Energy Needs Molecules: Gasunie [Gas Transitions]

The Dutch gas industry surprised the international gas world when it introduced, two years ago, a new strategy under the name of Gas by Design. Under this strategy, the use of natural gas would be curtailed drastically in the Netherlands. Gas would only be used “when more sustainable alternatives are not readily available and when it provides the best value for society and the end-user.” What is more, by 2050, any gas remaining in the system would be “a combination of sustainable gases such as biogas, biomethane and hydrogen.” Natural gas would only still be used if and when emissions are captured.

The Dutch gas industry surprised the international gas world when it introduced, two years ago, a new strategy under the name of Gas by Design. Under this strategy, the use of natural gas would be curtailed drastically in the Netherlands. Gas would only be used “when more sustainable alternatives are not readily available and when it provides the best value for society and the end-user.” What is more, by 2050, any gas remaining in the system would be “a combination of sustainable gases such as biogas, biomethane and hydrogen.” Natural gas would only still be used if and when emissions are captured.

For outside observers, the new strategy, which had been developed in 2016 by the two major industry associations KVGN (the Royal Association of Gas Companies in the Netherlands, including Shell, Gasunie and Gasterra) and Nogepa (the association for oil and gas exploration and production companies), was difficult to comprehend. The fact that the Dutch gas sector, for over 50 years the mainstay of the North West European energy system, seemed prepared to happily oversee its own demise came as a shock to many in the gas world.

Earthquakes

Yet the industry may not have had much choice. In the preceding years, the country, whose economy had been wedded to natural gas since the start of production from the huge Groningen field in 1963, had suddenly turned against gas. The major reason for this were the earthquakes which had been hitting people in the Groningen region, in particular since the earthquake in the town of Huizinge on August 16, 2012. Another important reason was the threat of climate change and the broadly felt need to reduce CO2 emissions. (See my earlier article Why the Dutch lost their faith in natural gas.)

The government, which in 2013 in a key energy policy document, the Energy Accord, had barely mentioned natural gas, suddenly decided that the country had to reduce its gas use as much as possible. Responding to public outrage over the earthquakes, it even took the historic decision, on March 29, 2018, to phase out production from the Groningen field altogether, leaving as much as 700bn m³ in the ground – equivalent to some 10 years of UK gas consumption.

The latest major policy proposal, the Climate Accord, which will most likely be adopted in some form by the parliament in June 2019, includes not only full decarbonisation of industry and electricity generation by 2050, but also of heating in the built environment. It aims for all Dutch buildings to be disconnected from the gas grid by 2050. Currently some 95% of buildings in the Netherlands are heated by natural gas.

So, clearly by 2016 it had become urgent for the Dutch gas industry to formulate some kind of response to the pressure it felt itself under. Nevertheless, according to Vermeulen, who has had many prominent positions in the Dutch energy sector over the last three-and-a-half decades, for the industry the turn against gas did not come as a big surprise. “In fact”, he says, “it was part of a larger trend that we were already quite aware of and prepared for. We had been thinking about how to make the gas sector more sustainable for at least a decade.”

Pendulum

Vermeulen says it was quite understandable that when the Netherlands started getting serious about climate policy, it would first look at the electricity sector. “The Energy Accord of 2013 was basically a big push for offshore wind with some other bits added,” he said. At that time, no one was thinking about “green molecules” yet, he notes. “We have the best and cheapest gas network in the world. There was no incentive to look at gas first.”

Then when gas suddenly did get into the picture, “the pendulum completely swung the other way,” says Vermeulen. “That had a lot to do with the earthquakes. The idea, we have to stop with Groningen gas, suddenly turned into, we have to stop with all gas. Call it the dialectics of progress.” More recently, the pendulum has swung back again, notes Vermeulen. “Now everybody is concerned again about the costs of climate policy.”

But he says, “whichever way the pendulum will swing – and that depends on factors like earthquakes, Putin, the LNG market, how much we want to get ahead of Europe in climate policy and how much Europe will want to be ahead of the world – the trend will remain the same: we will move to sustainable molecules. And this will cost money.”

The realisation that the trend towards decarbonisation is unstoppable led the Dutch gas industry to develop its Gas by Design strategy, explains Vermeulen. “It was the result of our thinking about how best to use gas in the energy system of the future. Where does it have most value? Where can it be most easily replaced? Gas by Design means making a smart energy mix. In those areas where gas is difficult to replace, you will want to make the molecules more sustainable and use biogas or hydrogen.”

The added value of the strategy, says Vermeulen, is that the gas industry is seen to be taking a pro-active rather than defensive stance in the climate debate. Vermeulen: “We want to stay a trusted discussion partner of the government and other stakeholders.”

Strategic pillars

For Gasunie itself, the new strategy is also having far-reaching repercussions. The company, owned 100% by the Dutch state, has identified four new strategic “pillars”: hydrogen, “green gas”, carbon capture use and storage (CCUS) and heat. Vermeulen says: “For us, hydrogen and green gas (e.g. biogas), are the real sustainable tracks. But if you want to speed up decarbonisation, you also need to invest in waste heat and CCS.”

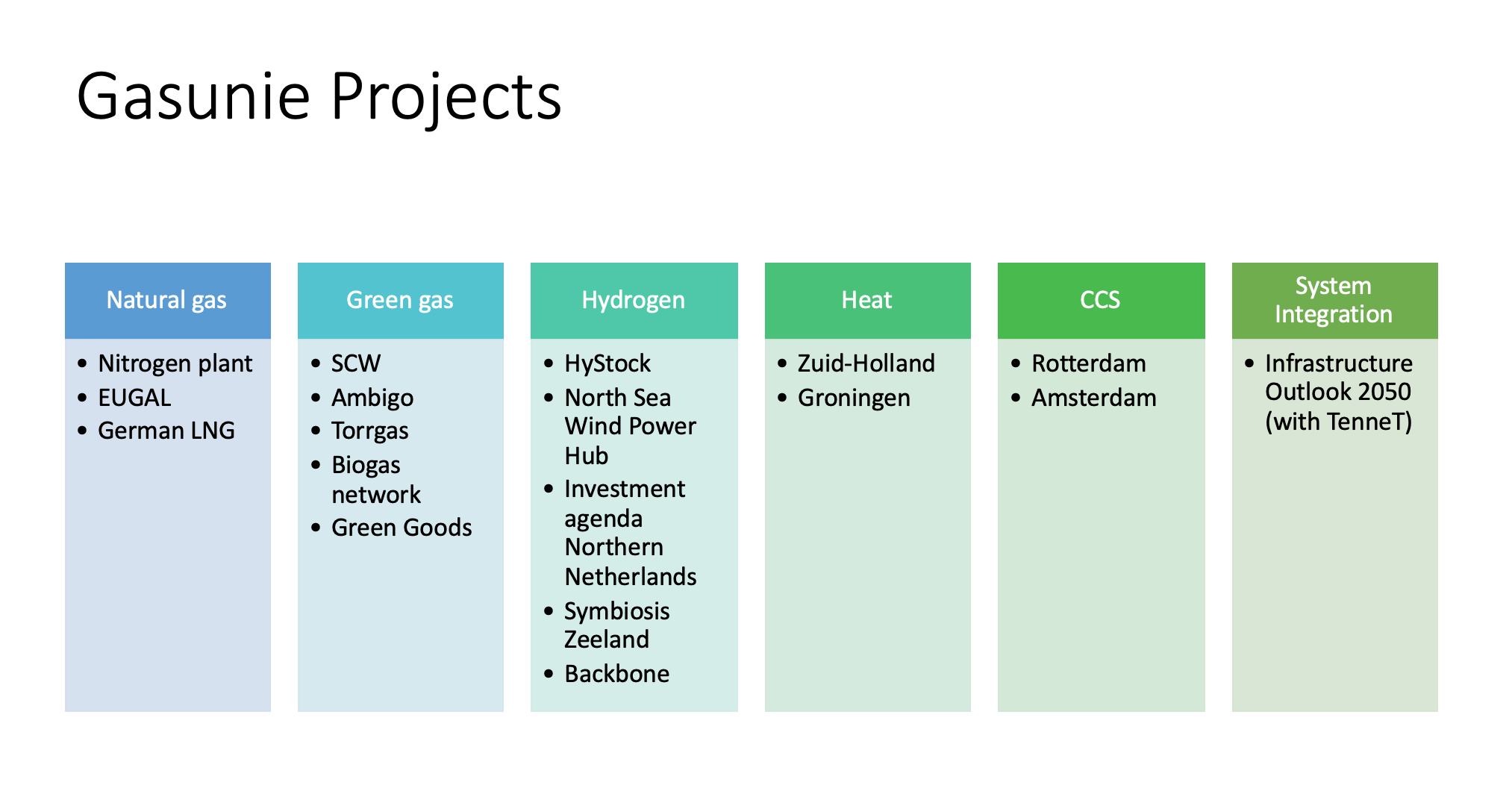

In just a few years, Gasunie has become active in a wide range of projects that indicate the new direction the company is taking.

As just one example: on June 26, King Willem-Alexander will be opening a new 1-MW production facility for “green hydrogen”, Hystock, which Gasunie has built in the town of Veendam near Groningen. Hydrogen, Vermeulen says, is very likely to be one of the energy carriers of the future. “I don’t think there will be one winner, but we are convinced that we will continue to need molecules. In that context hydrogen is one of the better options. But we will need to produce a lot of renewable energy to make hydrogen happen. And the costs of electrolysis will have to come down. It’s possible, worldwide a lot of effort is being spent on this, but it will be difficult.”

Gasunie is also active in building new large-scale district heating networks, in particular in the Rotterdam-The Hague region, where there is a lot of industrial waste heat available and a large horticultural sector that needs a lot of energy. “Our speciality is building large-scale transport infrastructure. We can do that for gas, but also for heating or for CO2. We know what it takes to build these systems, technically but also economically and in terms of regulations. It’s essentially the same process as building gas pipelines.”

Gasunie is also a partner in the two most advanced CCUS projects in the Netherlands, Porthos in the Rotterdam region and Athos in the region Amsterdam-IJmuiden. Both projects aim to capture CO2 from industrial installations, partly re-use it, for example in greenhouses, and partly bury it underground, in empty gas fields offshore.

Will these controversial CCS projects ever get off the ground? “We are ready for them”, says Vermeulen. “I believe climate change is such an urgent and big issue that we need to use CCS as a temporary measure to speed up decarbonisation. If we talk about costs, then CCS in industry is a lot more efficient than removing houses from the gas grid.”

Integrated vision

In February Gasunie, together with electricity transmission system operator Tennet, published an Infrastructure Outlook 2050, which, says Vermeulen, “for the first time presents an integrated vision on what infrastructure investments may be needed in gas and electricity in the Netherlands and Germany to create a sustainable energy system in 2050.” What the two companies found, says Vermeulen, is that, “we need to invest a lot of money. And it’s not a simple picture.

“As a result of the energy transition, infrastructure companies are faced with the question: when do we need to invest? In the past, we planned ahead 25 years – and we didn’t need anybody’s help. Now we are faced with a lot of uncertainties. How much hydrogen will we be using? How much will come from the Sahara? And we can’t do it alone anymore. We need to co-operate.”

Despite all the uncertainties and questions, Vermeulen has no doubt about the course Gasunie and the Netherlands – indeed northwest Europe – are following. “I realise that for many people in the industry this is difficult to grasp. Worldwide the traditional gas industry will still see enormous growth over the next decades. Look at all the LNG projects going on. And this is good because it will lead to lower emissions. But in Europe, especially the northwest, we are looking at lower gas use and a migration to sustainable gas. Here industry is building a competitive edge on the basis of green molecules.”

In 2050, concludes Vermeulen, “Northwest Europe will have a climate neutral gas supply. With green molecules and some CCS. I believe the rest of the world will be able to learn from our experiences. And we will develop knowledge and products that we will be able to export.”

How will the gas industry evolve in the low-carbon world of the future? Will natural gas be a bridge or a destination? Could it become the foundation of a global hydrogen economy, in combination with CCS? How big will “green” hydrogen and biogas become? What will be the role of LNG and bio-LNG in transport?

From his home country The Netherlands, a long-time gas exporting country that has recently embarked on an unprecedented transition away from gas, independent energy journalist, analyst and moderator Karel Beckman reports on the climate and technological challenges facing the gas industry.

As former editor-in-chief and founder of two international energy websites (Energy Post and European Energy Review) and former journalist at the premier Dutch financial newspaper Financieele Dagblad, Karel has earned a great reputation as being amongst the first to focus on energy transition trends and the connections between markets, policies and technologies. For Natural Gas World he will be reporting on the Dutch and wider International gas transition on a weekly basis.

Send your comments to karel.beckman@naturalgasworld.com