Mozambique: an unexpected uprising [Gas in Transition]

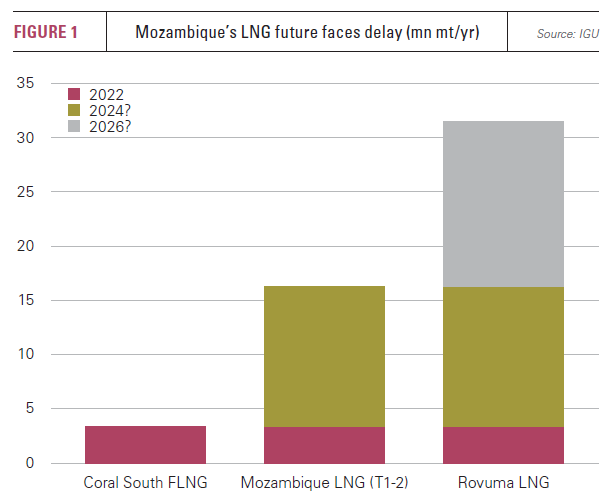

Total has already taken a final investment decision (FID) on the Mozambique LNG project and started construction. ExxonMobil and Eni were expected to have done so last year for Rovuma LNG, but have held off in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and now armed conflict in the Cabo Delgado Province, the site of both developments.

Both projects are big – Mozambique LNG promises 12.88mn mt/yr and Rovuma LNG 15.2mn mt/yr. The government was expected to earn $100bn over 25 years from these developments, a huge sum given that its annual GDP stands at $15bn, while further trains could have earned even more. Yet an insurgency has appeared, pausing development indefinitely and putting a huge question mark over the much heralded projects.

Rebellion roots

The first reports of attacks by a group known variously as Ahlu Sunnah Wa-Jamamah (ASWJ) and al-Shabaab on local people emerged in 2017, and the size of their incursions have increased since then. Dozens of people have been killed in single attacks and LNG industry contractors have been targeted. The official death toll now stands at 2,780, with 670,000 internally displaced across the Cabo Delgado, Niassa and Nampula provinces at the end of 2020.

More recently, in March, the group attacked the previously quiet fishing town of Palma, which lies just 10 km from the Afungi LNG project site and which housed more than 1,000 contractors. Dozens of people were killed in the town, which ASWJ then held for some time against the Mozambican army.

Most of the militants seem to come from Cabo Delgado and other parts of northern Mozambique, with a few from southern Tanzania. There have also been reports of militants being intercepted sailing across the Indian Ocean to join ASWJ.

Project suspension

Total had already paused work on its project earlier this year but, on April 26, after the Palma attack, the French firm and its engineering contractors McDermott International, Saipem and Chiyoda Corporation indefinitely suspended work, declaring a force majeure. In a statement, Total said that the decision was “the only way to best protect the project interest, until work can resume”, while the consortium “has agreed with lenders to temporarily pause the debt drawdown”.

Sheltered from the onshore conflict, Eni’s Coral South floating LNG scheme is proceeding as planned and should deliver production capacity of 3.4mn mt/yr. However, the transformative 29mn mt/yr capacity promised by the two onshore projects now faces a period of uncertain delay with the possibility that the ExxonMobil/Eni consortium does not proceed to an FID, unless there is a rapid improvement in the security situation that guarantees the long-term safety of these multi-billion dollar investments.

Militant aims

There is some debate over the extent to which the insurgents can be described as Islamists or not. There are several reasons to believe that they are, including their tactics, such as brutal mass beheadings, which appear to have been copied from Islamic State (IS). In addition, they claim affiliation with IS, which in turn claims responsibility for the attacks. Finally, the name sometimes used by the group, al-Shabaab, suggests a link with the al-Shabaab Somali Islamist group.

However, any strong link with IS seems to have emerged more recently, as the local militants appear to have been flattered to be connected with the international group, while IS has been keen to associate itself with a growing movement, following its own military reversals in Syria and Iraq. Moreover, noted Mozambican commentator Joseph Hanlon says that the use of the name al-Shabaab is not evidence of a direct link with the Somali militants as the term is often translated merely as ‘the youth’.

However, any strong link with IS seems to have emerged more recently, as the local militants appear to have been flattered to be connected with the international group, while IS has been keen to associate itself with a growing movement, following its own military reversals in Syria and Iraq. Moreover, noted Mozambican commentator Joseph Hanlon says that the use of the name al-Shabaab is not evidence of a direct link with the Somali militants as the term is often translated merely as ‘the youth’.

The plan to impose Sharia law suggests that ASWJ can be described as Islamists, but this policy also appears driven by a desire to distribute LNG revenues more widely, and particularly to keep a higher proportion within the region. The group’s emergence just as the twin onshore LNG projects were being planned suggests that Mozambique’s nascent LNG industry has been a driver of the rebellion, providing a high value economic target over which to fight.

The high profile attack on Palma on March 24 was launched just a day after Total announced that it would restart work on the onshore element of its LNG project, again suggesting a direct link.

Root causes

Militant activity usually grows with some element of popular support, despite the brutality associated with ASWJ. Dismay that Maputo appeared set to spend its LNG income in the south of the country far from Cabo Delgado undoubtedly drove local dissatisfaction.

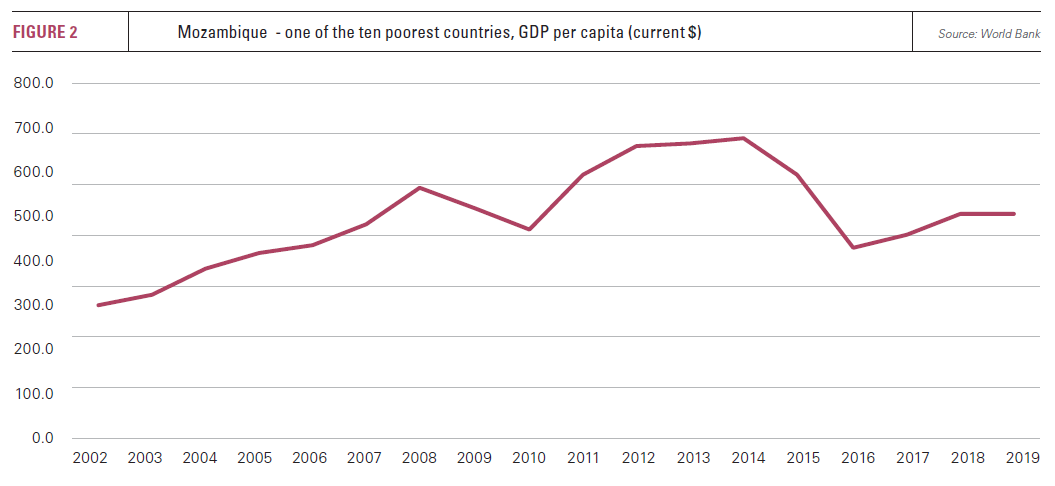

The root cause of the uprising therefore appears to be economic rather than religious. Relatively strong average economic growth of 6% annually has been achieved since the civil war ended in 1992, yet this was starting from a very low base and Mozambique is still one of the ten poorest countries in the world.

At the same time, most of the development achieved since 1992 has occurred in the far south, with the exception of coal industry development: at the mines in Tete Province, at the ports of Nacala and Beira, and on the railways that connect the mines to the ports. Much of the centre of the country has been ignored, helping to fuel renewed activity by Renamo fighters in 2012-14.

National cohesion is weak and the colonial-era pattern of transport infrastructure and trade running overwhelmingly west-east remains. Any north-south railway is still many years off being developed, while north-south road links are limited. The ruling Frelimo party has been in power since independence and, as so often with the parties that won independence across Africa until fairly recently, there is little prospect of it being defeated at the ballot box.

Economic inequalities

Many Mozambicans felt a sense of loyalty to Frelimo for winning the independence war and then defeating Renamo. Yet the latest generation of Frelimo politicians seems to take power for granted and instances of corruption and politically-achieved wealth have grown.

While the number of wealthy people in the far south has increased, there has been little sign of wealth in Cabo Delgado until recently.

Signs of industrialisation began to emerge at the site of the Afungi LNG plant and in Palma, where foreign workers began moving in to new hotels. The growing contrast between their wealth and local poverty, coupled with a feeling that the government was disinterested in correcting it, appears to have created an environment within which the ASWJ could emerge.

The vast majority of local people undoubtedly oppose the militants. Far too many of them have already paid with their lives, while hundreds of thousands more have been internally displaced. Yet a long-term solution to the crisis seems unlikely without much greater local development, as a small proportion of young men with no other apparent economic opportunities and sense of power will continue to be attracted to militant groups.

African parallels

Comparisons can be made with insecurity in other parts of Africa. There have been reports that ASWJ, like Somali pirates, have been motivated by the impact of mass, unregulated offshore fishing on local fishermen.

Similarly, while the Niger Delta militants have pursued very different tactics to ASWJ and have not targeted local people in the same way, the same contrast between hydrocarbon wealth and local poverty has driven instability in the Delta. A succession of Nigerian presidents and military leaders has promised military solutions, but none have emerged.

The Mozambican army has had little success in countering ASWJ, which has repeatedly taken and held towns in Cabo Delgado. The military has also been accused of its own human rights abuses. The government has recruited private security companies to fight the group, most recently South Africa’s Dyck Advisory Group, which is now training local forces. However, Maputo has been reluctant to accept the military support that has been offered by the US and other Southern African Development Community states.

The Mozambican army has had little success in countering ASWJ, which has repeatedly taken and held towns in Cabo Delgado. The military has also been accused of its own human rights abuses. The government has recruited private security companies to fight the group, most recently South Africa’s Dyck Advisory Group, which is now training local forces. However, Maputo has been reluctant to accept the military support that has been offered by the US and other Southern African Development Community states.

Future at risk

LNG exports could change Cabo Delgado beyond recognition, but experience of similar oil and gas developments elsewhere indicates the importance of spending a large proportion of the revenue within the province and spending it wisely. Oil and gas companies generally take the position that their investment is generating billions of dollars in export revenues that governments can then use on infrastructural projects and social spending. It is understandable that they do not want to get involved in domestic political and economic decisions.

Yet the fate of the Afungi plants hang in the balance, and it is in the direct interest of the investors to be talking with the government about tackling the economic imbalances that gave rise to ASWJ, as well as measures to defeat the brutal group militarily. The 70,000 jobs expected to be created by the three LNG projects should help promote local growth, but long-term it is vital that they are not confined to security and catering roles, with comprehensive training and education programmes launched to bring local people into technical positions.

|

Coral South on course to provide first LNG for Mozambique Coral South is a gas field lying in Mozambique’s Area 4, which is being developed by Eni using a 3.4mn mt/yr floating LNG (FLNG) facility. 450bn m3 of gas will be produced and liquefied from the south area of the field using six linked subsea wells. All of the LNG produced will be bought by UK oil major BP under a 20-year contract with an option for a ten-year extension. Other Area 4 shareholders are China’s CNPC, Portugal’s Galp, South Korea’s Kogas, Mozambican state company ENH and ExxonMobil. Coral South FLNG is expected to start up in 2022. The Coral South FNLG hull was built in South Korea and launched in January 2020. It is 432 metres long and 66 m wide, weighing in at about 140,000 tons. The eight-story living module has already been installed and will house up to 350 people. The last of the 13 topside modules were installed in November 2020. Drilling the six wells began in 2019 in water depths of about 2,000 m and will have an average depth of around 3,000 m. |