US shale oil, gas production poised for decline [Gas in Transition]

A recently completed study by US data analytics firm Enverus concluded that US shale oil and gas production is dropping “faster than expected.” Given its far-reaching implications, this attracted considerable attention. In effect, the study states that after doubling production during the past decade, the shale industry is unlikely to see any more surges in future.

Enverus went further, stating that “shale’s future production growth is expected to be more difficult.” Dane Gregoris, managing director Enverus Intelligence Research (EIR), added that “the US shale industry has been massively successful, roughly doubling the production out of the average oil well over the last decade, but that trend has slowed in recent years” – it has become a memory. In fact, Rystad Energy estimates that last year, for the first time, the average volume of oil produced from each new well was down on the year before.

Grigoris went on to say that “we have observed that production-decline curves, meaning the rate at which production falls over time, are getting steeper as well-density increases. Summed up, the industry’s treadmill is speeding up and this will make production growth more difficult than it was in the past.” Enverus expects these curves to continue to steepen over time as basins get more densely developed, making well production-decline faster. As a result, average breakeven prices will rise.

This has also been confirmed by the Energy Information Administration (EIA) in its latest Drilling Productivity Report. It states that new well oil production per rig in the Permian, the most prolific shale basin, has dipped considerably over the last few years. It expects production to fall in other regions too.

With US shale production accounting for most of the non-OPEC oil supply growth, any slowdown could have wider global implications.

Difficult but not over

Well production decline may be getting faster, but that does not mean that shale production is about to start going down immediately.

It is slowing down but there is no end in sight yet. However, ConocoPhillips CEO Ryan Lance said in April “you see the plateau on the horizon.” Others in the oil and gas industry have also been cautioning against expectations of much higher shale production, warning that cost inflation is making a lot of wells uneconomical.

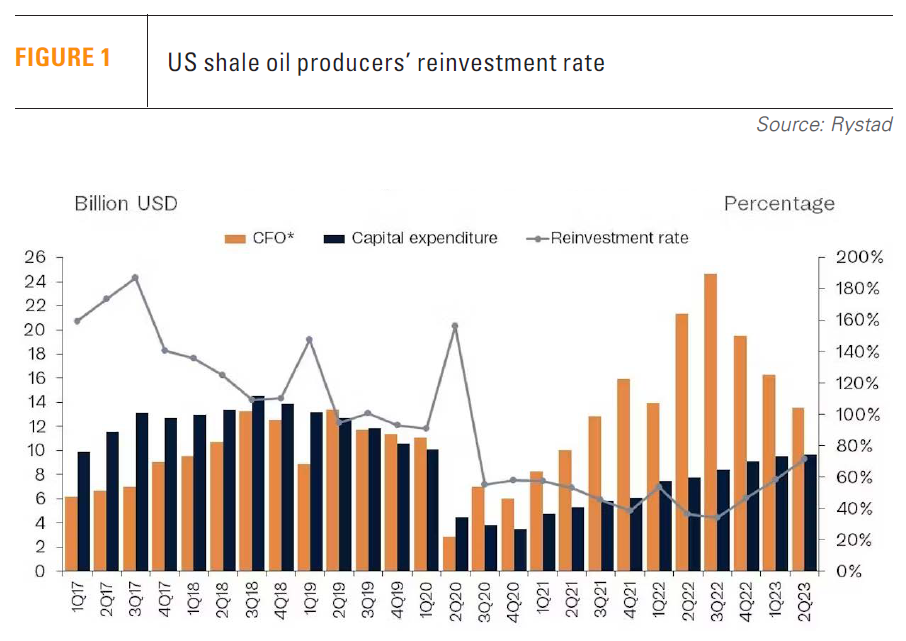

BNEF identified three reasons for this: “declining productivity of wells, the conservative investment strategy of producers amid a shift in focus to capital discipline, and the rising cost of oilfield services.” Structural underinvestment is a key factor (see figure 1).

The shale reinvestment rate, defined as is the ratio between capital expenditure and cash flow from operations (CFO), slowed down during COVID-19 period, but picked up in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But, according to Rystad, with Inflation pushing up drilling and completion costs and contributing to a rise in capital expenditure, labour shortages and the new era of capital discipline, this will be slowing down. Enverus said wells cost 30% more to drill in 2022 than in 2021 and expects the price to go up another 12% in 2023. Despite these higher costs, capital expenditure has levelled off at about 70% of its 2018 peak, a clear indication that activity is declining.

But even with inflation easing and oil prices going up, Rystad does not expect a change of strategy. As a result, growth will be difficult.

Enverus points to another challenge, that most of the land is already owned or leased, offering few opportunities to drill new areas with sizable oil and gas reserves. As the Washington Post points out, “the best drilling sites have already been tapped. New drilling is moving into more difficult or expensive sites.”

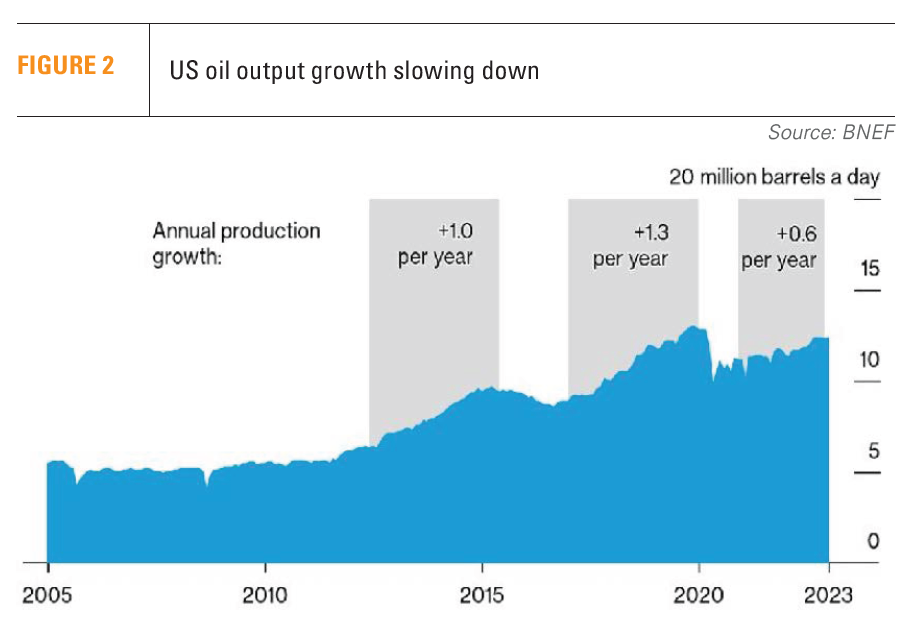

According to BNEF, oil production in the US increased by 1.3mn barrels/day per year during the boom period 2017 to 2020, but this growth halved to 0.6mn bls/day in 2021 and 2022 (see figure 2). EIA estimates growth next year to be even slower, at less than 0.2mn b/d.

According to BNEF, oil production in the US increased by 1.3mn barrels/day per year during the boom period 2017 to 2020, but this growth halved to 0.6mn bls/day in 2021 and 2022 (see figure 2). EIA estimates growth next year to be even slower, at less than 0.2mn b/d.

One of the concerns is that this slowing momentum means it will be challenging for the US to continue playing “a major role in the evolving global crude oil and products trade as Europe looks for alternatives to Russian supplies.”

Like oil, natural gas production benefited from the high prices during the second half of 2022. But by the summer this year it slumped to less than $2.50 per mn btu. Gas production growth is expected to slow sharply in the second half of 2023 and into 2024.

But the problem with natural gas is that in the US, while gas provides steady cash flow, it is worth less than oil, even in periods when the value of gas is not as depressed as it is now.

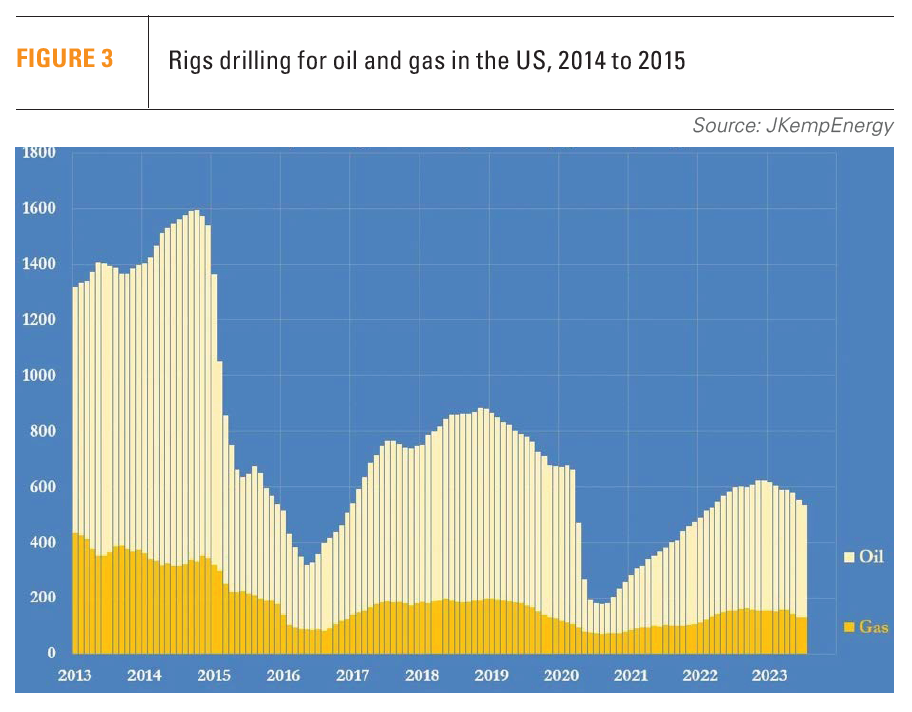

Another indication of this slowing down trend is the notable decrease in drilling rigs for shale oil and gas. At the beginning of the year, about 800 rigs were in operation, but that number now dropped to about 590 by mid-August. These numbers are significantly lower than the 888 recorded in 2018 and the high point of 1,609 rigs in 2014. Admittedly productivity improved, but the rig count trend is definitely downwards (see figure 3).

Analysts expect these challenges to continue. If capital investments remain stagnant and, with Inflation pushing drilling and completion costs escalating - forcing break-even costs up, companies cannot even maintain activity at a steady level, let alone expand operations. Oil and gas prices need to rise and stay high over long periods, to at least $80/b and $3/mn Btu respectively, for the US shale industry to maintain a high level of drilling activity. With the average oil price over the last five years at about $70/bl, this is a challenge.

This slow-down is business reality, literally. After a long period between 2010 and 2020 of recovering only about 50% of invested capital, following recovery from the pandemic the industry has been under increasing pressure from stakeholders and banks to make and return profits on these investments. Growth over profit is no longer acceptable. Dividends and share buybacks have now become the norm. That’s why re-investments rates have dropped dramatically.

As the FT pointed out in an article earlier this year, investors are benefiting from this drillers’ capital restraint and are “wary of making more risky bets on a sector with a bad record and an uncertain future in a decarbonising world.”

Energy transition concerns

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is accelerating energy transition in the US. It aims to make fossil fuels as clean as possible. It is imposing a charge of $900/t of methane emissions in 2024, increasing to $1,500 after two years, and it is offering tax credits for carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS). And all of this, while pushing for more renewables as fast as possible.

In addition, as a result of the IRA, the US is undergoing a shift away from fossil fuels as new battery factories, wind and solar projects, and other low-carbon investments increase rapidly across the country. The IRA could end up becoming even more effective at reducing fossil fuel emissions than the Biden administration expected.

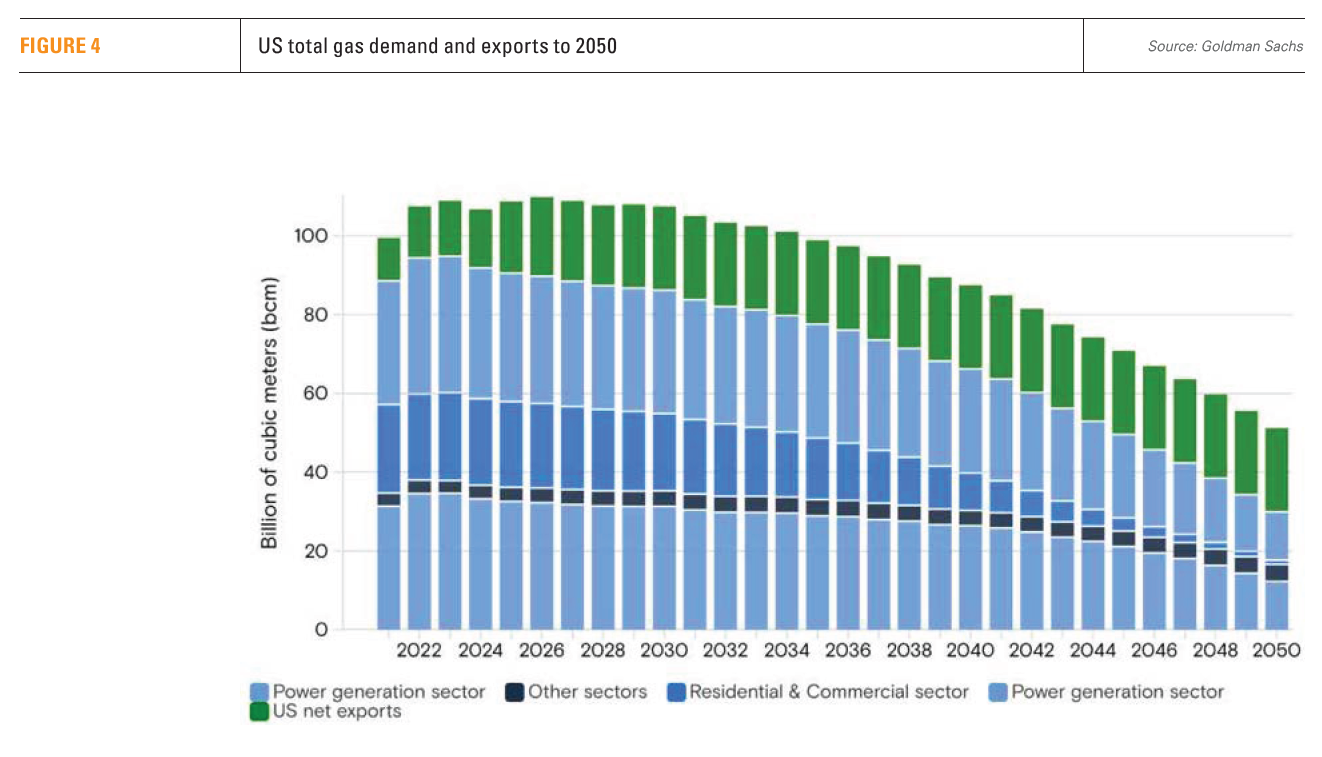

Goldman Sachs expects that as a result of the energy transition and the impact of the IRA, demand for natural gas will diminish in the US after 2030 (see figure 4). Between now and then it may grow, but only because of LNG exports.

It predicts that among residential and commercial users, over time electricity will gradually almost completely replace natural gas.

However, because renewable energy sources such as wind and solar still face major intermittency challenges and lack sufficient infrastructure, until this problem is resolved, natural gas, which generates much less emissions than coal, will have a role to play. At least in the short to medium term, natural gas can help reduce US carbon emissions by substituting coal in power generation.