Ukraine: Gazprom’s Key to Flexibility [NGW Magazine]

NGW sat down with Danila Bokharev, a senior fellow at the EastWest Institute who specialises in Eurasia energy and natural resource issues, during the European Gas Conference in January.

NGW took the opportunity to explore the expectations and reality concerning gas transit through Ukraine after 2019; the factors complicating negotiations; the impact of forthcoming elections; and the likely outcome. NB: the opinions expressed in this article solely reflect the views of the author, not the EastWest Institute.

NGW: What are the market players' expectations for gas transit through Ukraine?

Last year, Gazprom – the most important user of Ukraine’s gas transportation system (GTS) - expected transit to reach a maximum of 15bn m³/yr. In April, Russian news agency Ria Novosti quoted Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller stating: “We have never raised an issue about abandoning Ukrainian transit… a certain transit could still be in place in the amount of 10bn-15bn m³/yr, but the Ukrainian side has to explain the viability of the new transit contract.”

Analysts and market observers believe Gazprom should book larger volumes.

IHS Markit’s report “European natural gas – The new configuration,” published in April 2018, estimates transit of Russian gas through Ukraine will fall to 28bn m³/yr in 2020 and 22bn m³/yr by 2025. IHS Markit also foresees steady growth of transit volumes after 2025 that “cannot be achieved through non-Ukrainian transit routes alone” – 28bn m³/yr by 2030 and 43bn m³/yr by 2035.

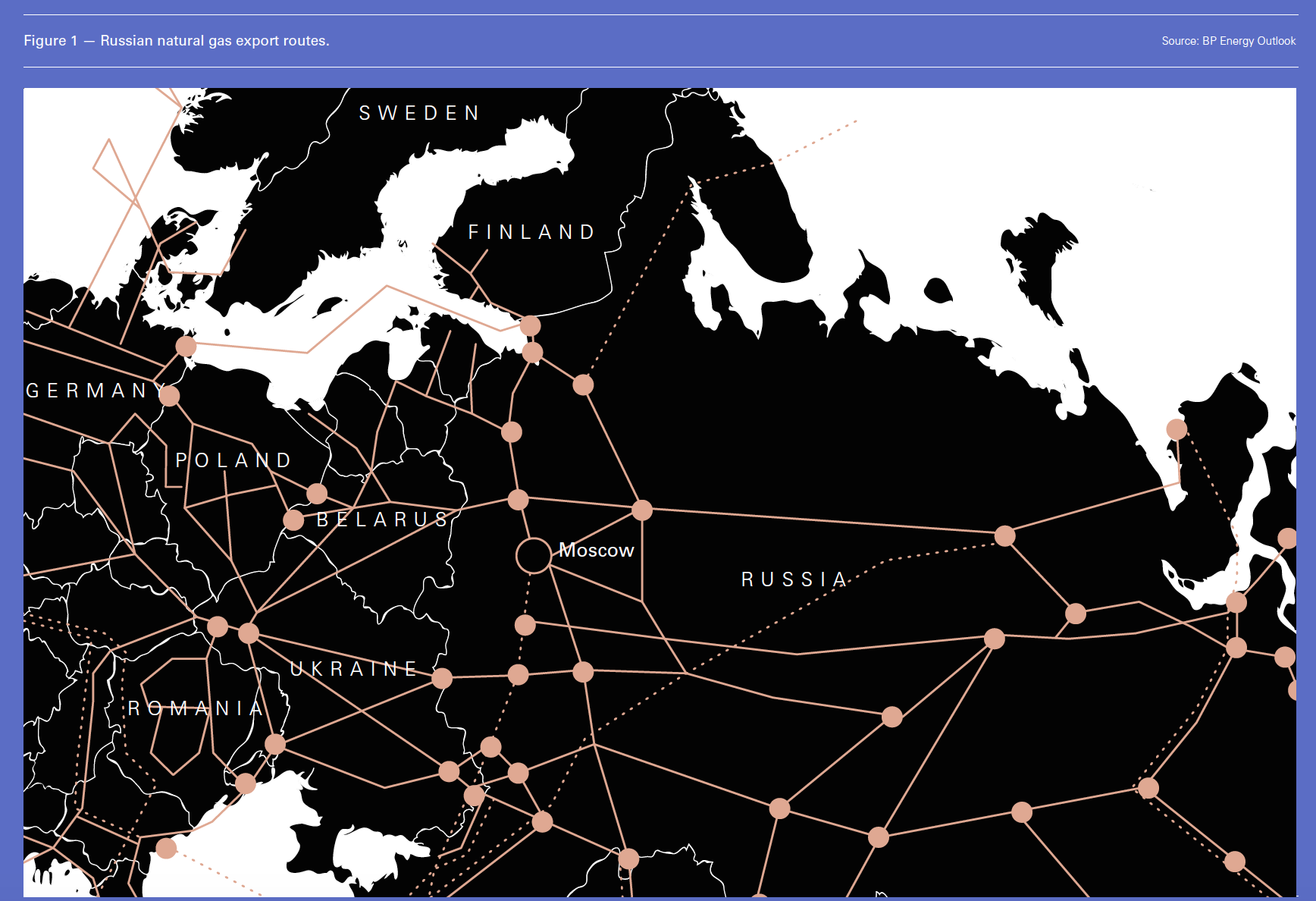

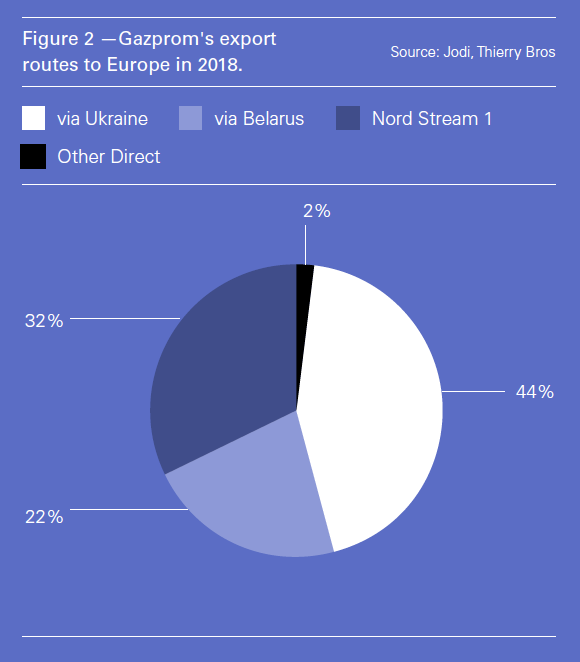

The IHS Markit report also envisages a ‘low LNG’ scenario with “greater LNG demand elsewhere in the world and/or lower global LNG supply, leading to much less LNG being available for the European market. This results in stronger demand for pipeline gas – including from Russia – and requires significant use of all main export routes (Figure 1) including the Nord Stream 2 (NS 2) pipeline and Ukrainian transit (Figure 2), to meet European requirements.

It means that the higher call on the Ukraine route might materialise even earlier than 2030. Roland Goetz from German think-tank SWP estimates the level of transit at 30bn-40bn m³/yr, while Jack Sharples from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES) said that transit in volumes greater than 26bn m³/yr will depend “on the European Commission (EC) and European gas importers, and their insistence that gas transit via Ukraine continues.”

NGW: Why does the Ukraine route still matter, even after Nord Stream 2?

The Ukraine transit route is the only corridor offering transit volume flexibility for Gazprom exports to Europe. The IHS Markit report stressed the fact that “the flow of gas through Ukraine would play an important role in meeting peak European demand at times of high seasonal requirements… Ukrainian transit volumes are then seen to recover in the mid-2020s as Europe’s indigenous production continues its decline.”

Jack Sharples rightly pointed out that Ukraine is the “only transit route with spare capacity in times of peak winter demand”. For example, the Isaccea interconnection point for the TransBalkan pipeline was flowing at above 80% of capacity from October 30, 2017 to February 24, 2018. “With Blue Stream fully loaded, Isaccea provided seasonal flexibility for Russian gas supplies to Turkey in line with seasonal Turkish demand.”

Obviously, construction of the Turk Stream pipeline will resolve this issue, but not the issue of access to the daily flexibility, pipeline maintenance and increased demand for Russian gas in Europe.

Transportation capacity is not just about annual capacity; daily flows matter as well. Peak demand can be significantly higher than daily flows during low demand periods. Furthermore, pipelines occasionally undergo maintenance thus creating additional demand for Ukraine’s ‘spare capacity.’

NGW: Can you comment on the condition of the Ukrainian transit system?

Currently only the Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhgorod (UPU) pipeline (Figure 1), with a capacity of some 30bn m³/yr, is being refurbished, whereas it is unclear that any other major segments will be modernised soon owing to a lack of financing. Naftogaz recognises the need to adjust Ukrainian gas infrastructure to the new realities while keeping investments at the relatively low level.

Speaking at the 14th Yalta European Strategy Annual Meeting, Naftogaz CEO Andriy Kobolev said: “Until I see clarity after 2019, I will be restricting my investment to maintain proper levels. I will replace what will definitely be working for domestic transportation, but I will be very careful with transit. We are losing the sales line. TurkStream is a done deal. It’s going to be there, whatever we do here. Which means our sales line will die.”

Furthermore, the Naftogaz investment strategy prioritises upstream over transportation. In October last year Naftogaz announced an investment programme for 2019 in which it plans to invest hryvnia 34.5bn ($1.27bn) in upstream, and only hryvnia 7.3bn in gas transportation. This shows that Naftogaz does not really expect full-scale use of Ukraine’s gas transportation system in the near future.

NGW: Can you comment on Ukraine’s expectations verses reality?

While Ukraine’s general interest is clear – to guarantee ‘transit rent’ of around $2bn-$3bn/yr regardless of the shipped volume – Kiev hardly speaks with one voice. The lack of a common position is partly explained by an internal political struggle.

In April 2018, Igor Nasalik, Ukraine’s energy minister said: “Transit below 40bn m³/yr is not justified from an economic point of view.” In July 2018, Oksana Ishchuk, an analyst at Ukrainian think-tank Centre for Global Studies Strategy XXIstated that the Ukrainain GTS is only profitable when flows exceed 60bn m³/yr.

Last summer, Naftogaz proposed changing the transit to 141bn m³/yr, in case there were a substantial rise in ship-or-pay commitments. This is the most radical and the least realistic assessment of the future transit capacity of Ukrainian pipeline system, which is not even supported by the investment strategy of Naftogaz for the coming years. If the company’s investment strategy does not change, it will be difficult to count on more than 30bn-60bn m³/yr of technically guaranteed transit capacity in Ukraine from 2030-35.

NGW: What is the reasoning behind the transit numbers produced by the Ukrainian side and the European Commission (EC)?

Recently RadioFreeEurope/Radio Liberty reported that the EC proposed that Russia and Ukraine should conclude a 10-year transit contract with a 60bn m³/yr ship-or-pay clause and the possibility of shipping additional flexible volumes of up to 30bn m³/yr.

These volumes are totally unrealistic, disconnected from market realities and are purely politically motivated. It seems these numbers are produced to boost Ukraine’s negotiating position and to please voters in Slovakia who are obviously concerned about the future of gas flows transiting Ukraine and Slovakia.

NGW: What are the factors complicating transit negotiations?

Negotiations are complicated by several factors such as an ongoing debate on the results of the Stockholm Arbitration, Ukraine’s presidential elections, European elections and elections in Slovakia, which is a transit country for Russian gas passing through Ukraine and the transition of power between the old and the new EC.

Furthermore,Russia and Ukraine have opposite views on the future of the transit arrangement. Russia's permanent representative to the EU Vladimir Chizhov said in an interview with TASS in January that Russia considers the contract for gas transit through Ukraine to be valid until the end of 2019, and that it will be ready to extend it for a long time, perhaps for another 10 years. The Russian side did not specify the volumes to be transited within this renewed contract. In fact, the wording of the transit contract allows flexibility in transit volumes.

Naftogaz however prefers a new contract based on ‘European rules’. Naftogaz COO Yuri Vitrenko said in a Facebook post that Naftogaz will try to seize Gazprom’s assets in Europe. He said the decisions are now subject to urgent enforcement, as indicated by the decision of the Court of Appeal in Sweden, which states that the appeal of arbitration awards does not relieve the losers of the need to comply with them or suspend or delay implementation of these decisions.

NGW: What would be pre-condition for a mutually acceptable deal?

This would require a political will to sign at least a temporary agreement and readiness to then agree to a market-based transit contract.

NGW: Do you see other actors such as Germany getting involved in the EC's absence during summer/early autumn?

Since the return of the EC vice-president Maros Sefcovic from his ‘electoral leave’ is not guaranteed – he might be elected president of Slovakia by then – Germany could become the new negotiator and its involvement might be beneficial in progressing the negotiations.

Germany’s minister for the economy Peter Altmaier visited Kiev and Moscow last year to kick-start the negotiation process. If Germany’s involvement is accepted by both parties, it would prevent negotiations ending up in stalemate.

NGW: How will Ukrainian and European elections affect the negotiations?

It is virtually impossible to negotiate before knowing the results of Ukraine’s presidential elections and the appointment of a new head of Naftogaz. These may create additional uncertainty at least until early May.

The transfer of powers from the old to the new EC will certainly lead to an absence of the EU negotiator – unless replaced by Germany – in the trilateral talks.

NGW: What is the impact of the legal disputes? What would be a realistic resolution?

Obviously, legal disputes and Naftogaz’ attempts to seize Gazprom’s assets in Europe complicate already difficult relations between the two gas companies. In this context Prof. Jonathan Stern (OIES) rightly stressed that it is difficult to imagine “that it will be possible to establish a lasting transit agreement while Ukrainians are attempting to seize Gazprom assets and both sides are pursuing multiple (and increasing numbers of) arbitration cases against each other."

Gazprom sees this as the key challenge to relations. Last July, Miller said:“The main issue that predetermines the future relationship between Gazprom and Naftogaz [on transit] is the settlement of disputes and restoring the balance of interests under the existing contract.”

The issue of the arbitration award is also crucial for Naftogaz. The Ukrainian gas company sees it as a competitive advantage in transit negotiations. At this point, it is hard to say what is the realistic resolution of the legal dispute. It will depend on the outcome of Gazprom’s appeal, which could last for years.

However, both parties need to agree on at least a short-term transit deal before the end of the year, which means that both parties should find at least a partial temporary compromise to find a mutually acceptable and market-based solution. I believe there is a fairly strong possibility of a last minute temporary deal.

I do not see any significant problems with transit before December 2019. It is in no one’s interest to create problem for the stable flow of natural gas from Russia to Europe.

NGW: What happens if there is no deal? What is the impact on gas supplies to Europe?

Current political power games increase the risk of brinksmanship in the negotiation, which makes finding a solution more difficult. It is possible that negotiations will go the 11th hour, or beyond. No-deal could lead to a significant reduction in Gazprom’s physical gas deliveries to Europe after January 2020.

But since January 2009 gas crisis there has been a common feeling in the EU that the ongoing Ukraine crisis could have a negative impact on European gas supplies. As a result, measures to diversify and interconnect supplies have been implemented.

Europe’s relatively strong dependence on the Ukrainian route, which provides over 15% of EU-28 natural gas consumption was behind stress tests conducted by the EU gas transporters group Entsog in 2017. The Entsog study showed that the situation has significantly improved since 2009 and keeps improving every year.

For example, in case of a two-month long disruption of all gas imports to the EU via Ukraine in the winter period (January 1-February 28), gas infrastructure limitations would result in curtailment in only three member states: Bulgaria, Greece and Romania.

These countries would have to reduce their consumption respectively by 71%, 2% and 9%. Only Bulgaria will be seriously affected in case of a (theoretical) supply cut. But once the Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (IGB) is built, this issue will become irrelevant for Bulgaria as well.

Furthermore, the development of interconnectors between the EU member states means that central and eastern European (CEE) countries will be able to buy LNG and pipeline gas in the west and transport it to the east.

This purely theoretical situation could lead to an increased reliance on expensive LNG and a general increase in LNG prices in Europe and worldwide.

In this context, Europe might become a quasi ‘LNG island,’ with huge price spikes. For example, in January 2017, the price on France’s then LNG-dominated southern gas hub reached the equivalent of $600/’000 m³, while the Dutch gas hub price barely reached $350.

NGW: What would be a realistic deal for all the sides?

A realistic deal should reflect market realities, both in terms of transit fees and ship-or-pay volumes. Introduction of lower entry-exit tariffs by Ukraine’s energy regulator last December is definitely a positive step. However, this move should also be followed by a realistic market-based ship-or-pay offer.

Currently, it is difficult to speculate regarding the realistic parameters of a future agreement. Judging from information available from market players in January 2019, a realistic deal might be based on the new entry-exit tariffs, and an eight to ten-year contract with a 25bn-30bn m³/yr firm ship-or-pay commitment plus 40bn-60 bn m³/yr of flexible volumes.

Negotiations will be complex, but all sides being willing to accept market realities, a solution can be found.