[NGW Magazine] Fierce rivalries

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 12

By Charles Ellinas

Reality rarely obliges government forecasters, and Statoil’s analysis suggests the armies of planners working on the Paris Agreement will be disappointed.

In its annual, fact-based, report Energy Perspectives 2017, Norwegian oil and gas major Statoil for the first time went beyond the near future and considered three scenarios covering the period to 2050:

• Reform, which proceeds from current macroeconomic and energy market trends and strict adherence to nationally determined contributions (NDCs) in the Paris agreement to market-based solutions that drive and deliver energy-efficient and low-carbon technologies

• Renewal is about a technically possible, but very challenging, pathway to energy-related CO2 emissions consistent with a 66% probability of limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius (2degC) by 2100.

• Rivalry looks the most recognizable scenario, however – a world characterised by mounting distrust in conventional politics and policy-making, populism, protectionism and geopolitical conflict, and where focus on security of supply and other priorities overshadow global climate targets.

The choice of the three scenarios is in common with previous Statoil reports, reflecting the considerable uncertainties associated with long-term developments in global energy markets. In preparing this report, Statoil sourced data from before this year from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Not surprisingly, in its key scenario Renewal, Statoil concludes that immediate action is needed to transform the global energy system if the 2degC target is to be achieved. This is similar to the conclusion reached by IEA and the International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena) in their joint report on The perspectives for the energy transition, published earlier this year, that achieving 2degC requires immediate, drastic, action by all countries globally and on a grand scale.

The three scenarios

Average global economic growth is estimated to range from 1.9% to 2.6%/yr, with global GDP growing by 2050 between 1.9 and 2.6 times that of the level in 2014.

Global economic growth is led by growing populations, bigger middle classes and emerging economies gradually catching up, with demand for products and services that require energy increasing.

Reform is characterised by national policy-making, reflecting national and private economic self-interest, influenced by international policies.

Market forces coexist with climate policies, with the Paris agreement playing a role and most countries delivering their NDCs. Global GDP grows but at a slower rate than up to now – by 2050 it is 2.5 times the global GDP at 2014.

In Reform there are significant improvements in energy efficiency, with average annual energy intensity declining by 1.9%, which is more than double the performance over the last 25 years.

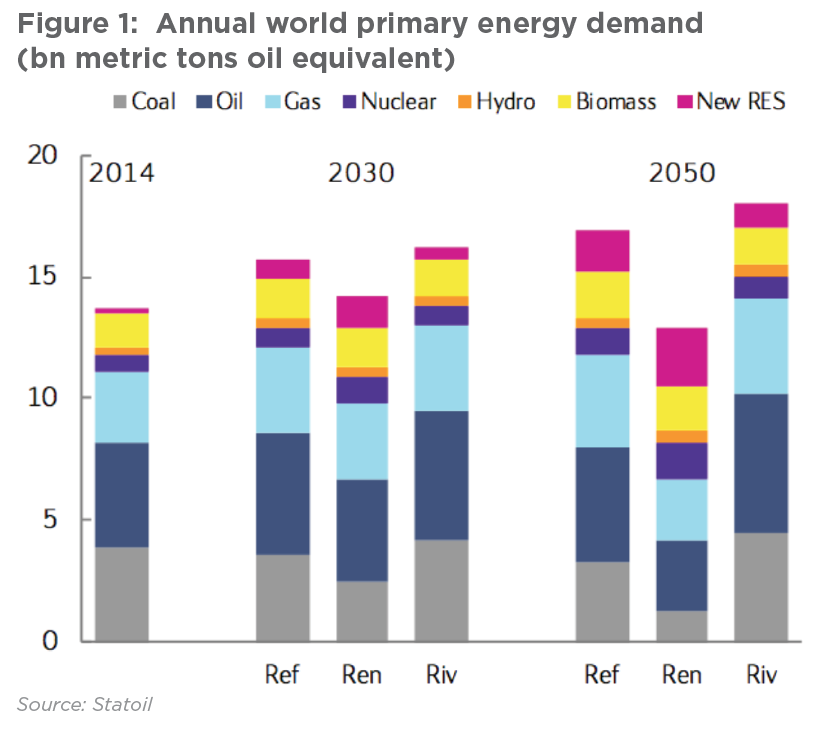

But in this scenario continued growth in global GDP outweighs the effects of a strong decline in energy intensity, which results in increasing total primary energy demand. By 2050 it grows to levels 23% higher than in 2014 (figure 1).

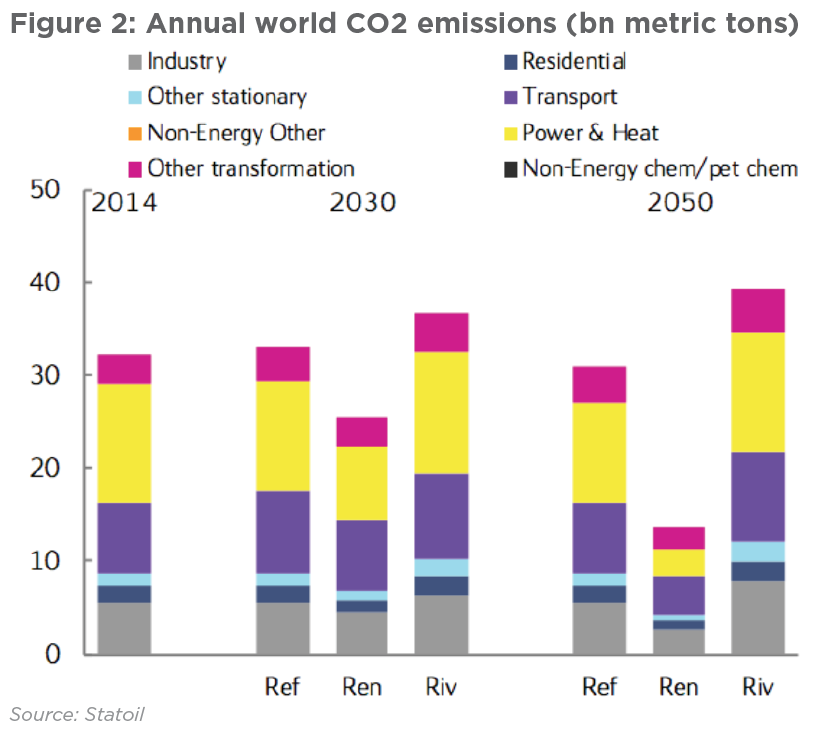

This leaves annual CO2 emissions largely unchanged from 2014 levels (figure 2). As a result accumulated emissions by 2050 are much higher than the level required to stay within the 2degC target.

This means that in terms of achieving the 2degC target Reform is not a sustainable scenario in the long run, leaving a wide gap when compared to the goals of the Paris agreement.

Renewal offers a pathway to achieve this energy sustainability. In this scenario, it is geopolitical co-operation, not competition, that drives policy, with all countries jointly tightening CO2 emission reduction commitments consistent with the 2degC target.

Renewal is characterised by stable global policy and regulatory frameworks, including high carbon pricing which incentivises the development and deployment of large-scale carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Energy efficiency is boosted across developed and emerging economies, with investments and technology transfers rapidly generating greater buy-in for greener forms of energy. By 2050 these lead to global GDP growing slightly above the Reform scenario, reaching 2.6 times the global GDP at 2014.

They also result in an unprecedented pace of decline in energy intensity by 2.8%, three times the rate seen in the last 25 years. This negates the impact of economic growth on global primary energy demand, which by 2050 ends up 6% below its 2014 level.

Combined with an accelerated switching to greener fuels, it leads to drastic reductions to energy-related CO2 emissions by an average of 2.4%/yr.

The Renewal scenario leads to a sustainable energy future, achieving the 2degC target, but it is very challenging to achieve. Eirik Waerness, Chief economist in Statoil, said: “Unfortunately, many factors today work against such a transformation.”

In Rivalry national interests and short-term priorities direct policy making, with climate scepticism running high. It leads to a multi-polar world, with most countries delivering partially on their Paris commitments, but without any tightening taking place, and with the agreement gradually losing its relevance.

Challenging geopolitics hamper international trade and the deployment of new technology, limiting economic growth below the levels achieved in the Reform and Renewal scenarios. As a result, global GDP grows more slowly, reaching 1.9 times the 2014 level.

Policy and regulatory attention to local environmental problems is sustained, but concerns for global issues are not.

As a result, energy intensity declines, but only by 1.1%/year; global primary energy increases by 2020 by 31% above 2014 levels; and global CO2 emissions increase on average by 0.6%/yr. Rivalry is clearly unsustainable from a climate perspective.

One interesting observation is the outlook for coal. At present it covers about a quarter of global primary energy demand. Despite environmental concerns, coal demand in Reform declines only to 21% by 2050 and it actually grows to over 28% in Rivalry.

Only in the Renewal scenario this drops substantially, to 8% by 2050. While coal remains a serious contributor to global energy demand, it stops gas from increasing its foothold.

Oil market outlook

Following the agreement last year by Opec and Russia to cut oil production and its Renewal last month, oil producers hoped that the market would stabilise. But the strong US shale oil production recovery has dampened that.

This reinforces the view that US shale oil will end up acting as a balancing point, imposing a cap on global oil prices and keeping them low in the $50-$55/barrel range.

Oil demand growth in the 2020s comes mainly from the transportation sector, accounting for half of all demand. During the same period more people in emerging markets will move into the middle class, increasing the demand for goods and services that require energy and oil.

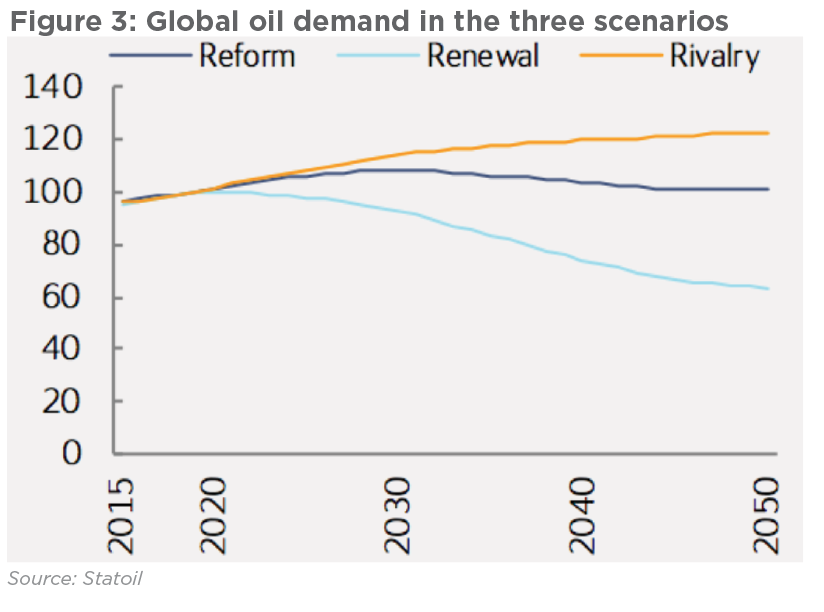

But the drivers impacting long-term development of global oil demand vary and have significantly different impacts in the three scenarios (figure 3).

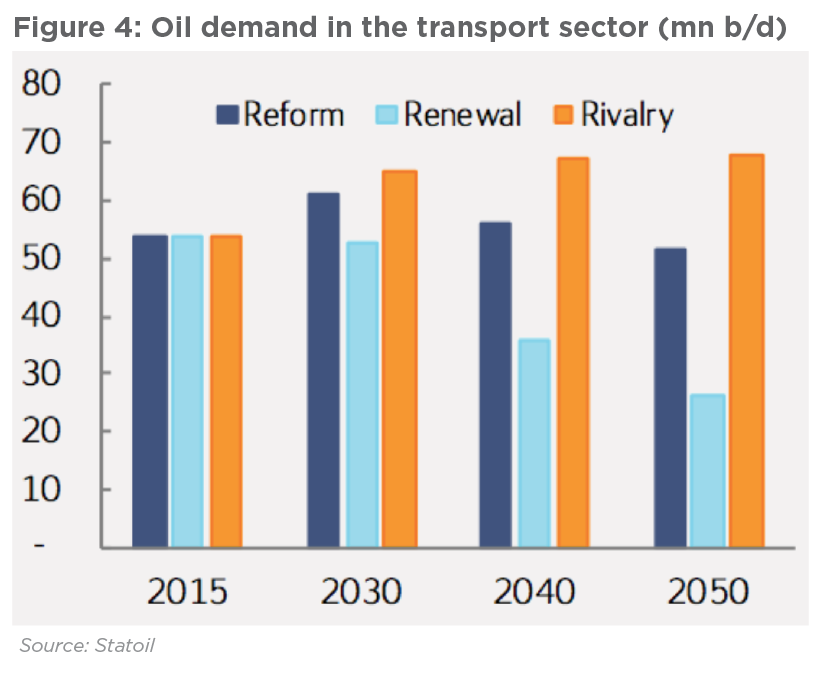

In Reform, electric vehicles (EV) become competitive during the mid-2020s, but market penetration is still relatively low and the impact on oil demand is small. Transport oil demand grows initially by about 15% by 2030, before it declines by 4% by 2050 compared to 2015 levels (figure 4).

Oil demand peaks around 2030 at 109mn barrels/day and decreases towards 100mn b/d by 2050 compared with 97mn b/d now. The main drivers are increased efficiency combined with growing electrification and EV penetration.

In Renewal, global climate policy efforts and increased support to research and technological development accelerate the penetration of EVs to about 90% of private vehicles and shift demand from road to mass public transport.

This keeps transport oil demand by 2030 at 2015 levels, declining by 50% by 2050 compared to 2030 levels.

Oil demand peaks by about 2020, declining to 60mn b/d by 2050, Figure 3. The main drivers for this demand reduction are rapid electrification, EVs, larger efficiency gains and changing consumer preferences. But oil will still be needed for heavy duty and maritime transport, aviation and petrochemical industry growth.

In Rivalry, transport oil demand carries on increasing and by 2050 it is up by 28% on 2015 levels, mainly driven by slower EV penetration and lower efficiency gains.

Oil demand continues to grow throughout the forecast period in Rivalry, increasing demand to over 120mn b/d by 2050. The main drivers are slower electrification, less improvement in efficiency gains and waning and inconsistent focus on climate policy.

However, demand for oil continues increasing in the petrochemical sector, driven mostly by GDP growth.

Through further capacity expansions in the Middle East and Russia and steady increase in US shale oil output the need for high-cost non-Opec supply is reduced, both for the Reform and Renewal scenarios.

This is not the case for Rivalry – continuous increases in oil demand will require contribution from non-Opec producers to balance the market. The amount of reserves needed to meet demand in Reform up to 2050 is 1300bn barrels. In Renewal and Rivalry, the requirement is 1000bn and 1400bn barrels, respectively.

The IEA estimates remaining technical recoverable oil resources to be 6118 bn barrels, while proven reserves are estimated to be 1700bn barrels – sufficient to cover the accumulated demand in all three scenarios.

Gas market outlook

Present global gas markets are still struggling with a glut of supplies and low gas prices. However, these spur competitiveness and provide market opportunities, particularly for price-sensitive emerging markets.

The start-up of US LNG exports and the rapid growth in US shale gas production will be having a similar effect on global gas supplies and prices as US shale oil. US LNG is already having an impact on prices, contract trends and destination flexibility.

LNG is expected to account for about half of globally traded gas by 2035, compared to some 30% in 2015, as gas markets become structurally integrated and LNG supply goes up.

Global gas demand increases in the 2020s for all three scenarios, but in Renewal it declines beyond 2030. But the drivers impacting global gas demand vary and have significantly different impacts in the three scenarios.

In Reform global gas demand increases in the 2020s, going up by about 22% by 2030 in comparison to 2014, with growth concentrated in China, India, the Middle East and Africa. During this period, gas balances indicate a need for new LNG capacity, up to 100bn m³ by 2030.

Demand growth between 2030 and 2050 is expected to be slower, averaging 0.8%/yr.

In Renewal global gas demand growth is slower, increasing only 6% by 2030. It actually declines from 2030 to 2050, down 14% by 2050 in comparison to 2014.

In Rivalry global gas demand increases similarly to Reform throughout the reference period. The reason is that on the one hand security of supply concerns limit gas demand, while on the other hand less new renewable electricity leaves more space for gas in electricity generation. The combined effect is a gas demand similar to Reform.

Through the medium-term horizon, the global gas market is supplied by four main regions with excess supply: Russia, Australia, the Middle East, and the US.

Gas demand and relative competitiveness vary between the three scenarios, due to drivers like geopolitics, regulatory frameworks, prices, as well as environmental regulations and carbon taxes.

The uncertainty poses significant challenges to producers chasing final investment decisions for new gas projects in regions such as North America and east Africa.

Still, energy hungry markets require energy and price matters. But high oil and gas prices could accelerate the switch to renewables.

In terms of long-term supply, the IEA estimates global technical recoverable natural gas reserves at close to 800 tn m³ and proven reserves at some 200 tn m³, which is comfortably sufficient to meet the estimated accumulated demand in all scenaria ranging between 125 to150 trillion m³. This inevitably leaves the world with a permanent glut of gas and low prices.

Renewable energy

In 2014, renewable energy, defined by Statoil to include among others biomass, hydro, wind and solar energy, made up 14% of global primary energy supply.

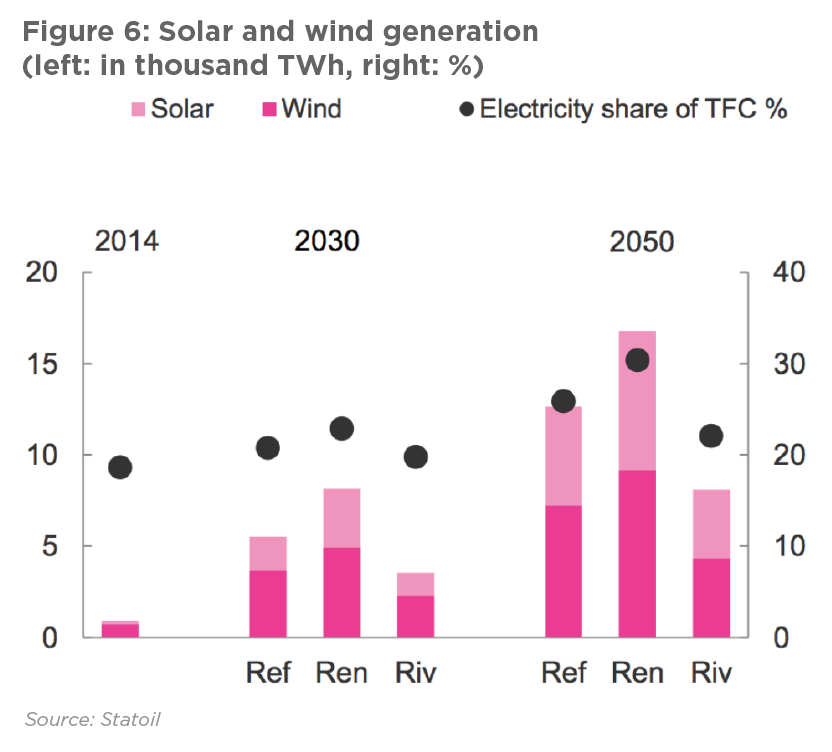

In Reform the electricity share of global total final energy consumption (TFC) from solar and wind reaches 25% by 2050, in Renewal 33% and in Rivalry 16%, Figure 6.

New renewable energy supply growth, solar and wind, has been policy driven. However, subsidy levels are being reduced because the new renewables industries have become so big that continuing to support them has become very costly.

But continued support may not be crucial for continued growth. Subsidy levels are being reduced also because the new renewables industries are becoming increasingly able to stand on their own feet.

But until the large-scale storage problem is resolved, wind and solar power will eventually enter a territory where their variability will become problematic.

As variable renewable electricity grows, the need for, and importance of storage and backup solutions also grow, affecting the economics of new renewable energy. However, rapid technological developments hold potential for significant future change.

Challenges

Statoil considered three scenarios reflecting the difficulty in determining which factors will play dominant roles and have most impact on global energy in the longer-term. Renewal is the scenario that describes a possible route towards energy-related emissions consistent with the 2degC target.

Unfortunately, as Statoil observes, so far there is little to indicate that policies are in fact being adjusted to significantly increase the likelihood of reaching this target.

Political developments to date are indicative of the limitations and challenges being faced to achieve the level of co-operation between countries on framework conditions, on technology development, and on income and burden sharing required to achieve the 2degC target.

A recent, related, article ‘Assessing the Feasibility of Global Long-Term Mitigation Scenarios’ led by Grantham Institute ends up with similar conclusions: “The results highlight how much more challenging the 2degC goal is, when compared to the 2.5 to 4 degC goals, across virtually all measures of feasibility.

Any delay in mitigation or limitation in technology options also renders the 2degC goal much less feasible across the economic and technical dimensions explored.”

The Paris climate agreement signed in December 2015 was ratified in November 2016. Discussions on how to measure progress and scale up emission reduction commitments, and how to raise finance for adaptation and mitigation, are ongoing.

The signatories will reconvene in 2018, but as things stand at present there are many factors making it difficult to achieve the required transformation.

With the US pulling out of the Paris agreement, its planned fleshing out in 2018 will take place in a changed political landscape. Europe, China and India are sticking to it but without the US commitment and lead there are concerns that some countries may waver.

Developments so far indicate that the most likely scenario to succeed in practice is Reform, with countries striving and probably achieving their NDCs.

Studies have shown that these national pledges put the world on track towards a warming of 2.7degC by the end of the century.

Renewal requires immediate action on many fronts, and reality shows that this is a formidable challenge. Individual country interests are still difficult to overcome, let alone go beyond the agreed NDCs and adopt even tighter emission targets.

Statoil’s CEO Eldar Saetre said: “We support a development where the world moves in a sustainable direction where climate change targets are met along with other important sustainable development goals as set out by the UN.”

Statoil’s hope is that its Energy Perspectives 2017 contributes to a fact-based discussion of multiple possible futures. This is essential to arrive at a pragmatic global consensus by 2018 with a realistic chance to succeed.

Charles Ellinas