Vaca Muerta: a dead cow on a slow roast [Gas in Transition]

When US shale burst onto the oil and gas scene in the 2010s, drillers immediately began to assess the international potential for identikit industries elsewhere.

The US Energy Information Administration added data to the aspirations with a near global assessment of potential shale resources in its 2013 World Shale Gas and Oil Assessment. This suggested that shale could shake up gas production globally as multiple countries from Poland to South Africa had the potential to become major producers.

In practice, however, it has been hard to replicate the arguably unique combination of geological, political and economic conditions prevalent in the US. Almost a decade on and Canada and China are the only other big shale success stories, and, in China at least, shale, although a significant contributor to national gas production, has not delivered as much or as fast as originally anticipated.

Vaca Muerta

However, one of the biggest prospects continues to hold huge promise. Shale drillers have steadily been probing Argentina’s giant Vaca Muerta formation for just over a decade, building up the capacity to achieve industrial production.

The formation is estimated to be the second largest shale play in the world in terms of gas resource and the fourth largest for oil. It spans 30,000 km2, underlying much of Argentina’s Neuquén oil and gas basin and is three times the size of the US’ Permian Basin. It is home to multiple conventional oil and gas finds, including the large Loma La Lata gas field.

Shale exploration kicked off on Vaca Muerta with a small number of exploratory wells from 2009-2011 drilled by what was then Repsol-YPF. The Soil.x-1 well in 2011 was the first to specifically target the formation’s shale resource. The well was fractured five times and successfully produced hydrocarbons, a result heralded as a major breakthrough in the play’s development.

The basin’s prospects looked so promising and the potential resource so large that the resource nationalist government of Cristina Fernandez moved to expropriate Repsol’s share of the company, returning it to state control, a move which, many lawyers later, resulted in a $5 billion settlement.

YPF was quickly joined by big players such as Chevron, Total, Shell and ExxonMobil, which, having come late to the US shale scene, hoped this time to get in on the ground level. They were followed by a rush of smaller local companies, some of which were specifically gas rather than oil focussed.

Originally very limited, drilling services have expanded, with Halliburton and Schlumberger to the fore. From 2016, the drillers shifted from vertical to horizontal drilling. And, from 2018, high costs really started to fall and well productivity increase.

With almost a decade of experience, it is now estimated that the formation holds unconventional resources of 2.6 trillion m3 gas and 14.3bn barrels of oil.

There seems to be little doubt that, with sustained investment, Vaca Muerta could become a world class centre for oil and gas production, one which could transform Argentina’s gas balance and provide sufficient gas for both regional gas exports and LNG.

Investment risk

However, oil and gas production in Argentina has had a rocky path, not least because of changes in government that have seen energy policy swing back and forth from market-oriented reforms to resource nationalism. Governments in the early 2000s subsidised gas consumption, but without rewarding production, leading to a gradual decline from 2003 in what was then a gas surplus exported predominantly to Chile. By 2008, Argentina had become a net gas importer.

In addition to the expropriation of YPF, the country has also suffered recurrent debt crises in which governments have limited capital flows, making Argentina a high-risk and uncertain investment environment. Drillers have had to contend with limited infrastructure and an initial lack of drilling services and experienced staff, as well as negotiating Argentina’s well organised oil and gas unions.

However, production from the formation has gradually crept upward and it remains a focus of both YPF’s ambitions and some of the oil majors. Shell, for example, plans to invest $1 billion this year drilling around 100 new wells.

Rapid growth

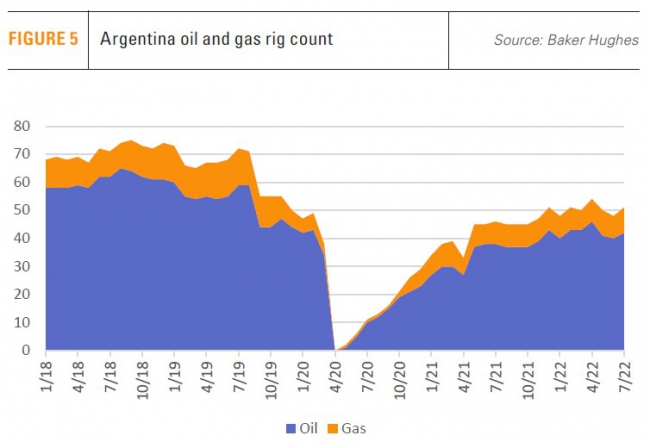

In September last year, consultants Rystad Energy identified the formation as being the world’s fastest growing shale play. Although there are fewer rigs in operation than in 2018, the basin’s producers are setting records for the number of new wells drilled, indicating that they have achieved factory mode production.

The upturn in drilling last year saw oil production exceed 160,000 b/d for the first time. Gross gas production leapt higher from April 2021 when it was just below 1bn ft3/d (28mn m3/d) to almost 1.6bn ft3/d (45mn m3/d) in August.

Rystad attributed the increases to large reductions in well costs since 2018, which have put Vaca Muerta wells on a par with those drilled in the Permian Basin. Well productivity on Vaca Muerta is often higher, but so too are costs, despite improvements, according to the drillers.

Rystad attributed the increases to large reductions in well costs since 2018, which have put Vaca Muerta wells on a par with those drilled in the Permian Basin. Well productivity on Vaca Muerta is often higher, but so too are costs, despite improvements, according to the drillers.

This year, YPF reported a 19.8% increase in natural gas production in the first quarter, year on year, to about 1.35bn ft3/d (38mn m3/d). Unconventional gas production jumped 140% from the year ago period, indicating that Vaca Muerta shale has become central to the company’s production profile.

YPF has announced a broadening of exploration this year to the northern section of the formation in Mendoza, while oil majors such as Chevron continue to acquire exploration concessions.

Last year, drillers reported 10,254 fracking stages on the shale play, compared with 3,276 in 2020 and 6,405 in 2019. YPF accounted for about half with Pan American Energy, which is 50% owned by UK oil major BP, and Shell being the second and third most active frackers respectively.

Vaca Muerta now accounts for about 38% of national oil output of 578,000 b/d and 32% of the country’s 127mn m3/d of gas production, according to Energy Secretariat data.

Evacuation bottleneck

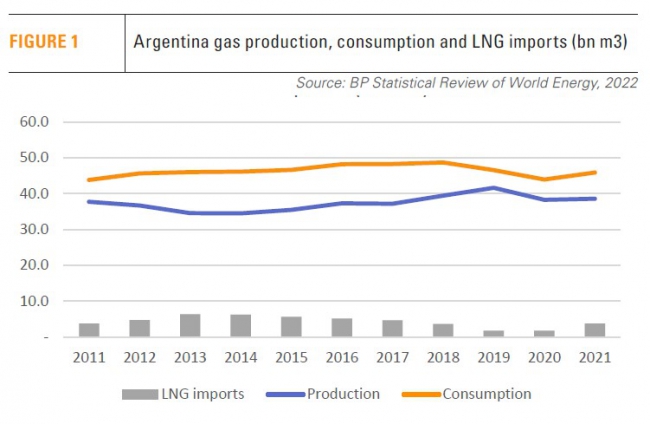

The current government has also committed to addressing one of the formation’s primary challenges – a lack of takeaway capacity. If more gas from the formation can be distributed more widely, it could start to displace the LNG and pipeline gas imports on which Argentina has come to depend, particularly when domestic demand is high in winter.

Without the prospect of gas reaching markets, domestic or foreign, upstream producers will not invest in additional production capacity.

In February, the government announced its support for the proposed 44mn m3/d President Nestor Kirchner gas pipeline, which would connect Vaca Muerta to the Buenos Aires area, raising evacuation capacity from the formation by 25%. Although already the subject of political controversy, the government hopes to see the pipeline completed by mid-to-late 2023.

President Alberto Fernandez issued a decree in February giving state energy company IEASA a 35-year concession for the pipeline, allowing the company to build, maintain and operate either directly or via third parties. It also establishes an administrative and financial vehicle for the project called Fondegas. The project will have two phases, with the first being supported with public funds at a cost of around $1.6bn.

The pipeline will be 563-km long, running from Tratayen to Saturno, Salliquelo and then San Jeronimo. A contract was signed in June with pipeline producer Tenaris for 582 km of 36-inch diameter pipe and 74 km of 30-inch pipe. However, Tenaris was the sole bidder and questions have been raised about the tender’s validity, resulting in a judicial review, which could in turn lead to delays.

Indeed, political infighting within the government and Argentina’s precarious financial position have led many commentators to conclude that the pipeline’s construction schedule will slip. Presidential elections are to be held in October 2023, adding another layer of political uncertainty, if the project is delayed.

Nonetheless, the government’s desire to promote investment in Vaca Muerta can also be seen from an easing of capital controls for energy companies.

An official decree published May 27 allows oil and gas companies that increase oil and gas production this year to access US dollars at the official exchange rate for a limited period, which allows them to repay debt, repatriate direct investment and pay dividends.

But, as with the politics surrounding the pipeline project, investors will be wary of the potential for future adverse policy changes concerning capital controls and the wider investment environment. Policy consistency has been and remains a major investor concern in the country.

LNG exports and imports

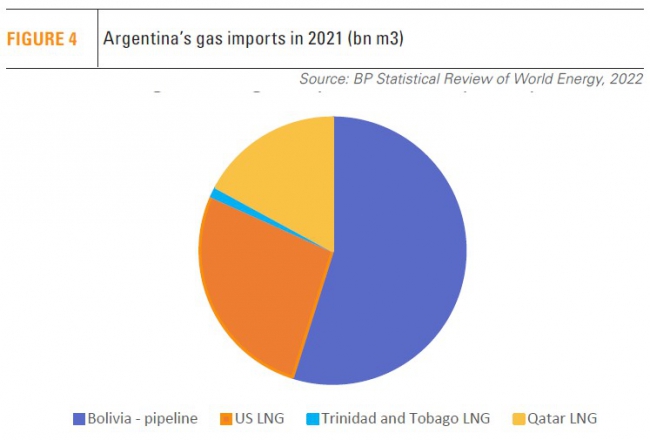

From an initial 0.4bn m3 in 2008, Argentine LNG imports rose to a peak of 6.3bn m3 in 2013, before declining to 1.8bn m3 in both 2019 and 2020, primarily to cover winter demand. However, imports rose again last year to reach 3.7bn m3 and demand has again been high during a cold southern hemisphere winter. Last year, LNG and pipeline imports totalled 22.6mn m3/d.

In combination with steeply rising LNG prices from the second half of last year, Argentina now faces a big bill for its gas balancing costs through imports. It has managed to increase gas imports by pipeline from Bolivia -- at the expense of flows to Brazil -- but it still needs LNG to balance supply with demand.

LNG prices rose steeply in the latter half of last year and have received a further boost from hugely increased European demand, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Europe is expected to absorb all of the new liquefaction capacity coming onstream this year. Given the lead times for LNG capacity and the speed with which European countries are moving to put regasification facilities in place, European demand seems likely to keep LNG prices high in coming years.

This is affecting LNG importers worldwide and Argentina is no exception. As a result, boosting domestic gas production would have immediate benefits in terms of reducing expensive LNG imports. More tantalizing still, it holds out the prospect of joining the market as a producer, allowing Argentinean gas producers to cash in on high LNG prices.

Liquefaction plans

In 2019, Argentina exported its first LNG cargoes via a small-scale Floating LNG production vessel. YPF chartered the ship from Belgium’s Exmar, but cancelled the 10-year lease in 2020 as LNG prices slumped and domestic gas shortages increased.

Although the country has yet to fully meet domestic demand, LNG export plans are being revived based on higher production from Vaca Muerta and the proposed new pipeline. Moreover, the shift in demand from Asia to Europe should benefit Argentina as a would-be Atlantic basin LNG producer.

YPF chairman Pablo Gonzalez in May said the company was looking at three or four potential locations in the provinces of Buenos Aries and Rio Negro to site an onshore liquefaction plant. The plan is for an $11.5bn investment, including upstream drilling and a feeder pipeline.

Both the Interior Minister Eduardo de Pedro and Economy Minister Martin Guzman have also said they are considering plans for investment in LNG export capacity.

Although 2026 has been mooted as a potential start-up date, none of the proposals have identified a specific site or put finance in place. Backers may be hard to find given Argentina’s volatile investment environment and the potential for adverse policy developments not just in development but over the longer-term operation of the plant.

Nonetheless, big players have important stakes in Vaca Muerta and see it as a potential growth area. Although YPF, which is 51% controlled by the state, appears likely to take the lead, others may join if sufficient investment certainty can be guaranteed. With new takeaway capacity in the planning, Vaca Muerta’s giant shale resources may finally start to make a permanent impact on the global LNG scene.

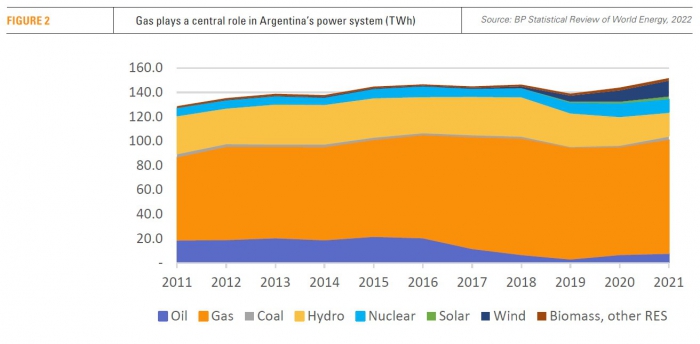

Gas-fired generation is Argentina’s primary source of power

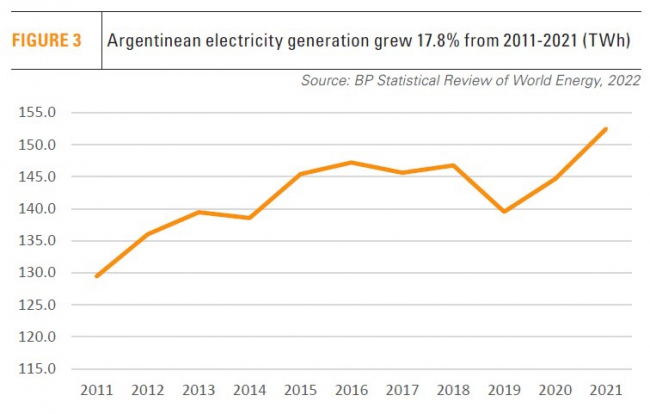

Gas-fired electricity generation has steadily grown in importance for Argentina, last year accounting for 62% of total power generation, up from 53% in 2011.

Nuclear generation has increased since 2018, when the refurbished reactor at Embalse came back on line, and new construction is planned. In February, an engineering, procurement and construction contract was signed with China’s CNNC for what would be the country’s fourth reactor. China is expected to provide the majority of the project finance.

Renewable energy generation from wind and solar is also rising and now makes a small but important contribution to national electricity supply, one which is expected to expand significantly over the next decade.

However, hydroelectric generation has varied considerably. In 2011, hydro generated 31.2 TWh of electricity, but, in 2021, only 19.6 TWh. Despite the increases in nuclear and renewables, gas-fired generation, and gas imports, were needed to fill the gap.