China: economic revival will require more LNG in 2023 [Gas in Transition]

At the start of 2022, expectations about Chinese gas and LNG demand were bullish. In 2021, consumption had increased by 12.8% to 378.7bn m3, well above the 8.1% growth in domestic gas production to 209.2bn m3, according to BP data.

The gap was filled by a 17.3% increase in imports to 162.7bn m3. This included an 18.5% hike in piped supplies to 53.2bn m3 and a 16.8% jump in LNG imports to 109.5bn m3 which, inter alia, meant China became the world’s largest single LNG importer..png)

More of the same was expected for 2022. As late as April, the Economics & Technology Research Institute (Etri), a subsidiary of state-owned energy company CNPC, was projecting that gas consumption would increase by 8.2% year on year, driven by demand from the power generation and industrial sectors. With gas production projected to increase by only 6.2%, Etri anticipated that this would require a double-digit increase in gas imports to about 185bn m3.

Etri was far from alone in expecting substantial growth in gas demand and imports in 2022, but as the year wore on analysts began tempering their growth projections.

In August, the China National Environment Agency was estimating gas consumption at about 375-380bn m3 – much the same level as in 2021. By December, the National Development and Reform Commission estimated that apparent gas consumption during the ten months to October was 299.9bn m3 – representing a near-unprecedented fall of 1.1% year on year. Barring a late surge in demand, it seems likely that gas consumption in 2022 could be as little as 350bn m3.

Projections thrown off course

Why were the initial projections so wrong?

The main reason was China’s faltering economy. While Etri had projected gas demand growth would be lower than in 2021 because of tighter Covid-19 restrictions, the Institute and most other forecasters underestimated the severity of the impact of China’s zero-Covid policy on economic activity.

The economy was also affected by other factors, including the war in Ukraine and a jittery property market. GDP is now expected to have risen by a mere 3% year on year in 2022, compared with over 8% in 2021.

The economic malaise was compounded by the adverse impact of inter-fuel competition. In particular, the surge in international gas prices resulted in increased coal use, for instance in the domestic heating sector. Gas demand growth in the years up to and including 2021 had been driven in large part by the shift from coal to gas use in the residential and industrial markets. But much less substitution occurred in 2022.

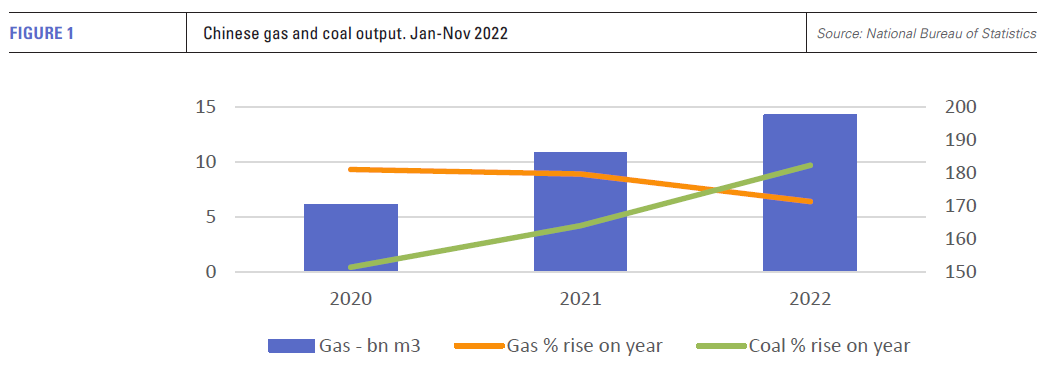

The changing fortunes of Chinese coal, until recently seen as beginning a downward spiral, are apparent from National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) data. In the eleven months to November 2022, coal output increased by 9.7% year on year to 4.09bn mt (see figure 1).

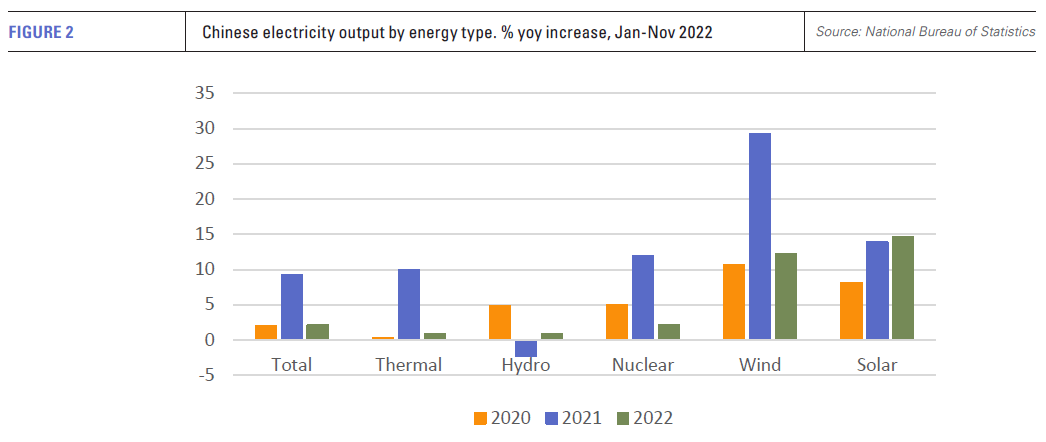

Gas demand was also hit in some regions by lower gas use in the electricity sector (see figure 2). Total power generation increased by only 2.1% year on year in the eleven months to November, compared with 9.2% in the same period of 2021, with fossil-fuelled generation growing by only 0.8% against 9.9% in the same period of the previous year.

Gas demand was also hit in some regions by lower gas use in the electricity sector (see figure 2). Total power generation increased by only 2.1% year on year in the eleven months to November, compared with 9.2% in the same period of 2021, with fossil-fuelled generation growing by only 0.8% against 9.9% in the same period of the previous year.

However, the picture across China was uneven. Some gas-fired plants in eastern China saw much-increased output in July and August as a result of surging power demand due to high temperatures and lower electricity deliveries from drought-hit hydropower plants in western China..

The impact on imports of lower gas demand because of subdued economic growth and competition from coal was compounded by steady growth in China’s own gas output. Etri’s projection of a 6.2% increase in output in 2022 is likely to prove accurate. Production was up 6.4% year on year at 197.4bn m3, during the eleven months to November, according to data from the NBS.

Outsized impact on imports

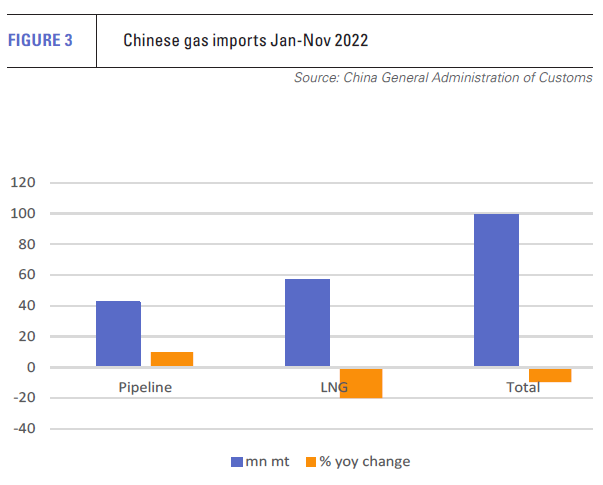

The impact of these factors on gas imports was large. According to the General Administration of Customs, imports of pipeline gas and LNG during the eleven months to November fell 9.7% year on year to 99mn metric tons (135bn m3) (see figure 3).

At the same time, there was a shift in the composition of imports in favour of piped gas. The customs data show that pipeline imports increased by almost 10% year on year to 42.1mn mt in the eleven-month period, while LNG deliveries plunged about 20% to 56.9mn mt.

The jump in pipeline imports mainly resulted from increased supplies from Russia through the Power of Siberia-1 pipeline. Commissioned in 2019 and due to deliver 38bn m3/yr at full capacity from the mid-2020s, the pipeline delivered 7.6bn m3 to China in 2021.

For much of 2022, the pipeline operated at a higher than contracted level, at the peak on December 28 exceeding its daily obligation by 18.7%. On December 30, Russian President Vladimir Putin said in a video conference with Chinese President Xi Jinping that sales through the pipeline from January to November had totalled 13.8bn m3. Customs data indicate that Russian imports in November totalled 0.85mn mt – about double the November 2021 level – taking imports for the eleven-month period to 5.67mn mt, up 24% on the same period of 2021.

A year that started with China having become the world’s largest single LNG importer almost certainly ended with it ceding the title back to Japan. It also saw a marked shift in Chinese LNG buying away from spot purchases and towards term contracts (up to about 80%).

Several more contracts were signed towards the end of the year, including a 27-year, 5mn mt/yr contract inked by Sinopec and QatarEnergy.

2030 outlook uncertain

What can be expected this year -- a return to robust economic growth, or another damp squib like 2022? The indications are unsurprisingly mixed. China is a country where relatively small changes in GDP growth, relative fuel prices, seasonal temperatures, and economic or environmental policies, can translate into significant changes in gas and LNG requirements.

China’s sudden ending of the zero-COVID policy and reopening from December is widely expected to kick-start GDP growth, albeit after a possible contraction in the first quarter.

China’s sudden ending of the zero-COVID policy and reopening from December is widely expected to kick-start GDP growth, albeit after a possible contraction in the first quarter.

In December, the banking group HSBC projected 5.2% growth for 2023, while Morgan Stanley expected 5.4%. However, much will depend on developments in the local property market and consumer spending, as well as overseas developments centred on the revival of freer-flowing global manufacturing activity and trade.

The changing economic environment will have an obvious impact on gas demand but, against the background of continuing high gas prices, use of the fuel will also depend on Beijing’s policy towards coal. In the current high gas price environment, recent falls notwithstanding, coal use will not be reined in on environmental or political grounds before the end of the current winter heating season.

Over the medium term, the prospects for renewed curbs on coal use, for instance through further coal-to-gas substitution programmes in northern China, appear to have retreated.

Hydro reservoir levels remain low, which is likely to support gas use in eastern and to some extent southern China. Reviving economic activity in these regions should also stoke power demand.

If demand rises, the gap will be filled by LNG

That gas consumption will rise in 2023 is generally accepted, although whether the bounce back from 2022 reaches double-digit levels remains to be seen. Growth in domestic gas production is unlikely to be higher than in recent years, meaning much of the increase in gas demand will have to be met by imports. In late 2022, the state-owned energy company CNOOC projected that gas imports in 2023 would increase by 7% year on year.

Some of this increase will be met by additional pipeline imports, notably from Russia. Growth prospects elsewhere are less certain.

Imports from Turkmenistan are set to increase, but only in the longer term, while in the near term there is a question mark over supplies from other Central Asian countries. Increasing domestic demand in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan has put pressure on export sales to China -- Uzbekistan temporarily suspended supplies in late 2022 to prioritise local demand.

Russian suggestions that it could supply gas to these countries, allowing them to sell more to China, have met with a lukewarm response.

As a result, if Chinese gas demand does grow strongly in 2023, it will have to be met largely by more LNG imports. In November, China’s 24 operational terminals had 109.5mn mt (149 bn m3) of capacity, more than enough to meet increased demand. China’s growing suite of long-term LNG contracts also means that large tranches of its LNG needs are already secured.

Moreover, the emergence of pressure points in the Chinese energy economy, such as the eastern Chinese power generation market, could mean that China will have to return to the LNG spot market with a vengeance, a possibility which would feed through into international prices and Europe’s still outstanding, if reduced, need to refill its gas inventories ahead of winter 2023/24.