 1.7 TWh from 0.7 GW of capacity (Figure 3).

Hydroelectric output is more substantial, accounting for over 30% of total electricity output in the period from July 2019 to April 2020, according to the Pakistan Economic Survey. Output has increased with the completion of new dams but varies depending on the weather and competing claims for water supplies, both within and outside the country. In the latter respect, those hydro facilities which use water from rivers flowing from India can also be affected by political factors.

Coal was at one stage seen as a major contributor to energy supply, based on the low quality but substantial resources in Thar and elsewhere in the country. However, development of the resources and associated generating plants has proceeded slowly. In the mid-2010s, it was planned that almost 8 GW of coal-fired capacity would be operational by 2019 on the basis of Chinese state financing. But few of the projects have made progress, meaning coal-fired output of 15.9 TWh accounted for only 12% of total generation in 2019, according to the International Energy Agency.

The limited alternatives mean the power sector is to a large extent dependent on gas, which in 2019 accounted for 46% of total electricity output. It is also the largest source of energy in the industrial and other sectors. In 2020, gas accounted for almost 43% of all primary energy.

Pipe dreams

Limited domestic gas and other energy supplies mean gas imports already form a key part of national energy supply and will continue to do so for years to come. But this does not necessarily mean LNG imports. Piped imports could in theory supply a large part of Pakistan’s imported gas requirements, for example via the Iran-Pakistan (IP) and Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) lines. But both projects are problematic.

Iran and Pakistan signed a contract in 2008 for the IP line, with Iranian officials saying in 2015 that the 900-km section in Iran had been completed. But, in January 2017, the head of the National Iranian Gas Company said the project could be shelved because of extensive delays, and, in late 2021, Pakistan’s President Arif Alvi acknowledged that negotiations had completely stalled.

The 1,800-km TAPI pipeline from the Galkynysh field in Turkmenistan to the Indian border is the biggest project currently under construction, with a capacity of 33bn m3/yr. However, it has been dogged by security concerns and financing issues since its inception in 1990. The Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan has not improved the situation. In November, Pakistan’s minister for economic affairs, Omar Ayub Khan, said work on TAPI had been suspended indefinitely because of the situation in Afghanistan.

LNG capacity

All of which puts the onus squarely on LNG. Pakistan’s first terminal, a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU), entered service at Port Qasim in March 2015. It was installed by the US’s Excelerate Energy for Engro Elengy Terminal Ltd (EETL), now a joint venture between the local Engro Energy and the Netherlands’ Royal Vopak.

In 2020, Excelerate and EETL agreed to expand the facility’s storage capacity from 150,900 m3 to 173,400 m3 and increase its send-out capacity. The International Gas Union put the facility’s import capacity at 4.2mn mt/yr in 2021, up from 3.8mn mt/yr formerly.

A second terminal entered service in mid-2017 at Port Qasim following a competitive tender. The 170,000-m3 FSRU was installed by Singapore’s BW for the PGP Consortium, which includes the local Pakistan GasPort Limited and Fauji Oil Terminal and Distribution Company. Import capacity is 5.7mn mt/yr.

At least three more terminals were proposed in the mid-2010s, and, in February 2017, the state-run Pakistan LNG Limited projected that, by 2022, LNG imports could reach 30mn mt. However, imports are under a third of that, with the country’s regasification capacity still comprising only the two FSRUs, totalling 9.9mn mt/yr.

Positive signs

After a series of false starts there are positive signs. Two onshore projects are at an advanced stage of development at Port Qasim, with both intended to operate on a merchant basis. A $500-600mn project is being developed through Energas Terminal Ltd by Engro and Royal Vopak, with local media reports saying in late 2021 that Qatar Energy might also invest. The second project is being developed by Japan’s Mitsubishi through Tabeer Energy.

The two projects received construction licences from the Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority in April 2021. However, both developers have complained that bureaucracy and obstruction from incumbent players, especially regarding access to pipelines, has prevented them from taking final investment decisions.

The two projects received construction licences from the Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority in April 2021. However, both developers have complained that bureaucracy and obstruction from incumbent players, especially regarding access to pipelines, has prevented them from taking final investment decisions.

The slow development of the pipelines needed to move gas across the country has been an issue for many years. This is especially true of the 1,040-km, 12.4bn m3/yr Pakistan Stream Gas Pipeline, formerly known as the North-South Gas Pipeline, which is being developed through a 74/26 joint venture with Russia and will seek finance from Russian state banks backed by a sovereign guarantee. It would transport gas from Karachi to Punjab, and could be connected to the proposed TAPI pipeline at Multan. Operation is optimistically planned from 2023.

Uncertain prospects

However, the current surge in LNG prices has raised deep concerns in Pakistan about use of the fuel, not least after the country’s main term suppliers, Gunvor and Eni, declared force majeure on some deliveries. With spot purchases also hard to get or prohibitively expensive, severe gas shortages are occurring and a reversion to the use of oil in power generation and industry is being promoted by some government officials.

The Oil Companies Advisory Council reported in September that Pakistan consumed 870,000 mt of fuel oil in July and August 2021, up from 550,000 mt in the same period in 2020.

Eschewing LNG is not likely to be a long-term trend, but high prices in 2021 could see Pakistan’s LNG industry reverting to past practices. Some new LNG terminals could be built by deep-pocketed and well-connected local investors.

While the government is ostensibly committed to opening the gas sector to competition, in some cases projects could be based on long-term, take-or-pay offtake arrangements and sovereign guarantees. The state is also likely to maintain significant involvement in the sector through the ownership of pipeline infrastructure built on the basis of government-to-government finance and contracts.

Indeed, state involvement could spill over into the provision of LNG capacity and supply. In late 2021, economic minister Omar Ayub Khan said Russia could fund, build and supply new LNG terminals. Given Pakistan’s long-standing reliance on Russian, Chinese and multilateral-based investment, this is not surprising. And it could in fact mean that Pakistan’s demand for LNG – and impact on the international market – could be greater than otherwise through a higher take, albeit based mainly on supplies bought through long-term contracts rather than the spot market.