Asia drives LNG demand growth [NGW Magazine]

Anglo-Dutch major Shell’s latest LNG Outlook 2021 published February 25 shows global demand of 700mn mt by 2040. This is likely to lead to a supply crunch by the middle of the present decade, requiring an increase in investments.

Shell’s key conclusions are that:

- Pipeline gas and LNG will have a key role to play in a decarbonised world – with LNG expected to become the fastest growing source of natural gas and used in hard-to-electrify sectors.

- LNG showed its resilience and flexibility in 2020: despite the major downturn in the global economy, LNG demand grew marginally to 360mn mt in 2020, but at the expense of very low prices, with new investment decisions griding to a halt.

- Complementary spot and term contract structures and cleaner pathways are evolving to drive LNG growth: with an increasing number of buyers and suppliers, the LNG industry has evolved to offer a wider choice of commercial structures to meet changing needs, while net-zero carbon (NZC) commitments will require further innovation to deliver cleaner energy solutions.

Shell’s director of integrated gas, renewables and energy solutions Maarten Wetselaar said that last year, “LNG provided flexible energy which the world needed during the Covid-19 pandemic, demonstrating its resilience and ability to power people’s lives in these unprecedented times.”

NGW asked Wetselaar how confident he was, given all the major country commitments to achieve net-zero emissions carbon by 2050-60, that global demand would rise that much? He said: “We believe that gas and LNG have a significant role to play in achieving net-zero emissions. Both as a partner to renewables as their share grows in the power sector and through coal-to-gas switching. In non-power sectors like industry, transport and heating, gas and LNG have a more pronounced role till net-zero carbon fuel and technologies are developed and available at scale.”

2020 resilience

The recovery in LNG demand in 2020 was led by China, whose LNG imports rose by 7mn mt to 67mn mt, a staggering 11% increase taking advantage of very low prices. India did exactly the same.

However, LNG imports in Japan and South Korea dropped by 4% and 2% respectively.

Demand in Europe, alongside flexible US supply, helped to balance the global LNG market in the first half of 2020.

But 2020 saw high levels of LNG market volatility with both extreme oversupply and extreme tightness during the course of the year. According to the Outlook, global LNG prices hit a record low early in 2020 but ended the 12-month period at a six-year high, as demand in parts of Asia recovered and winter buying rose against tightened supply, extreme weather and supply outages. But prices have since fallen to the ‘normal’ low levels seen in 2019, with spot prices in Japan hovering in the range $5.50-6.00/mn Btu and in north-western Europe in the range $5.00-5.50/mn Btu.

The Outlook expects LNG demand recovery to continue in 2021. But demand in Europe, the Americas, the Middle East and Africa is expected to be mostly flat, with estimates of either limited growth or a slight fall in consumption.

Key role in future decarbonisation

As Wetselaar said: “Around the world countries and companies, including Shell, are adopting NZC targets, seeking to create lower-carbon energy systems. As the cleanest-burning fossil fuel, natural gas and LNG have a central role to play in delivering the energy the world needs and helping power progress towards these targets.”

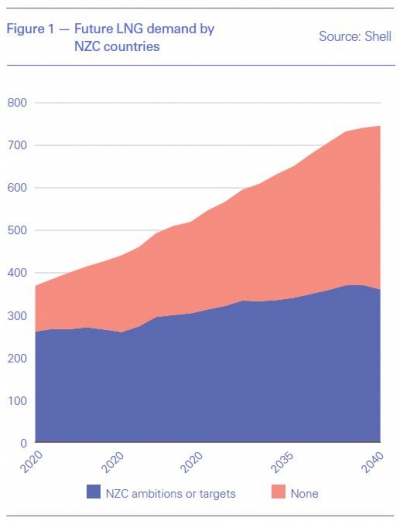

The number of major LNG importing countries committed to NZC keeps rising. It now includes China, Japan and South Korea. Switching away from coal, in addition to increased use of renewables, it will also mean increased use of LNG over the next 10 to 15 years. These countries are expected to account for more than half of future LNG demand to meet their emissions targets (Figure 1).

The LNG industry will need to innovate at every stage of the value chain, from natural gas production to regasification, to lower emissions and play a key role in powering hard-to-abate sectors.

NGW asked Wetselaar how critical was it that liquefaction and regasification processes themselves eliminate methane emissions and leakages, especially given the EU's Methane Strategy. He said: “This year must be the turning point for the oil and gas industry to make unnecessary methane emissions a thing of the past. If the industry does, there are exciting opportunities for natural gas on the pathway to net-zero emissions – with hydrogen, nature-based offsets, carbon capture and storage and more.

“To enable these opportunities, oil and gas companies must continually reduce emissions of methane to near-zero. To start, this requires ambitious and robust policies that steer companies to lower emissions. I am glad the European Commission (EC) has adopted a Methane Strategy as a part of its EU Green Deal. For this strategy, attention is rightly being given to a mandatory monitoring, reporting and verification framework, new regulatory requirements on leak detection and repair, and limitations on routine flaring and venting. I was also delighted to see the EC will examine targets or performance standards for methane emissions. This is needed to assure the future of gas in Europe. But, as the EC itself has made very clear when it presented this Methane Strategy, policies alone are not enough – companies also need to take voluntary action. This is why Shell has set a target to keep its own methane emissions intensity, for both oil and gas, below 0.2% by 2025.”

Evolving LNG markets

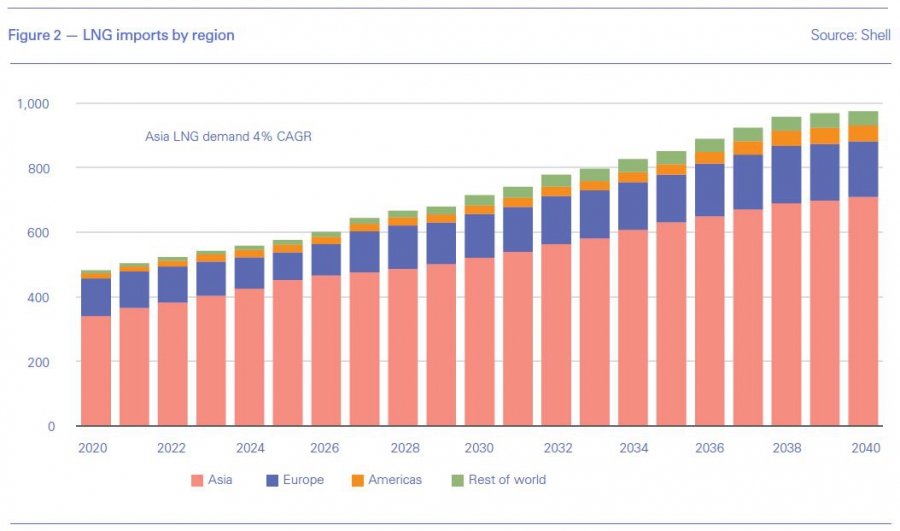

China, India and emerging Asian markets account for most of the growth in future LNG imports, while Europe should return to its pre-2019 levels after reaching record levels as a balancing market in 2020 (Figure 2).

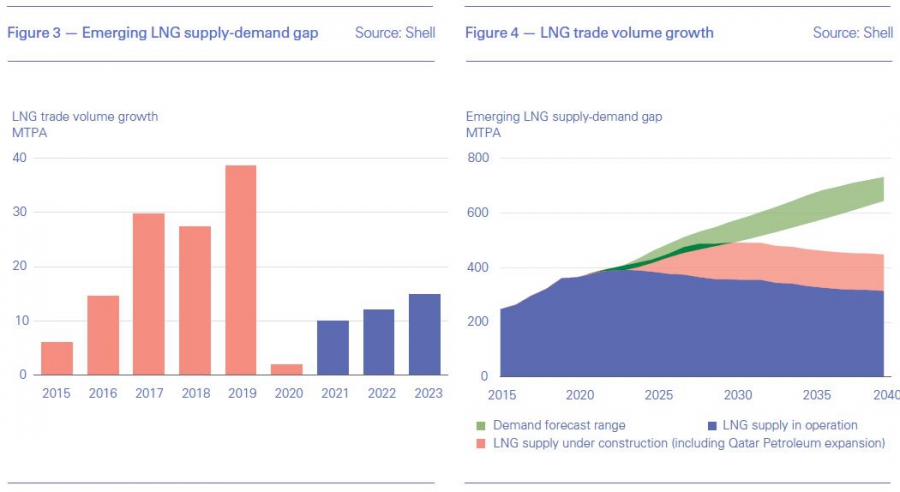

But if demand grows at the upper end of the forecast range, a supply-demand gap could open in the middle of the current decade (Figure 3), with less new production coming on-stream than previously projected (Figure 4). Only 3mn mt/yr in new LNG production capacity was announced in 2020, down from an expected 60mn mt. However, that figure looks less bleak when the Qatar expansion is included, which had project sanction early in 2021.

Shell also expects LNG-fuelled shipping to grow, with the number of vessels more than doubling and global LNG bunkering vessels set to reach 45 by 2023.

Other outlooks see more modest increases in future LNG demand. McKinsey expects “demand to grow 3.4%/yr to 2035, with about 100mn mt of additional capacity required to meet both demand growth and decline from existing projects. LNG demand growth will slow markedly but will still grow by 0.5% from 2035 to 2050, with more than 200mn mt of new capacity required by 2050.”

In a new report Wood MacKenzie says that over three quarters of new LNG supply would be impacted in a 2 °C world. Under this scenario, “gas demand comes under pressure from increased investments in renewables and energy storage in the power sector, as well as efficiency improvements and adoption of new technologies in non-power sectors. In a 2 °C world, green hydrogen becomes a game-changer in the long-term, emerging as a key competitor to gas consumption towards the end of 2040 and achieving a 10% share in the total primary energy demand by 2050. With weaker global gas demand, the space for new developments will be limited.”

In such a situation only about 145bn m³/yr a year of additional LNG supply is needed in 2040.

Shell’s Strategy

Shell held its Strategy Day in February where it explained how it would “accelerate its transformation into a provider of NZC energy products and services, powered by growth in its customer-facing businesses.

A disciplined cash allocation framework and rigorous approach to driving down carbon emissions will deliver value for shareholders, customers and wider society.” Shell also confirmed its expectation that total carbon emissions for the company peaked in 2018, and oil production peaked in 2019.

Introducing the strategy, CEO Ben van Beurden said: “From today, Shell is integrating its strategy, portfolio, environmental and social ambitions under the goals of Powering Progress: generating shareholder value, achieving net-zero emissions, powering lives and respecting nature. Shell’s reshaped organisation will deliver on these goals through the three business pillars of ‘Growth’, ‘Transition’ and ‘Upstream’.”

A top priority will be financial resilience and profitable growth through discipline capital allocation. But equally important is the road to NZC, to be achieved by implementing a comprehensive carbon management approach.

Shell’s aim is to build material low-carbon businesses of significant scale by the early 2030s. In the near term, the strategy will rebalance its portfolio, investing $5bn-6bn/yr in ‘Growth’; $8bn-9bn in ‘Transition’, split equally between integrated gas ($4bn) and $4bn-5bn in chemicals and products; and around $8bn in ‘Upstream’.

Shell intends to extend its leadership in LNG volumes and markets, with selective investment in competitive LNG assets to deliver more than 7mn mt/yr of new capacity on-stream by middle of the decade. The company also intends to continue to support customers with their own net-zero ambitions, with leading offers such as carbon-neutral LNG.

Shell’s strategy prioritises "projects with sector-leading returns." NGW asked Wetselaar if in terms of natural gas and LNG, this will involve divesting less profitable projects and what it means for new investments? His response was that “in our Integrated Gas business we have a competitive funnel of project opportunities and we target selective investment in cash and carbon competitive LNG assets, including backfill and expansion options. This project funnel has an expected average internal rate of return of 14% to 18% and we aim for payback before 2040. We have reduced the unit technical cost of our project funnel by around 40% since 2015, thus ensuring strong cost competitiveness. Our existing Integrated Gas portfolio, the largest of any player in the industry, is already highly cash generative. In 2019, we generated close to $15.8bn ‘cash flow from operations’ (CFFO) and in 2020, despite the pandemic and a low-price environment, we still generated a resilient CFFO of $10.7bn.”

Shell’s strategy does not apply to other legal entities in which it owns investments but has no controlling interest. It plans to put this to a shareholder vote at the company’s annual meeting in May.

Challenges

Even though in India coal-to-gas switching is expected to drive demand for LNG, it will not be without challenges. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), demand for LNG “will greatly depend on the timely execution of planned infrastructure projects, further gas market reforms and the affordability of imported gas for India’s price-sensitive consumers,” but also on the evolution of domestic gas production. However, if lower prices persist, LNG imports can gain further ground in India’s fuel supply mix.

The IEA has also warned that without building additional import capacity, LNG demand growth in Asia would be cut by a half by 2025.

In the meanwhile, final investment decisions taken before 2020 are expected to add 120bn m³/yr of export capacity between 2020 and 2025, not accounting for the expansion of Qatar LNG by about 67bn m³/yr by 2027. Qatar has the advantage that it can produce LNG at a cost lower than its competitors, viable even if Brent crude oil prices fall to $20/barrel.

Slower growth in natural gas demand is likely to create a situation of overcapacity as liquefaction growth outpaces incremental LNG trade, leading to competition among suppliers and lower prices.

In addition, the IEA warns that gas faces significant uncertainty as Asia’s developing economies emerge from the Covid-19 crisis. Despite a lower price outlook, growth prospects for gas continue to rely heavily on policy support in the form of air quality regulations, or other restrictions on the use of more polluting fuels, and on significant investment in new gas infrastructure. Also, in more established markets, gas faces competition from increasingly cost-competitive renewables as well as environmental pressures. Achieving a smooth balancing between LNG supply and demand over the coming years is by no means a given.

Another big factor is what happens in China. The way forward in China’s 14th five-year plan (FYP), expected to be approved in March, will be domestically driven, focusing on technological innovations, environmental sustainability and a low-carbon future. This will reshape China's commodities demand over the next five years, with the beneficiaries likely to be petrochemicals, gas and low-carbon fuel sectors. The balance among fuels will become clearer once the FYP is approved, with huge implications on natural gas and LNG imports.

However, concerns over gas import dependency might still dampen the growth outlook for natural gas. Increased indigenous gas production, pipeline imports and persisting, or even escalating, trade war with the US, could all impact LNG import growth adversely.

The country is already accelerating development of green hydrogen as a fuel for power generation and vehicles, in support of its pledge to achieve peak emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. Eventually that could limit its needs for LNG imports. With tensions between China and the US/Europe expected to continue, a more bipolar world could undermine global energy trade and economic growth.

In Europe the proposed Taxonomy regulation on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment is threatening to leave natural gas projects – including LNG – out of future funding.

Methane emissions continue to haunt natural gas and LNG, with the EU taking decisive steps to reduce methane emissions through its ‘Methane Strategy’. Already, LNG exporters are becoming increasingly aware of the consequences of this strategy. Emission intensity clauses are expected to become more common in LNG contracts. This could restrict supply of higher emission LNG in future.

Right on cue, Tokyo Gas and 14 other Japanese companies have announced the formation of an alliance to enhance the use of carbon neutral LNG to help tackle climate change. Right behind them, Sakhalin Energy, the operator of Russia's liquefaction plant Sakhalin 2, said it is considering shipment of its first carbon-neutral LNG cargo later this year. Gazprom said that it has already delivered its first carbon-neutral shipment of LNG to Europe. Presentations at CERAWeek confirmed that ‘green’ LNG is becoming the norm across the world. This will increase pressure on US LNG to clean its act.

And there is the Biden factor. What the US president does in implementing his climate change pledges might impact the US shale gas and LNG industries. Energy Secretary, Jennifer Granholm, acknowledged that the Department of Energy has legal responsibility to review proposed LNG export facilities and suggested that it could move in step with curbing flaring and leaks from gas pipelines.

Shell is trying to ride both worlds: transition to clean energy, but at a pace that does not impact its traditional business too fast too soon. Its strategy has been criticised by the Financial Times as being “all things to all people,” with its plan to achieve NZC by 2050 aiming to charm everyone, promising “progressive dividends while it shrinks its carbon shadow.”

The FT went on to say that If shareholders are worried that the company has given up on its main source of income, they should rest easy.

Another criticism is that Shell plans to reduce oil output by only 1% to 2% a year until 2030, which leads to an overall reduction of about 15% in the period. Including gas, Shell’s production may be flat.

This does not compare favourably with BP that opted for a 40% cut in oil and gas by 2030. But in terms of shareholder returns, given the currently high oil prices – at least this year – the company may feel vindicated.

Shell’s sees an optimistic future for LNG. But it is not a view shared by everybody. In a fast-changing global energy world many factors, still undefined, have the potential to tip the balance in either direction. The next few years will be telling.