Why axing oil and gas investment is not working [Gas In Transition]

Not only is oil and gas divestment not working as a climate strategy, it is also a key contributor to supply shortages and high prices.

As recently as May 2021 the International Energy Agency (IEA) said that “beyond projects already committed as of 2021, there is no need for investment in new fossil fuel supply in our net-zero pathway.”

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

And yet, elsewhere in the same report, the IEA said that “reaching net-zero by 2050 requires further rapid deployment of available technologies as well as widespread use of technologies that are not on the market yet” – about half the technologies needed to achieve net-zero by 2050 do not yet exist on a commercial basis. “Major innovation efforts must occur over this decade in order to bring these new technologies to market in time.”

It is the contradiction between these two statements that is at the heart of the energy conundrum the world is facing. While almost everybody recognises the need to eliminate emissions by 2050, not everybody is willing to accept that shutting down oil and gas development now – prematurely - is not working.

Pressure by the EU and the US to ditch reliance on oil and gas this decade is increasing – partly driven by the mess in which Europe finds itself as a result of the war - even if renewables are not yet ready to rise to the occasion. On April 21, US climate envoy John Kerry said that “natural gas can provide short-term emissions cuts”, but then put the gas industry on notice – giving it at best a decade to fully grapple with CO2 and methane emissions.

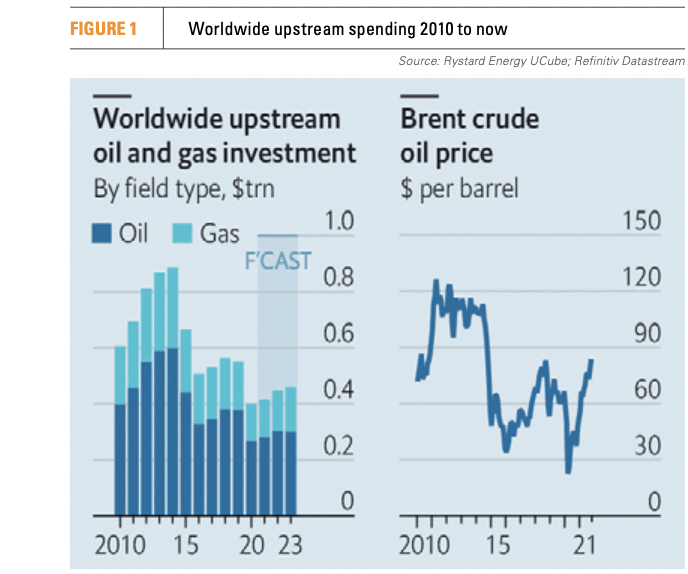

Under pressure from activists, shareholders, financial institutions, governments, and even the courts, over the last few years international oil companies (IOCs) have been scaling down upstream investment. It dropped dramatically following the oil price collapse at the end of 2014 and again in 2020 as a result of the pandemic (see figure 1). Upstream investment is now at about half the 2014 level. But divestment has not led to reductions in demand for oil and gas. This chronic underinvestment gave rise to the dysfunctional global energy market of 2021, a year when the world was coming out of the pandemic and global energy demand was increasing rapidly. As demand carried on increasing, energy supply did not respond in kind, pushing oil and gas prices to astronomical levels.

Under pressure from activists, shareholders, financial institutions, governments, and even the courts, over the last few years international oil companies (IOCs) have been scaling down upstream investment. It dropped dramatically following the oil price collapse at the end of 2014 and again in 2020 as a result of the pandemic (see figure 1). Upstream investment is now at about half the 2014 level. But divestment has not led to reductions in demand for oil and gas. This chronic underinvestment gave rise to the dysfunctional global energy market of 2021, a year when the world was coming out of the pandemic and global energy demand was increasing rapidly. As demand carried on increasing, energy supply did not respond in kind, pushing oil and gas prices to astronomical levels.

And with the war in Ukraine expected to become protracted, this situation is worsening. Increasing sanctions against Russia inevitably takes more and more oil and gas supplies out of an already tight global energy supply market. The way out is not by reshuffling supplies geographically, which inevitably exacerbates price rises even more, but by reducing energy demand where possible and increasing oil and gas production.

But market forces are holding back the expansion of US oil and gas production. Investors are keen to recoup their losses over the period since 2014 and not to flood markets and crash prices back to loss-making low levels. Assurances are also needed that longer-term investments can be recouped beyond the period to 2030.

Supporting an orderly transition

The global oil and gas market was already tight before the war in Ukraine, but Russia’s invasion has magnified the problem. Both the EU and the US recognise that and are striving to find ways to increase oil and gas production. But the emphasis is on short-term measures that cover the period to 2030. This includes squeezing more production out of existing fields and expanding existing facilities. But there is increasing doubt that such an approach will be sufficient. Oil and gas production will not rise fast enough, and not sufficiently, leaving Europe dependent on Russian oil and gas longer. Or, if sanctions continue taking more Russian oil and gas out of the market, causing shortages, the result will be rationing, skyrocketing prices and inevitably huge impacts on the global economy, inflation and recession.

Such an approach is fraught with risks and does not encourage the development of new fields or the construction of new facilities that require longer-term commitments.

It is also important to remember that while this is happening, Europe’s domestic natural gas production is declining, adding to the shortfall and increasing EU’s import dependence.

With most analysts expecting the energy transition to last longer, what is needed is increased investment to boost oil and gas production to the levels required to make that transition orderly. But this will not happen if short-termism continues. This must be recognised through more realistic and longer-term energy planning, supported by policy.

As a result of the high prices, the oil and gas sector is now awash with money to support increased investment. But mixed messaging by the US and the EU discourages that. While the Ukraine war is raging and increasing sanctions on Russia are impacting its oil and gas exports, the message to the IOCs is: do whatever possible to increase oil and gas supplies – but not beyond 2030 for the fear of locking new facilities in for the longer term. As a result, the EU is not encouraging investment in new infrastructure unless it is compatible with its climate plans.

But as Jason Bordoff, a former adviser to the Obama administration and now dean of Columbia University’s climate school, said “you cannot have an energy transition if you’re in the middle of an energy crisis.”

With such policies, investing in new exploration and production becomes risky, limiting what can be done to increase production from existing fields and exports using existing infrastructure. That will not be sufficient, stoking up the energy crisis problems for longer.

An important role for decades

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen’s Green Deal in December 2019 and Joe Biden’s pledge to restrict shale drilling and lower US dependence on fossil fuels by prioritising clean energy legislation after becoming the US president in January 2021, spelt the beginning of the end for fossil fuels – or so they thought. With renewables unable to step in and fill the gap and still limited by intermittency, the euphoria of 2021 – as the world started emerging out of the pandemic - proved to be premature. The Ukraine war has challenged these optimistic positions even further. Events have now led to increasing demand for oil and gas to support the economic revival from the pandemic.

While it is important to accelerate energy transition, the pace depends on how fast new technology is developed and comes on stream at scale. This is a slow process that will take us well beyond this decade. In the meanwhile oil and gas will be indispensable to supplement renewables and provide back-up to keep energy systems stable.

Most energy outlooks are based on broadly similar scenarios. BP’s two key scenarios in its recently published Global Energy Outlook 2022, are:

- The New Momentum scenario captures the broad trajectory along which the global energy system is currently progressing. It places weight both on the marked increase in global ambition for decarbonisation seen in recent years and the likelihood that those aims and ambitions will be achieved, and on the manner and speed of progress seen over the recent past.

- The Net-zero scenario assumes a shift in societal behaviour and preferences which further supports gains in energy efficiency and the adoption of low-carbon energy sources.

According to IEA’s Announced Pledges scenario, between 2020 and 2050 oil demand will decline by 14%, compared with 20% in BP’s New Momentum scenario. The corresponding estimates for natural gas are a decline of 4% and a growth of 25%.

Even the latest McKinsey Global Energy Perspective 2022 projects that gas demand across all scenarios will grow between 10% to 20% by 2035 in comparison to now.

According to McKinsey, even though increasing growth in energy demand will be supplied by renewables, the combined oil and gas contribution to global energy demand will not peak until about 2030 and in real terms decline will be slow, -27% by 2040 and -45% by 2050.

Drastic reductions occur only if the Net-zero scenarios are achieved. For oil, the IEA estimates a decline of 75% for oil and 56% for natural gas. BP predicts declines of 75% and 60% respectively.

Given the Net-zero scenario is more aspirational, while the New Momentum scenario reflects the latest developments in global decarbonisation, reality is likely to be somewhere in-between. Clearly, oil and natural gas will continue to play an important role in global energy demand for decades, requiring continuing investments in new upstream hydrocarbons. But this must also be accompanied by measures to reduce, or even eliminate, carbon and methane emissions.

Concerns

Rising oil and gas prices are not just the result of the war in Ukraine. They reflect chronic underinvestment in the sector, limiting supply and spare capacity that cannot simply be turned on at short notice at the whim of politicians. Underinvestment also highlights the complexities of switching to clean energy on the basis of aspiration rather than a gradual transition based on proven technology.

Reactively rushing into the transition now in the middle of multiple shocks, such as the pandemic, the ensuing energy crisis and the Ukraine war, can be fraught with risks.

And yet the latest IPCC report on the impacts of climate change stresses the need for immediate moves away from fossil fuels if the world is to limit global warming. Clearly what is needed is a balanced transition between the current drive for energy security, energy affordability and the need to tackle climate change.

McKinsey warns that “while developments of the conflict in Ukraine are highly uncertain, today’s decisions could impact the long-term energy transition path towards decarbonisation.” With the conflict and its duration and scale still uncertain and unfolding, it is difficult to predict what its impact will be on the global economy, GDP and energy markets. Getting it wrong will have massive economic and decarbonisation implications down the road.

As we accelerate energy transition, we must be careful not to create the same problems that led us to where we are today. In other words, we should shut down oil and gas development prematurely, in anticipation of renewable technologies still to come. This risks another energy crisis occurring later this decade, due to inadequate supply. The transition needs to be as smooth as possible, avoiding the severe volatility the world has been experiencing since 2021.

It is no longer simply a spike in oil and gas prices. This is a prolonged trend with huge implications on energy costs, food production, industry, transport and so on.

Russian oil and gas supplies cannot be phased out without a replacement at hand. Shifting LNG from Asia into Europe’s broken energy market does not solve the problem. It increases prices everywhere and creates LNG shortages in Asia. What is needed is more LNG globally. But for this to happen the world needs new production - both in terms of new upstream gas production and new liquefaction facilities.

These take years to construct. Starting now, such facilities will not be available until well into the second half of this decade. With a 2030 framework, timing is not favourable to allow a major expansion in oil and gas supply, unless the timeline is extended well beyond 2030. US and European energy policies need to accommodate this, while driving reductions in emissions.

Economic implications

According to a report released by the World Bank on April 26, “the biggest energy shock since the 1970s is expected to keep oil and other energy prices elevated for years as the Russian invasion of Ukraine is changing energy trade flows and consumption and production,” adding that “there was a risk that persistently high commodity costs lasting until the end of 2024 would lead to stagflation – sluggish activity combined with strong cost of living pressures.” The bank called for policymakers to avoid actions that will bring harm to the global economy. The priority must be to deal with the global energy supply crisis if we are to avoid even greater economic impacts.

High energy prices matter. Most narratives appear to concentrate on measures to replace Russian oil and gas and on energy security, which given the worsening events in Ukraine is understandable, but the cost impact so far has not received equal attention. Soon it will have to.

In France, concerns about the cost of living fed into strong voter backing for the far right. They fear a looming economic crisis from the fallout from sanctions from the war. Recent elections have demonstrated this.

As WoodMac points out, high fuel costs and energy shortages can also create a backlash against climate policies, especially for people on low incomes. “If governments want to continue to make progress on cutting emissions, they will need to show that they can deliver energy security and affordability at the same time,” the consultancy says.

Right now, divesting from oil and gas without reducing demand is squeezing supply, raising prices and prolonging volatility. This is even more so in the developing world where growing populations, and aspirations to increase living standards, lead to rapidly rising energy demand that cannot be met by renewables alone.

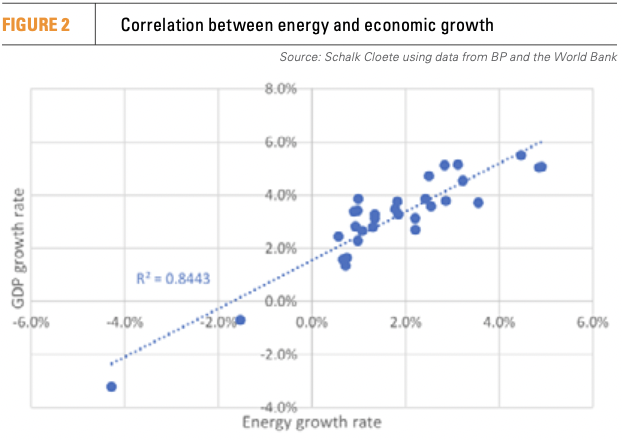

The rapid global economic development required “to uplift the 86% of the world population currently living below $1,000/month (see figure 2) is inextricably linked to continued growth in an abundant supply of affordable energy.”

In addition to taking measures to accelerate energy transition, an increase in global oil and gas production is an important step in this process.

It is interesting to note that high gas prices are leading to a rebound in coal-fired power, even as the EU and US are pushing for an accelerated energy transition. Expensive gas is leading to more coal.

Bloomberg states that “Ignoring the transition means embracing a descent into an increasingly unstable climate. That’s something our modern society has very limited experience with — but what we do know is dire.” However, it is not a case of ignoring transition. It is a case of achieving transition in an orderly, reliable and affordable manner. Divesting from oil and gas prematurely and while renewables are not ready to fill the gap, will not achieve that. As Sultan Al Jaber, chairman ADNOC, said, “We cannot and must not unplug the current energy system before we have built the new one.” Oil and gas have a key role to play in this process.

Bloomberg states that “Ignoring the transition means embracing a descent into an increasingly unstable climate. That’s something our modern society has very limited experience with — but what we do know is dire.” However, it is not a case of ignoring transition. It is a case of achieving transition in an orderly, reliable and affordable manner. Divesting from oil and gas prematurely and while renewables are not ready to fill the gap, will not achieve that. As Sultan Al Jaber, chairman ADNOC, said, “We cannot and must not unplug the current energy system before we have built the new one.” Oil and gas have a key role to play in this process.

SOURCE FOR GRAPHICS

Figure 1: Worldwide upstream spending 2010 to now

Figure 2: Correlation between energy and economic growth

SOURCE:Schalk Cloete using data from BP and the World Bank