Vietnam’s new power plan provides (some) clarity for LNG [Gas in Transition]

The release of Vietnam’s Eighth Power Development Plan (PDP8) in May was greeted with considerable enthusiasm by local and international industry players. This was unsurprising – the long-awaited and frequently-revised plan finally offers some certainty about the medium-term prospects for LNG and other energy sources in Vietnam.

PDP8 was followed by publication on July 26 of the national energy master plan for 2021-2030. The master plan is in large part shaped by the PDP, since the power sector accounts for a large part of commercial energy use in the country.

PDP8 provides detailed projections to 2030 and a vision towards 2050, and replaces PDP7, which was issued in 2016. Originally due to be published in 2021, PDP8 was delayed to accommodate radical changes in government energy policy.

Major shift from coal to benefit LNG

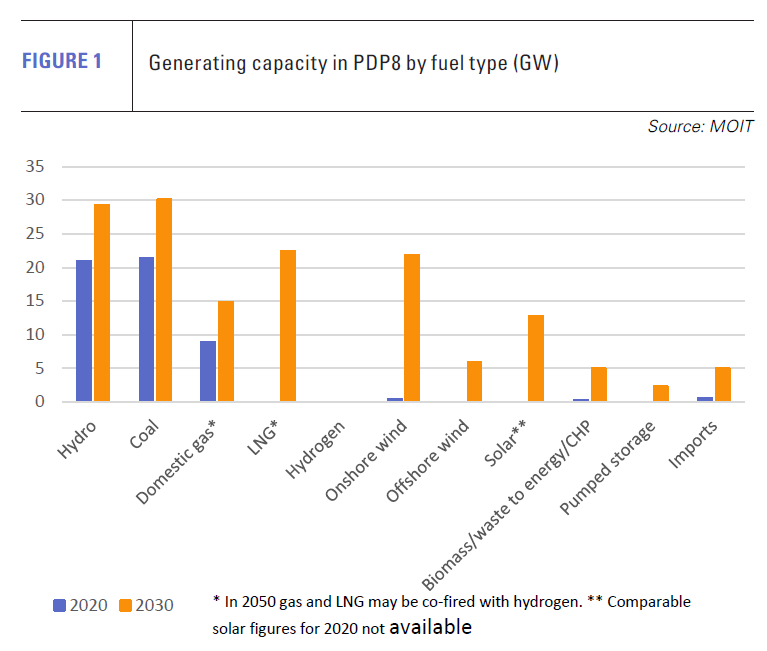

PDP8 sees a dramatic shift from coal to renewable energy and gas (see figure 1), both to help meet Vietnam’s commitment to reach net zero by 2050 and improve energy security.

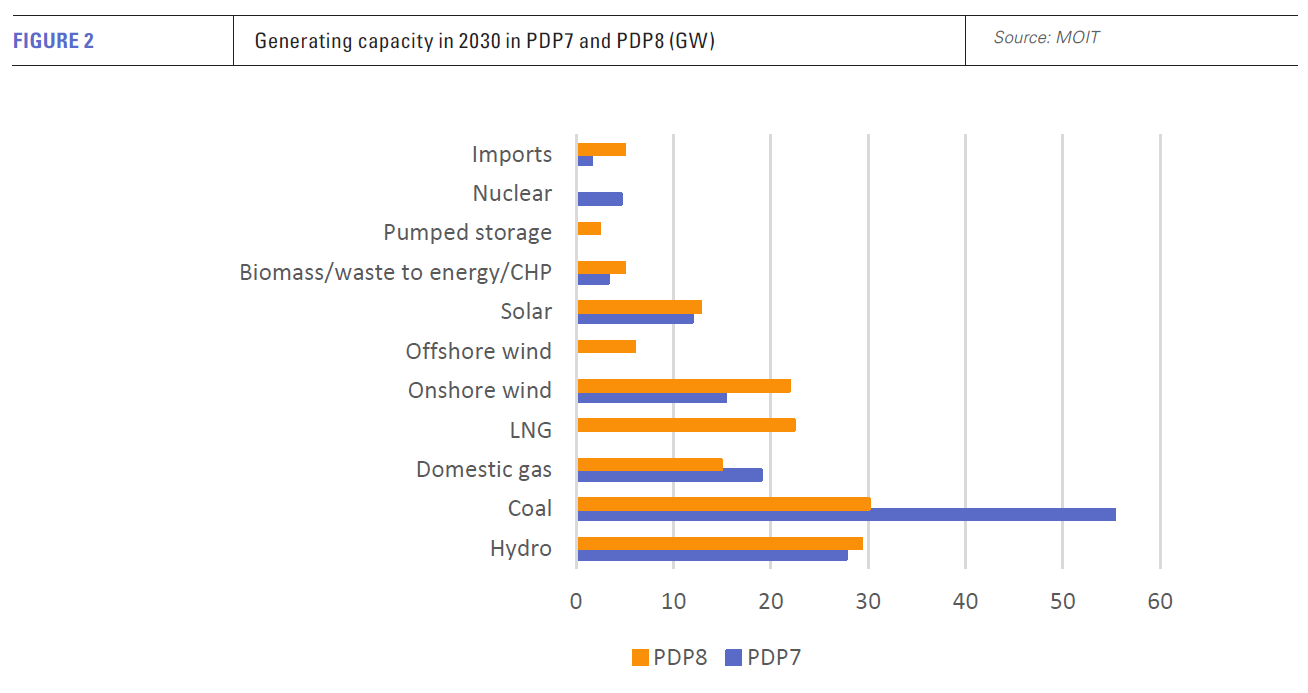

PDP7 had envisaged that coal-fired generating capacity would increase to 55.3 GW in 2030 (see figure 2), or about two-fifths of the 138.8 GW of total capacity projected as then operating. Wind and solar plants would together account for 27.3 GW, hydroelectric facilities 27.8 GW, nuclear reactors 4.6 GW and gas-fired capacity a modest 19 GW, with the plants fuelled by domestic gas.

By contrast, PDP8 sees coal-fired capacity increasing only to 30.1 GW in 2030. This represents a fifth of the 150.5 GW of total capacity now projected as needed by 2030, based on economic growth of 7%/year from 2021. Wind and solar capacity is projected to total just over 40 GW, with hydroelectric capacity remaining much the same as in the previous plan at 29.35 GW. Nuclear power has dropped out of the picture.

As a result, the main beneficiary is gas and in particular LNG. Gas-fired capacity is forecast to reach 37.3 GW in 2030. Domestic gas is projected to fire 14.9 GW of the capacity, with LNG fuelling the rest. The 22.4 GW of LNG-fired capacity comprises 13 plants, with two more plants with 3 GW of capacity scheduled to enter operation between 2030 and 2035.

Increased LNG use to precede renewables growth

However, gas’s role is intended to be transitional. The four-fold increase in gas-fired capacity from about 9 GW in 2020 will come ahead of a full-blown switch to renewable energy. By 2050, wind and solar capacity is projected to total at least 130 GW and 169 GW, respectively. In the same year, it is projected that coal-fired generation will have been eliminated, while the amount of gas-fired capacity will fall and much of what remains will be co-fired with hydrogen.

That said, the medium-term prospects for gas and LNG are very positive, if the PDP8 capacity projections are achieved. That, however, is a big ‘if’.

Signs of progress

The release of PDP8 coincided with the announcement of progress on several initiatives.

Most notably, on July 10, Vietnam imported its first cargo of LNG, with the fuel being supplied by Shell to the Thi Vai import terminal in Ba Ria-Vung Tau province. The country’s first regasification facility, Thi Vai is operated by the state-owned PetroVietnam Gas (PV Gas), currently the country’s sole licensed LNG importer.

That was followed on July 11 by a joint venture between the US’s AES and PV Gas securing investment approval for the 3.6mn tonne/yr Son My import terminal in Binh Thuan province. On its scheduled entry into service in 2027, the terminal will supply LNG to AES’s 2.2-GW Son My-2 CCGT project, which has already secured investment approval.

Elsewhere, the Korea Export-Import Bank signed an initial agreement in late June to help finance 3 GW of LNG-fired capacity in Long An province being developed by local company Vina Capital and GS Energy. Local and South Korean companies, including T&T Group, Hanwha Energy, Korea Gas and Korea Southern Power, are separately developing a 1.5-GW project and LNG import terminal at Hai Lang in Quang Tri province for operation by 2027.

And, in August, a delegation from Thailand’s Gulf Energy Development visited officials from Thanh Hoa province to advance plans to implement an LNG terminal and power plant at Nghi Son.

LNG fills the gap

The release of PDP8 has thus produced a spurt of activity. But question marks remain over the medium-term gas projections, both in terms of the availability of the gas and the infrastructure needed to deliver and use it.

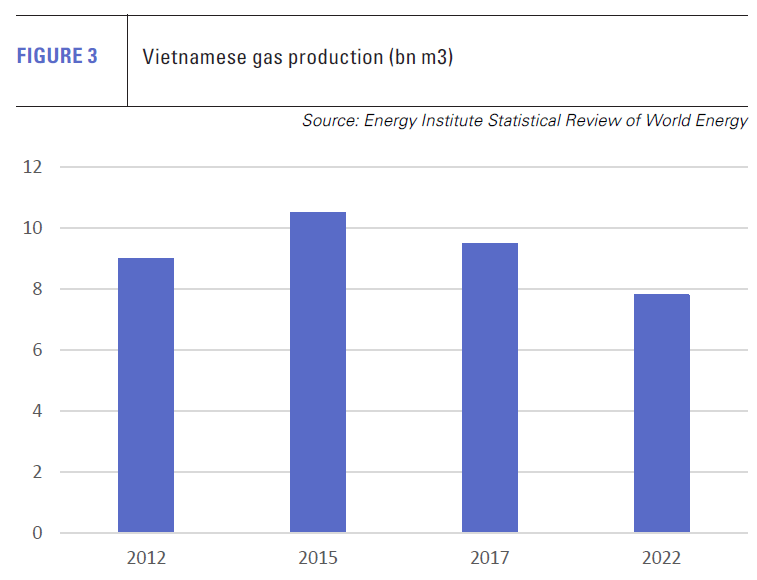

Total gas requirements are projected to rise from 8.1bn m3 in 2022 to 30.7-33.2bn m3 in 2030. Domestic gas supply in 2030 is projected at up to 15bn m3. However, production has fallen in recent years to 7.8bn m3 in 2022 (see figure 3), and achieving 15bn m3 depends on the 6.4bn m3/yr Block B entering operation from 2027 and the 9bn m3/yr Ca Voi Xanh project starting operation in 2030.

Should the two projects enter service on schedule, LNG requirements in 2030 would be 15.7bn m3. But both Block B and Ca Voi Xanh have been under development for a decade and face a range of political, technical and financing issues. Further slippage in their development could result in 18.2bn m3 of LNG or more being required by 2030.

This would necessitate considerable investment in LNG import capacity, with more than 13mn t/yr (17.7bn t/yr) required.

Thi Vai’s 1mn t/yr of capacity is due to increase to 3mn t/yr from 2025, while the first phase of Son My is due for completion by 2027. Other projects are in the pipeline, including a 0.5mn t/yr Floating Storage and Regasification Unit and a 3mn t/yr land-based project in Haiphong, and the 3mn t/yr My Giang project in Khanh Hoa. However, some of this capacity is not expected to enter service until 2030 or after.

Bringing forward this capacity would only be worthwhile, if investment in LNG-fired generating plants gathers momentum. Some of the 13 named projects in PDP8, such as AES’s Son My-2 and PV Power’s Nhon Trach-3/4 project in Dong Nai, have made significant progress, but most remain at an early stage of development.

Bankability in question

While the switch in emphasis to LNG-fired generation is relatively recent, there are more basic reasons for the slow progress. Many of these apply equally to other types of power plant and to Vietnamese infrastructure projects in general, and most involve long-standing issues.

A key issue is that government policy is subject to sudden and at times arbitrary change. Another is that the country’s legal and regulatory framework is complex and in parts opaque. The rules on the selection of investors and on who is responsible for the award of permits, and under what conditions and timescales, are among the issues often involving uncertainty.

One key issue specific to the electricity sector is that the state-owned Electricity of Vietnam (EVN) does not offer a standard power purchase agreement. Nor do the PPAs it does offer incorporate the volumes and pricing structure (including fuel cost pass through) needed to make the projects bankable for commercial lenders.

EVN’s unwillingness to offer these terms reflects the fact that Vietnam’s retail electricity prices are state controlled and not cost-reflective. This means EVN cannot automatically pass through changing fuel costs. EVN’s resultant uncertain financial status means that international investors and lenders seek sovereign guarantees to underpin the PPAs, and want the involvement of multilateral or bilateral lenders in the financing group to give it more clout.

Future proofing projects is also problematic given the planned, but imprecise, future liberalisation of the Vietnamese electricity market.

LNG terminals and other projects face similar problems. None are insoluble, but working through the issues takes a substantial amount of time. That, combined with the limited number of bilateral and multilateral agencies whose backing is essential to make projects bankable, suggests not all – or even most – of the 13 LNG-fired generators will be built by 2030. It follows that the amount of LNG terminal capacity may also be lower than projected in PDP8.

Development issues common across energy sources

However, it should be noted that the other energy sources prioritised in PDP8 face similar, if not worse logistical and financing issues. This suggests that the large amount of solar and wind capacity planned will also be difficult to achieve.

In addition, the proposed construction of several capital-intensive coal-fired plants – the operating life of which will be much shorter than their design capacity -- seems likely to face problems securing finance, while bringing online the Block B and Ca Voi Xanh gas fields by the end of the decade is also very optimistic.

All of which means LNG cannot be dispensed with, if PDP8 is to be anywhere near achieved. While not all the LNG terminals and associated generating plants may be financed and built, Vietnam is thus still likely to become a significant LNG importer by the end of the decade.

While it is difficult to assess which LNG projects will succeed and which fall by the wayside, it seems likely that projects in which the terminal and power generator are integrally linked – particularly by sharing a location and investors – could be the most likely to succeed.