High prices derail India’s LNG plans [Gas in Transition]

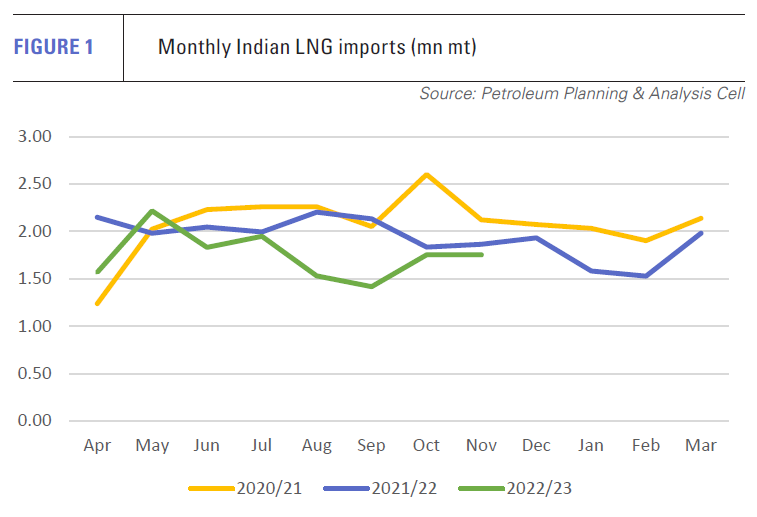

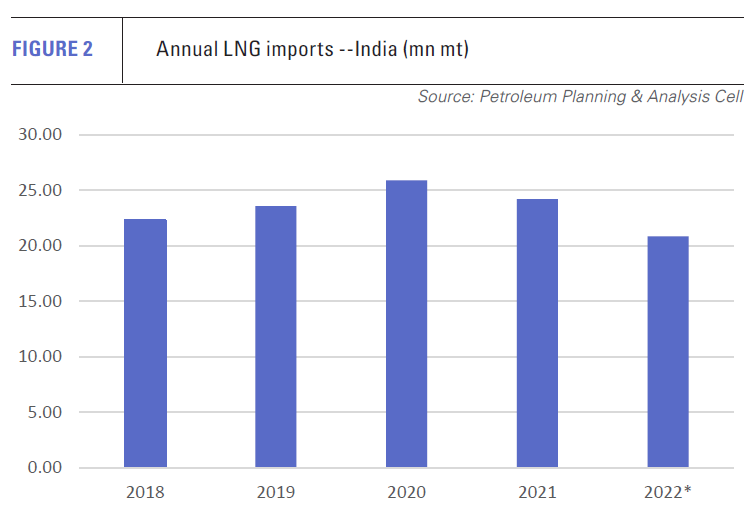

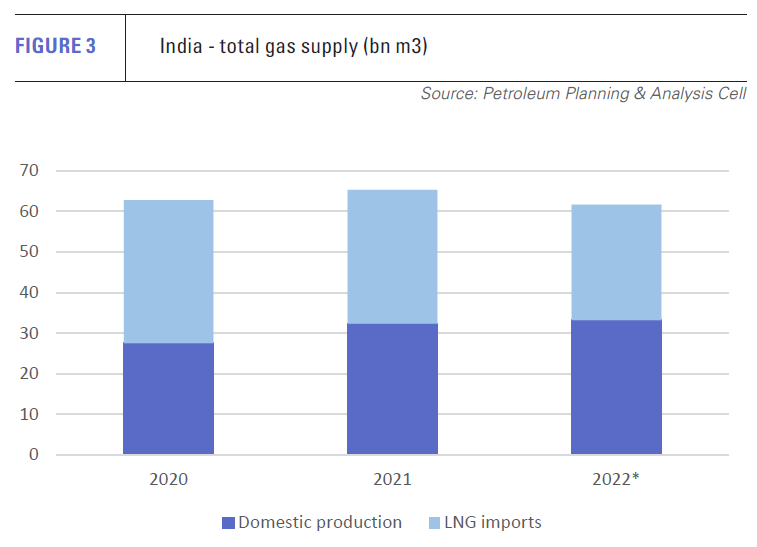

India’s LNG imports have slumped over the last 18 months, hit by rising prices both before and after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Based on data for January-November, LNG imports look likely to have ended 2022 almost 14% down on the previous year. At around 21 million mt, India’s LNG imports only exceeded long and short-term contract volumes by 1 mn mt.

LNG imports also fell in 2021, by 6.4%, mostly concentrated in the latter half of the year, which saw a year on year decline of 10.5%, compared with 2.1% in the first half. The data highlights the price sensitivity of the Indian gas market as LNG spot prices rose sharply in the latter half of 2021.

In the event, reduced LNG imports were compensated for by a significant jump in domestic gas production, which rose from 27.6bn m3 in 2020 to 32.4 bn m3 in 2021, according to data from India’s Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell.

However, a more modest increase in 2022 was insufficient to offset the larger drop in LNG volumes. As a result, having risen by about 2.5bn m3 in 2021, India’s overall gas supply fell by 3.7bn m3 last year.

Gas target receding

A key part of the government’s greenhouse gas emissions reduction strategy is to increase the use of natural gas. The government plans to raise the share of gas in the country’s energy mix to 15% by 2025, compared with 6.3% in 2021.

However, this target is moving backward rather than forward. Natural gas accounted for 6.8% of primary energy consumption in 2020. The reduction in overall gas supply, combined with the increase in coal use in 2022, means gas’ share of the energy mix is almost certain to have fallen further last year.

The flip side of the coin appears to be increased coal consumption. India’s coal consumption rose 14% in 2021 and a further 7% in 2022, according to International Energy Agency (IEA) data. India remains heavily reliant on coal and coal-fired power plants make up around half of total installed generation capacity. The IEA forecasts that India’s coal demand will continue to rise from just over 1.0bn tons in 2022 to 1.22bn in 2025.

The majority of this will be sourced domestically. Domestic coal production exceeded 800mn mt in 2021 and is expected to grow to more than 1bn mt in 2025. India’s draft national electricity plan anticipates that an additional 26 GW of coal-fired power capacity will be developed by 2026-27, despite the country’s rapid expansion of renewable energy capacity.

LNG to play growing role

Despite increased domestic gas production over the past two years, the majority of India’s gas demand growth will be met by LNG imports. Although various international pipeline projects have been proposed, for example the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India pipeline, the prospect of their timely completion has always looked unlikely, despite the support of the states involved.

Russia’s loss of its European markets and its reduced ability to develop further its LNG capacity, as a result of sanctions and the withdrawal of western technology providers, has increased Moscow’s interest in new pipeline routes to Asia. However, reaching India would be very difficult, not just because of the distance and terrain, but because of India’s suspicion of neighbouring countries through which any pipeline would have to pass.

With pipeline import options limited and domestic gas production growth slow, LNG should be the beneficiary. India’s largest LNG importer, Petronet, forecasts that LNG will increasingly come to dominate the country’s gas consumption. The company sees LNG meeting 70% of demand by 2030, up from just under 50% in 2022.

Import capacity plans derailed

This will require more LNG import capacity. At the beginning of 2022, the country had six LNG terminals in operation, totalling 42.5mn mt/yr of capacity. Three were working at just 20% capacity, but, based on the expectation of increased LNG demand, the country was poised to add substantially to its import capacity.

Events have turned out rather differently. Project delays and the loss of two Floating Storage and Regasification Units (FSRUs) have seen these ambitions evaporate.

The Jaigarh LNG terminal was supposed to come on-stream in 2022, but commissioning was delayed owing to Covid-19 disruptions and labour shortages. In addition, late commissioning of downstream infrastructure added to the terminal’s problematic prospects. In August, the 170,000 m3-capacity FSRU Hoegh Giant saw its charter with local company H-Energy terminated.

The FSRU, which at the time of writing was anchored at Limassol, Cyprus, is likely to be deployed soon under a new charter, possibly in Europe.

Delays have also beset the 5mn mt/yr Jafrabad LNG project in the western state of Gujurat with similar results. Originally expected online in 2019, the terminal suffered cyclone damage on more than one occasion. Work was also delayed by the pandemic.

According to developer Swan Energy, the Gujurat State Petroleum Company, Indian Oil Corporation, Bharat Petroleum Corp. and Oil and Natural Gas Corp signed up for the terminal’s full volume over 20 years. The terminal was to use the newbuild FSRU Vasant I constructed by Hyundai Heavy Industries in 2020.

However, as with Jaigarh, delays and higher-paying opportunities elsewhere will see the FSRU redeployed. According to industry reports, the Vasant I has been chartered by Turkey’s Botas for 12 months from the first half of 2023.

However, as with Jaigarh, delays and higher-paying opportunities elsewhere will see the FSRU redeployed. According to industry reports, the Vasant I has been chartered by Turkey’s Botas for 12 months from the first half of 2023.

It is not just FSRU projects which have suffered problems. The 5mn mt/yr onshore Dhamra LNG terminal missed its commissioning date originally set for the second half of 2021. GAIL India and Indian Oil have agreements in place agreed to take 1.5mn mt/yr and 3mn mt/yr respectively. The project was reported by owner and operator Total Adani in September last year as being ready by the end of 2022.

Total Adani is a 50/50 joint venture between France’s TotalEnergies and India’s Adani Group. Once it starts operating, Dhamra will be India’s seventh LNG terminal and the second on the east coast, but the completion timing suggests it will add import capacity to a market with little or no incremental demand at present.

Karaikal LNG is a much smaller facility – 1mn mt/yr – proposed for southern India. It was originally scheduled to start operating in fourth-quarter 2021, but also missed its completion deadline. Work on the terminal, which is being developed by Singapore-based Atlantic Gulf & Pacific International Holdings (AG&P), was reported to have started in February 2020.

However, a Reuters interview with Karthik Sathyamoorthy, president of AG&P’s LNG Terminals and Logistics division, in early December, quoted Sathyamoorthy as saying the company expected to have its first LNG terminal in India by the end of 2024 and that it had other options in addition to Karaikal, suggesting the project has some way to go before completion, if it is completed at all.

Price-sensitive market

LNG spot prices in early 2023 had fallen back to pre-Ukraine crisis levels as mild weather resulted in a low call on European gas inventories in the first half of winter 2022/23. However, pre-crisis price levels were already high and, at over $25/MMBtu, spot LNG prices are still far too steep for India and other South Asian markets.

The problem is not just the result of a lack of LNG supply. India uses a price pooling system for key gas consuming sectors. Domestic gas, particularly that produced from older, regulated fields, is priced much lower than LNG imports, which are bought either on long-term contract, usually priced against oil, or on the spot market.

Gas prices are revised twice a year in April and October to reflect changes in international prices. However, changes are rarely passed through in full, particularly when prices are volatile. From October 1 last year, the price of domestically-produced gas from old fields was raised to a record $8.57/MMBtu. Gas from newer harder-to-produce fields gained a price ceiling of $12.46/MMBtu, up from the previous level of $9.92/MMBtu.

Yet, even at these levels, domestic gas prices are far below the levels required to purchase the spot LNG needed to address the country’s gas deficit. High domestic gas pricing will also act to dampen demand, reducing the government’s ability to increase the share of natural gas in the energy mix.

Moreover, the government’s subsidy bill has increased hugely. Price regulation in the fertiliser and power sectors both rack up debts for state entities. The two sectors reflect the political importance of rural voters in what remains a very agrarian economic system. Fertiliser and power prices for rural communities are kept low, often below the price of production.

Where now?

There is no doubt that India’s plan to more than double gas use as a proportion of the energy mix by 2025 is in serious jeopardy. In the current environment, forecast increases in LNG imports must also be taken with more than a pinch of salt. Coal and renewables are likely to be relied on to fill the gap.

India’s rate of renewable energy deployment is impressive. It has the fourth largest wind power capacity in the world and is the third largest market for solar PV. It is currently third in terms of total renewable power capacity additions. But, at the same time, renewables (not including large hydro) made up only 4.9% of the country’s primary energy supply in 2020 and 5.0% in 2021, compared with 54.1% and 56.7% respectively for coal.

Even taking India’s rapid and accelerating adoption of renewables into account the scale of the challenge in terms of weaning the country of coal is immense. Without increased gas availability, coal use is likely to continue expanding over the next decade with a detrimental effect on national and global GHG emissions, given that India is the second largest consumer of coal after China.

Yet the country’s gas plans are unlikely to get back on track until LNG returns to more affordable levels, perhaps in 2026/27 when large-scale liquefaction investment in Qatar and North America should come to fruition. However, in the interim, with subsidy payments putting an increasing strain on government coffers, Delhi’s enthusiasm for imported gas may weaken.