Which ship engine should a new ship owner shoot for? [LNG Condensed]

Which ship engine should a new ship owner shoot for? Sounds like a bit of a tongue twister, but it is a highly relevant question for the shipping industry given the uncertainty over future air pollutant and greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) regulation. Ships can be in service for 30 years, so choosing the right engine now – one that is effectively future proof and economical – will avoid costly retrofits later or even worse obsolescence.

Which ship engine should a new ship owner shoot for? Sounds like a bit of a tongue twister, but it is a highly relevant question for the shipping industry given the uncertainty over future air pollutant and greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) regulation. Ships can be in service for 30 years, so choosing the right engine now – one that is effectively future proof and economical – will avoid costly retrofits later or even worse obsolescence.

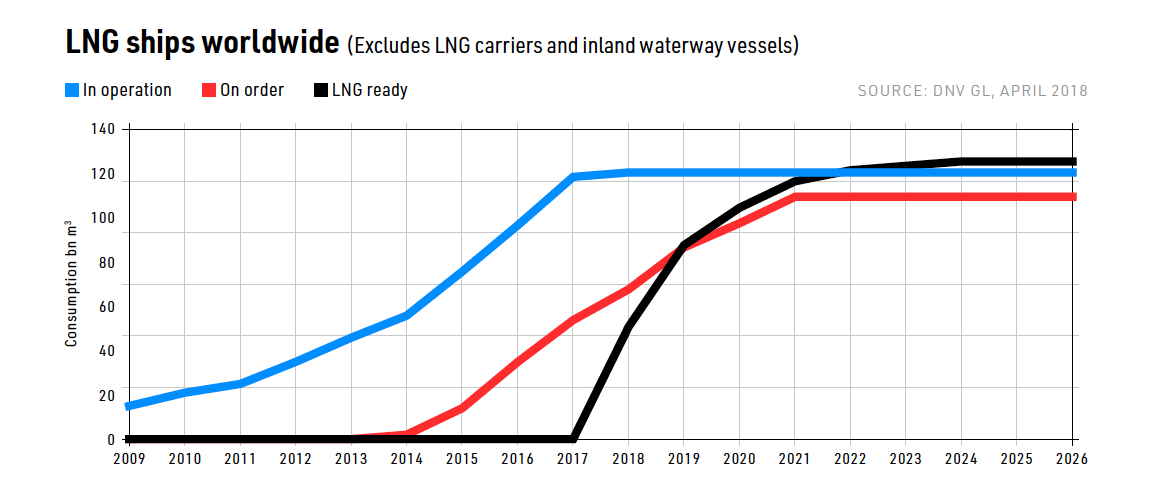

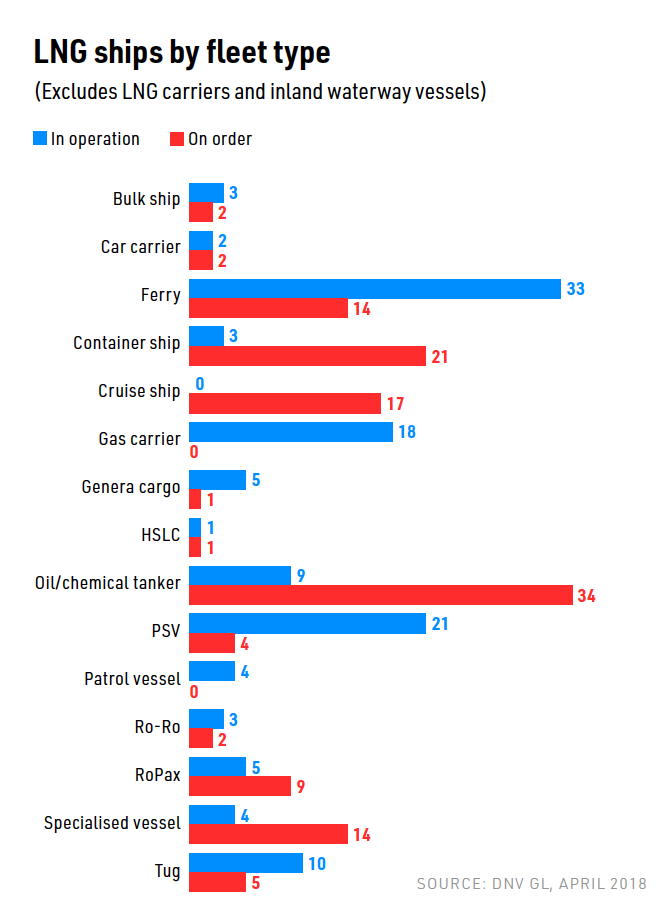

Which engines are chosen now and in the coming decades will also determine demand for different types of shipping fuel, making it a key question for the oil and gas industry. In particular, LNG developers see both sea and road transport as potential new markets for gas and are developing bunkering facilities in and around existing LNG terminals, particularly in Europe.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

However, a recent report by Imperial College London’s Sustainable Gas Institute (SGI) – Can Natural Gas Reduce Emissions from Transport? -- has cast doubt over the emissions savings that gas-to-transport supply chains can deliver, as well as challenging some of the claims made about reduced nitrogen oxides emissions.

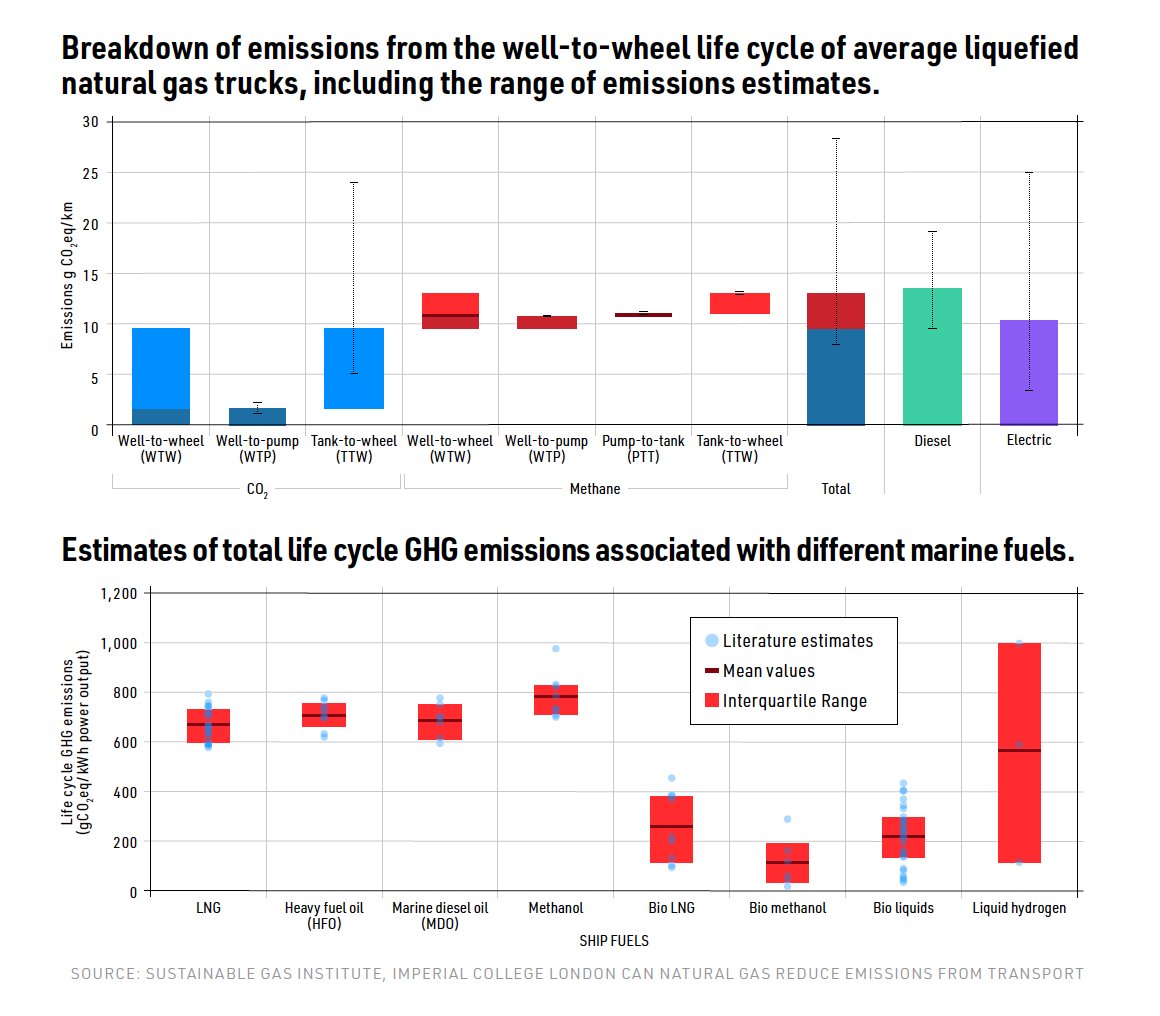

In particular, for LNG supply chains, the energy used in liquefaction is a major issue, as are methane emissions all the way down the supply chain to the engine, where incomplete combustion can result in methane slips. Methane as a GHG is about 34 times more potent than carbon dioxide. The report finds that some LNG engines both for land and sea transport, depending on their usage, can in fact be worse in terms of overall emissions than diesel engines.

The report does say that significant emissions savings can be made from LNG use in shipping, but not enough to meet the targets set by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO). Equally, however, while it promotes sustainable fuels as an option for the deep decarbonisation of transport necessary by 2050, it admits the difficulties in producing these in sufficient quantities to meet the huge demands of the global transport market. Other options for deep decarbonisation – efficiency, hydrogen and wind-assisted vessels for example – also have their challenges.

The report thus raises important practical and philosophical questions for policy makers and industry participants alike:

- If gas in transport is not the ultimate solution should it be ignored in the interim when it can address a significant part of the problem, particularly when other options are not yet commercially or technologically available?

- Does characterising gas in transport as an imperfect, interim solution risk the loss of policy support – in other words would governmental support for gas crowd out the longer-term solutions than can deliver deep transport decarbonisation?

- Would a failure to promote gas in transport undermine other benefits of the fuel, which in the European context centre around the security of supply provided by LNG imports, given the region’s growing dependence on gas and the limited number of pipeline importers?

It is notable that support for East European LNG projects, for example in Poland and Lithuania, has been provided largely on security of supply rather than climate change grounds. Equally it could be argued that the IMO’s emissions reductions targets cannot be met without the growth of gas in transport, particularly given the paucity of immediately available alternatives.

What is crystal clear, however, is that the gas industry, if it is to have any chance of being a short or long-term part of the solution, must deliver best practice ruthlessly from the beginning to the end of the supply chain.

Shipping dilemmas

The shipping industry already faces a reduction in the sulphur content of bunker fuel from 3.5% to 0.5% globally, a measure which comes into force from January 1, 2020. In addition, ships have to meet the strictures of the Ballast Wastewater Management Convention, which came into force on September 8, 2017. This calls for the gradual installation of compliant ballast waste water systems.

Given the impetus behind climate change mitigation, it is near certain that maritime transportation will be the target of future regulation aimed not just at water and air pollution but carbon dioxide emissions. Shipping accounted for 2.6% of global carbon dioxide emissions in 2015. The IMO adopted in April 2018 a target of reducing total GHG emissions from shipping by at least 50% below 2008 levels by 2050.

However, it also forecasts that emissions from shipping could grow by anywhere between 50% and 250% by 2050 as a result of increased demand for seaborne freight.

The expected increase in shipping activity clearly runs counter to the IMO’s emissions reductions target, which in turn suggests the recent curbs on ballast water and sulphur are just the beginning. The only way the IMO’s reduction in emissions can be achieved, while the fleet itself expands, is a huge reduction in the carbon intensity of shipping. That is the dilemma faced by new ship builders keen not to fall foul of future regulation.

Natural gas

A switch from oil products such as heavy fuel oil (HFO) or marine diesel oil (MDO) to natural gas would seem like an obvious option given the lower carbon and sulphur content of natural gas/LNG, but the SGI’s report concludes that natural gas will not be enough to deliver the emissions reductions required by the IMO.

The study reveals that while LNG in shipping is clearly beneficial in the reduction of air pollutants such as particulates, nitrogen oxides (in some cases) and sulphur oxides, the savings in GHGs on a full life cycle basis are not as great as might be expected.

The study estimates that LNG in shipping can reduce GHG emissions by 10% relative to oil products such as HFO when comparing the best cases for both fuels. The figure for road transport is a reduction of 16%. These are significant gains, but in the case of shipping it is nowhere near enough to meet the IMO’s 2050 target, which will need to be met by ships built from 2020 on.

The SGI report estimates that supply chain emissions account for 23%-27% of natural gas’ shipping emissions, but that methane slips can add a further 2%-20%. Methane slips largely reflect incomplete combustion, so that the emissions from a natural gas or LNG-fuelled engine comprise both methane and carbon dioxide. Given the potency of methane as a GHG it doesn’t take a lot of slippage to undermine the beneficial effects of burning a lower carbon fuel.

The report says: “At worst, natural gas fuelled trucks and ships may have lifecycle emissions exceeding current incumbent diesel trucks and heavy fuel oil ships. Dual fuel trucks in urban driving cycles or ships using low pressure dual fuel or lean burn engines are most likely to exhibit these high emissions.”

There also appears to be a trade-off with some engine types between nitrogen oxides and methane slips. Higher combustion temperatures produce more complete combustion but also more nitrogen oxides.

Such findings have negative implications for the natural gas industry because if LNG in shipping is not seen as part of the solution it will not find policy support. Indeed, detractors argue that support for LNG bunkering infrastructure will in fact lock in gas use in shipping long term, undermining other more permanent solutions.

However, the report does underline that with the right engines and best practices, natural gas in transport can deliver significant emissions savings and reductions in air pollutants – and can do so more immediately than the longer-term alternatives.

Report scenarios

The SGI report outlines a number of scenarios, the first of which envisages a gradual transition in shipping from HFO to MDO and then to gas-fuelled vessels, split evenly between all types of gas engine technologies, driven primarily by regulation rather than cost.

The result is a 35% reduction in marine transport emissions from a 2015 baseline. Methane emissions rise from 0.5% of emissions to 6.7% in 2050 as a result of the growth of gas-fuelled engines. In this gas-dominated scenario, emissions reductions exceed the 2050 target by 15% against 2008 levels. It should be noted that this is not the best possible case for gas as it splits gas engine adoption across all technologies rather than the best performing on an emissions basis.

A second scenario involves an extended EEDI (Energy Efficiency Design Index) requirement for new ships to meet a 40% emissions reduction after 2030. The EEDI was made mandatory by the IMO for new ships in 2011 and requires a minimum energy efficiency level per capacity mile for different ships depending on type and size. The EEDI is incrementally tightened every five years from 2013.

This scenario is challenging as a 40% EEDI by 2030 would mean efficiency improvements at a rate over twice the historic average, the report says. It also sees the focus on carbon dioxide emissions failing to address the growth of methane emissions resulting from increased gas engine use. In terms of overall emissions by 2050, the results are only marginally better than the first scenario.

In its third scenario, hydrogen-fuelled ships start to have an impact, but not until 2040. This results in a carbon dioxide emissions reduction in 2050 below the 50% reduction target, but only if the rise in methane emissions is ignored.

Low carbon fuels

It is clear, as the report states, that meeting targeted emissions reductions from transport is challenging and that an ‘all of the above’ strategy is required. Gas may be part of the solution, but should not crowd out development of other lower GHG technologies for deployment later in the 2015-2050 timeframe.

The threat for gas-fuelled shipping is that although carbon dioxide emissions are cut, it will be penalised for the forecast offsetting rise in methane emissions.

The assumption that EEDI measures have little impact on the increase in methane emissions is perhaps questionable as both methane and carbon dioxide emissions should be proportionate to fuel use, which will fall per mile travelled as a result of increased efficiency.

The long-term solution, however, is lower carbon fuels than gas – biofuels to the extent they can be produced, given land and food effects, as well competition from the aviation sector, which appears to have even fewer options than land or sea transport; electrification where possible, for example in short-haul ferry operations; hydrogen, where it can be produced sustainably; and investment in efficiency, for example hull coatings and design and new wind and solar-assisted ships.

But in any scenario gas appears to play a key, if imperfect role. The onus must be on promoting the very best practices in supply chain management, engine type and use, alongside all of the other measures.

So … which engine?

What then is the answer to the question -- which ship engine should a new ship-owner shoot for?

Dr Tristan Smith of University College London’s Energy Institute gave this advice: “design your ship now to be flexible in operation”. Buying an LNG-only engine, he said, locks the ship owner into only one ship of the future, potentially at high capital cost. Be LNG-ready, but retain the option for biofuels, potentially ammonia or hydrogen, or retrofitting scrubbers for fuel oil or diesel.

Not perhaps the best advice in climate terms given the SGI’s downbeat assessment of some duel fuel engines, but in the face of policy and technological uncertainty, there is clearly value in flexibility.

_f193x247_1552386214.jpg) LNG Condensed brings you independent analysis of the LNG world's rapidly evolving markets.

LNG Condensed brings you independent analysis of the LNG world's rapidly evolving markets.

Covering the length of the LNG value chain and the breadth of this global industry, it will inform, provoke and enrich your decision making. Published monthly, LNG Condensed provides original content on industry developments by the leading editorial team from Natural Gas World.

LNG Condensed is your magazine for the fuel of the future. Sign Up Free below:

Volume 1, Issue 2 - February 2019

> Japan: future uncertainty, but potential upside

> Which ship engine should a new ship owner shoot for?

> Argentina to join LNG production club

> Poland’s 2040 energy plan provides key role for LNG

> LNG Canada — a game changer for Canada’s gas industry

> Conference Report: EGC Vienna

and more!

Sign up now to receive LNG Condensed monthly FREE