[NGW Magazine] Greece and EU Security

NGW interviewed Professor Yannis Maniatis, a former energy minister of Greece, about energy security in Europe and around the world. Malicious states or individuals can put at risk the physical supply of energy and operators need to be more vigilant.

.png)

Yannis Maniatis believes we are living in turbulent times and the old ‘business as usual’ approach is not adequate to meet the challenges Europe is facing.

The need for a single European foreign and defence policy, coupled with a centralised energy policy, is now more than ever necessary, because energy security is important for all economies. As he sees it, energy in the future will be decentralised, lower-carbon and digitalised.

Greece’s contribution starts with shipping, he said. In the global supply chain of energy flows, Greek shipping plays a very important role, representing a fifth of total tonnage and half the total in the EU. More specifically Greek owners control 30% of the world crude oil tanker fleet, a sixth of the world’s chemical and products tanker fleet; and are a close second behind Japan in terms of LNG vessels. In relation to energy, Greece’s infrastructure requires investment of at least €15bn, which will also enhance the country’s ailing economy. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) every €1 ($1.2) spent on energy infrastructure, gross domestic product is further increased by €0.8.

Greece fully supports the EU approach to energy security and promoted major projects for energy supply diversification, namely:

1. The TransAdriatic Pipeline (TAP)

Greece worked closely with the promoters to conclude the permits and complex host government agreement and ensured that the project will be developed on time by 2020. TAP‘s initial capacity of 10bn m³/yr amounts to the energy demand of some 7mn households in Europe. In its second phase, TAP can deliver 20bn m³/yr. TAP's realisation is a milestone – and a triumph – for EU’s approach to energy security.

2. Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (IGB)

The IGB is not just a local pipeline. Its importance stretches beyond Greece and Bulgaria. The IGB will connect with TAP, meaning southeast Europe gains access to the Southern Corridor, he said. In addition to Caspian gas, the IGB will deliver to the region gas from LNG terminals in Greece, from Revythousa and the planned floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) in Alexandroupolis.

3. The Vertical Corridor

This consists of linking up existing infrastructure with planned interconnectors to enable diversified sources to reach throughout the broader region – up to Ukraine. The starting point is the IGB, which really constitutes the cornerstone of the strategy.

4. East Mediterranean

Greece promoted the EastMed gas pipeline connecting off-shore gas resources to European markets via Cyprus and Greece. This is a most important project, primarily because it introduces a new source and a completely new corridor. There are other options for bringing Mediterranean gas to Europe, which should be considered, including LNG terminals in Egypt.

There is also discussion on a pipeline through Turkey. From an energy security perspective this is the least satisfying option, because – even leaving politics aside – it does not provide a new route for the EU. Turkey is already the transit route for Caspian gas. The EU must ensure that more and new transit routes are created to ensure diversification of supplies and reduce dependency on any one country.

5. Greek oilfields

It should be understood that Greek oilfields, along with those off Cyprus and Israel, are the new major source of Europe's supply of natural gas. I usually refer to the eastern Mediterranean area as Europe's new energy Eldorado.

_f498x534_1525291006.jpg)

Map: Greek gas projects in progress/planning (Credit: Entsog)

Through these projects Greece is becoming an important gas corridor to Europe. The privatisation of Desfa, completed April 19, will also contribute to this through its international ownership.

The consortium of Snam, Fluxys and Enagas offers synergies between the Desfa network and the Albanian gas grid, which Snam has undertaken to develop; TAP, where Snam has 20%, and in the future the "vertical axis" between Bulgaria and Romania-Serbia-Hungary (BRUA), ends at the Baumgarten hub in Austria.*

It is certain that in the Energy Union, the vision of a large single, European energy market with security of supply, faces major challenges. As a major energy importer, Europe’s energy security is threatened by political unrest in the key production regions, notably those of the Middle East.

This threat should be addressed primarily through diversification and by policies promoting indigenous production of hydrocarbons, energy efficiency and renewables. Greece offers such opportunities to Europe as an important gas corridor, but also through the development of its hydrocarbon fields which are promising to be gas-rich.

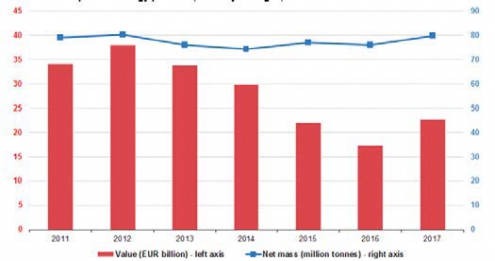

We all agree that dependence on few sources increases risks to un-acceptable levels. More diversification also increases competition and leads to lower prices. Last year, despite EU efforts at source diversification, Gazprom reported record exports to Europe for the second year in a row. In fact exports grew 8.1%, to a record level of about 195bn [Russian] m³. As a net importer, the EU has a massive energy bill. According to Eurostat, the average monthly value of imports in energy products last year was €22.7bn. Reliance on imports makes Europe vulnerable to volatile markets, especially oil.

Figure 1: EU energy imports - monthly averages

Source: Eurostat

In 2017 the monthly bill actually rose as much as 31% in comparison to 2016, even though imported quantities changed little (Figure 1). Greece is ensuring its gas diversification through the gas projects shown, but also through the upgrade of the LNG import facilities at Revythousa, to be commissioned by September 2018, and the FSRU at Alexandroupolis.

The latter project is progressing, with final investment decision expected later this year and operations scheduled to start 2020.

This has acquired new significance as it forms an important component of the Greek gas corridor to Europe. It is also becoming of pivotal importance for Europe’s energy security and gas diversification efforts.

With the expansion of the Revythousa LNG terminal and commissioning of TAP, from 2020 onwards Greece will not be affected by any disruption in gas supplies, for example through Ukraine.

Asked whether an energy security strategy primarily address the broader foreign policy issue concerns, or instead focus on ensuring the most secure routes for supplies, he said: "These issues are naturally complex. We cannot be absolute in our assessments. Energy can produce conflicts and peace. The EU’s energy security approach should focus on its interdependence with energy producers."

Especially in the case of gas, the dependence of exporters is at least equal to the dependence on imports. The fact that the EU is by far the largest gas import market, this provides it with significant political leverage. We have also to face non-state threats to energy security.

Cyber-attacks, terrorism and piracy, are key examples of non-state threats to energy security.

Systematic assaults

According to Nato, in the past years, terrorists and insurgents made about 500 attacks on energy-related targets in an average year. This included the bombing of gas and oil pipelines, attacks on fuel trucks, killing and kidnapping associated personnel, and disrupting electrical power systems.

Most of these attacks are clustered in a few specific regions, such as west Africa. The most popular targets are pipelines, often in some of the most volatile areas in the world, like Iraq and Libya.

Terrorism at sea, piracy and armed robbery, is an area of increasing concern. Today, over 60% of the world’s oil and almost all of its LNG is shipped on 3,500 tankers through a small number of ‘chokepoints’ – straits and channels narrow enough to be blocked, and vulnerable to piracy and terrorism.

Looking at cyber-attacks, this is not just a concept. These incidents are increasing and pose a real threat. All these activities can disrupt the critical infrastructure that the European economy depends on. According to the European Commission, the economic impact of cybercrime rose fivefold from 2013 to 2017, and could quadruple by 2019.

As someone said to me, one of the main risks of cyber-attacks is to think they don’t exist. It’s incredible, really! A large-scale cyber-attack on civilian critical infrastructure could cause chaos by disrupting the flow of electricity, money, communications, fuel and water. They can potentially be a disaster for the environment.

For example, dynamic positioning systems of offshore oil and gas rigs could in theory be hacked. This would cause spills and environmental disasters akin to the Deepwater Horizon accident.

So addressing cyber risks in the energy sector is critical for energy security, but also vital for a resilient state and economy. The gravity of the problem is demonstrated by the fact that last October, the FBI officially issued a warning to US owners of critical infrastructure. According to experts in Congress, incidents so far are just the beginning.

At the same time, rogue states are increasingly meeting their geopolitical goals not only through traditional tools like military force, but also through more discreet cyber tools, including interfering in internal democratic processes and disrupting critical infrastructure.

The use of cyberspace as a domain of warfare, either solely or as part of an hybrid approach, is now widely acknowledged. Unless we substantially improve our cyber-security, the risk will increase in line with digital transformation.

Tens of billions of "Internet of Things" devices are expected to be connected to the internet by 2020, but cyber-security is not yet prioritised in their design. A failure to protect the devices which will control our power grids could have devastating consequences.

The EU – to its credit – is taking important action to address non-state security threats of energy security. The NIS Directive, on security of network and information systems, was adopted in 2016 and should be implemented across the EU by May 2018.

It is a step in the right direction because it brings together sectoral action, for example the EU’s Cyber strategy, the Energy Security strategy, identification of critical infrastructure and the EU Maritime Security strategy.

Having said all the above, let me express my hope that Europe will keep being the more ambitious international entity on energy security and protection of the environment, as it drives towards a low carbon economy.

Charles Ellinas

*Separately from the interview, Snam confirmed its keenness on the acquisition, looking forward to the strategic benefits from the synergies with these projects - CE..