Weighing up options for Guyana-Suriname gas [Gas in Transition]

Guyana’s plans for the development of offshore hydrocarbon reserves encompass associated gas as well as crude oil.

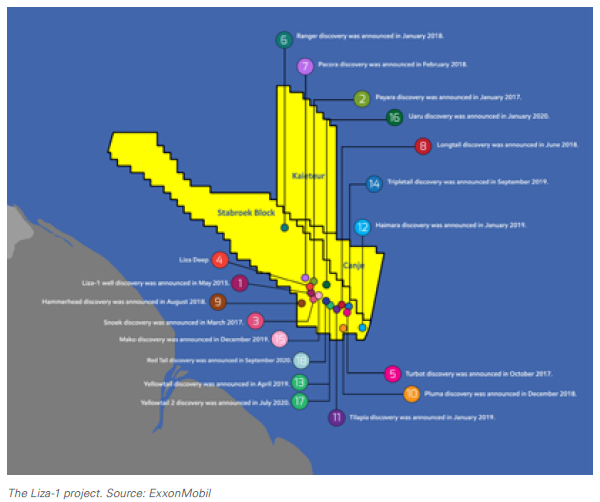

More specifically, the US major ExxonMobil has reached an agreement with the government of Guyana that provides for pumping associated gas from Liza-1 and other sections of the Stabroek block to shore for various uses, including but not limited to power generation. Officials in Georgetown have said they hope gas from offshore oilfields will help transform the Guyanese economy – partly by enabling the production of cheap electricity, partly by serving as fuel for large industrial and manufacturing facilities and partly by serving as feedstock for petrochemical and chemical production.

There have also been proposals for using Guyana’s gas to benefit the region at large. In August 2021, for instance, Guyanese president Irfaan Ali and his Surinamese counterpart Chandrikapersad Santokhi began talking about setting up a regional energy network that would also incorporate French Guiana and northern Brazil. The idea has attracted interest from Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, but the parties postponed further talks in January 2022 and have yet to take up the matter again.

Meanwhile, a third gas-to-power (GTP) option has emerged. It does not resemble the agreement between Georgetown and ExxonMobil, in that it’s not tied to a specific project, and it isn’t much like the proposed regional energy network, in that it’s being championed by private-sector investors rather than government officials. It also appears to be changing in response to current market conditions.

First version: Offshore gas hub

The project in question has evolved quickly, and it may not even have reached its final form yet.

The initial version envisioned the establishment of a gas hub – that is, a facility capable of receiving associated gas from oilfields off the coast of both Guyana and Suriname and then directing it either to shore for local use or to an offshore liquefaction plant for export as LNG. Phoenix Development Co (PDC), a Houston-based group set up by investors from multiple countries, appears to have begun pursuing this plan early last year, saying it expected to spend $2bn.

This version of the project tied in with PDC’s other projects – namely, the Deep-Water Port and Special Economic Zone (SEZ) facilities that the company is slated to build in cooperation with Havenbeheer Suriname (HBS), the port authority of Paramaribo. Indeed, PDC saw the hub as essential for the DWP and SEZ, both of which will be constructed along Suriname’s western coast, noting that it would supply both with gas, thereby providing them with the affordable and reliable access to fuel and energy they need to attract high-value tenants.

In mid-February of 2022, PDC said in a statement that it had teamed up with Make a Difference Ventures (MAD), a clean energy investment platform based in Idaho, to award a contract to Dallas-based Schwob Energy Services (SES) for front-end engineering and design (FEED) services on the facility. It did not reveal the value of the contract, but it did report that SES would be drawing up plans for construction of the hub. It also stated that the facility would be built in the deepwater section of Suriname’s offshore zone and would include delivery, storage and off-loading facilities, plus a gas liquefaction plant and pipeline connections.

Additionally, it said the hub could serve as a destination for associated gas from offshore oilfields in the Guyana-Suriname basin. The facility would move some of this gas into pipelines for delivery to shore, while sending the remaining volumes to the gas liquefaction plant for processing into LNG, which could then be transferred to tankers for export, it explained. This LNG plant would have a single production train with a capacity of 4mn metric tons/year, it said.

In its February statement, PDC declared that the establishment of this gas hub and LNG plant would help reduce the environmental impact of oil development in the Guyana-Suriname basin. Providing a destination for associated gas from local oilfields ensures that the gas can be used rather than flared, it explained.

Additionally, PDC is pursuing more ambitious environmental goals. The company also has drawn up plans with MAD to use some of the gas it handles to produce electricity to operate the LNG plant as part of an overarching effort to bring its net carbon dioxide emissions down to zero. This net-zero initiative also envisions the establishment of units for the production, storage and loading of liquid hydrogen as well as LNG. As such, it gives Suriname a way to participate in the energy transition, it said.

Reasons to build

This is an ambitious undertaking. It also has certain attractions.

For one, it will create an additional revenue stream. Both Guyana and Suriname have discovered oil offshore; Guyana began exporting its production to the world market shortly after ExxonMobil brought the Liza-1 field on stream in December 2019, and Suriname intends to do the same once France’s TotalEnergies starts development at Block 58. Therefore, both can expect to earn money from oil exports. The gas hub project would allow them to earn money from gas exports as well.

Secondly, it will guarantee gas supplies to onshore development areas. As mentioned above, PDC expects to have an easier time attracting high-value tenants to both the DWP and SEZ if it can guarantee reliable supplies of low-cost fuel and energy.

Thirdly, there is broad support for economic development within Suriname. Beyond the DWP and SEZ, the hub will also be able to deliver gas for use at other onshore facilities in Suriname. It can serve as an analogue of Guyana’s GTP project and deliver some of the same benefits, serving as feedstock for thermal power plants (TPPs) and petrochemical production and as fuel for large industrial and manufacturing facilities.

Second version: Onshore mid-size LNG plant

PDC has pointed out, though, that there are also geopolitical reasons to promote the project. In a separate statement dated March 27, it alluded to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, saying that there was now more interest than ever in new gas supply options.

“In contrast to the period in which the cooperation agreement [between HBS and PDC] was prepared and signed, the global situation has now changed dramatically. Due to the acute energy crises in the global liquefied natural gas markets, with record prices in Europe and Asia, conditions are currently favourable for the accelerated development of the Deep Water Port and Special Economic Zone in the west of Suriname,” it commented.

Under these circumstances, it noted, Suriname’s president has stated his support for the project and pledged to provide PDC with whatever support is needed.

This support may have to take a different form than previously expected. PDC indicated in late March that it had changed course. Specifically, it said it had joined forces with MAD to set up a new entity called Firebird LNG to establish a new solution for gas producers in the Guyana-Suriname basin. It described this solution as “an open-access gas pipeline, with equal treatment for producers on both sides of the border to deliver natural gas to shore for liquefaction.”

As of press time, it was not clear how this shift from offshore gas hub to onshore LNG plant might affect the project. PCD has not said whether it still expects the final price tag to be $2bn, whether the LNG plant will still have a production capacity of 4mn mt/yr, whether it will have to renegotiate the terms of the FEED services contract with SES or whether it foresees any other changes.

Additionally, PDC has not talked about where it expects to find feedstock for the plant – and this could prove to be a crucial point, given that Phoenix LNG will not be tied into any upstream projects. It has also not spoken about Guyana’s response to the project. This could be a problem, as the company is hoping to secure gas from Guyanese deposits as well as Surinamese fields, but the exact scope of that problem will depend on the size of Suriname’s gas reserves, which is not yet known.

In any event, there are still many questions about this project. Firebird LNG has the potential to make a major difference in the regional economy – and in the evolution of the local oil and gas industry. However, PDC and its partner MAD have yet to provide a full explanation of exactly what they plan to do in this emerging hydrocarbon province – and without that, it will remain difficult to provide an objective evaluation of their plans.