What EU Policy Responses to the Ukraine Crisis Reveal About Energy Security Priorities

With Russia threatening to limit the flow of gas through Ukraine's pipelines, energy security has been pushed to the top of the European agenda. But between fracking East Sussex to insulating homes in Riga, policymakers can't seem to agree on the best course of action to secure Europe's energy supply.

We take a look at some proposals and assess if - and how - they contribute to Europe's energy security.

Defining energy security

But what is energy security? One reason there's a plethora of proposals is it doesn't mean just one thing.

Politicians have three aims when designing energy policy: ensure consistent supply, keep prices stable, and address climate change. If they misjudge their policies, any of those three could go awry and make the system insecure.

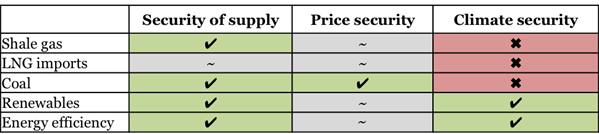

Some policymakers are keen for a like-for-like swap - replacing Russia's gas with imports from elsewhere. Others see the potential for a coal revival, or argue that investing in low carbon energy sources is the best plan. Each option could help secure Europe's energy future in a different way, as this table shows:

Alternative fossil fuels

One option is to explore shale deposits dotted around Europe and ramp up domestic oil and gas production. Britain's prime minister David Cameron even suggested the UK had a "duty" to get its fledgling shale gas industry up and running in the wake the Ukraine crisis.

But Europe's shale gas industry is still in its infancy and experts predict it could be at least five years before wells start flowing. Even then, the quantities are expected to be small compared to those extracted in the US. Furthermore, shale gas is traded on the international market and will be sold to the highest bidder. That means gas fracked in Lancashire won't necessarily end up boiling England's kettles.

It's also unclear what impact European shale gas may have on energy prices. While greater gas supply could help bring prices down, the small quantities mean it's unlikely to have the same impact on the market as the US's shale gas boom.

Moreover, a dash for gas could be bad news for Europe's climate change commitments. Research by the UK government's official scientific advisor, the Committee on Climate Change, suggests the country may have to abandon its legally binding climate change targets if it wants more gas in the system. Likewise, European gas use would have to be scaled back if the EU is to keep to its collective commitment to reduce emissions by 20 per cent by 2020.

But domestic production isn't the only alternative. Europe is also hoping to get its hands on some of the US's shale gas in the form of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

LNG accounted for about 18 per cent of Europe's gas imports in 2012. As many ports are currently being underused, there's demand for more.

Source: Data from Eurogas, graph by Carbon Brief

Unfortunately for Europe, it has to compete with other continents for the fuel - in particular, Asia. For instance, Japan is currently using LNG to fill much of a capacity gap created by its decision to suspend nuclear power generation. So even if Europe can import more LNG - helping security of supply - it would have to be willing to match Japan's price.

And LNG comes with the same climate caveat as shale gas: if the EU is going to keep to its climate commitments, it can only be a temporary fix. As such, Europe may be wiser to invest elsewhere.

Relying on non-Russian sources of gas isn't the only fossil fuel option, however. Europe could instead burn more coal.

That may be the cheapest option. After all, cheap US coal has been flooding the European market for years, driving up demand and depressing prices. But that would be worse for the EU's emissions targets than pursuing gas. It can also have a significant negative impact on citizens' health.

And around a quarter of the EU's coal imports come from one country - Russia. So other than keeping energy cheap, it's not clear what importing more coal would solve.

Renewables

An alternative is for policymakers to accelerate the deployment of renewable energy technologies. Doing so could boost countries' domestic power supplies at the same time as helping them to reduce emissions.

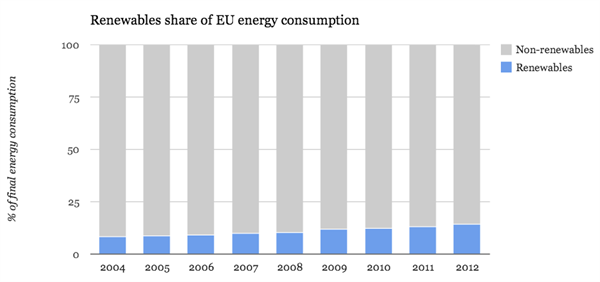

In fact, part of the reason policymakers are more sanguine about Russia's recent moves than they were during a similar episode in 2009 is because of the region's greatly increased renewables capacity. Renewables currently account for about 14 per cent of the EU's energy consumption:

Source: Data from Eurostats, graph by Carbon Brief

But renewable energy supply is variable as it depends on whether it's windy and sunny, so it still needs some fossil fuel back-up. A European "supergrid"connecting country's electricity systems could help overcome this - carrying power to parts of the region in need when generation is plentiful elsewhere. But a system like that would take years to build, and policymakers continue todebate the cost-effectiveness of ramping up renewables.

So wind, solar, and hydropower can't be solely responsible for Europe's energy security just yet.

Energy efficiency

Increasing domestic supply isn't the only way to combat a potential Russian squeeze, however. Implementing policies to reduce demand could be just as effective. The argument is simple: if Europe uses its resources more efficiently, it won't need as much fuel.

Unfortunately, many of the countries most reliant on gas imports are also the least energy efficient. So if policymakers decide efficiency should be a prominent part of Europe's energy security strategy, there could be plenty of work to do. Consumers also often don't get a financial return on their investments for many years - often decades - making them a less attractive short term proposition.

Having it all

So there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Most options could increase Europe's security of supply to a greater or lesser extent. Some options could bring energy prices down in the short or long term, though for many it remains unclear.

When it comes to Europe's climate security there are a couple of clear winners, however - ramping up renewables and implementing energy efficiency policies. But whether or not that remains a priority depends on policymakers commitment to their domestic and regional climate goals.

So when a politician next appears on television saying Europe must do something for security reasons, it may be worth asking what it is they're trying to secure.

This post by Mat Hope originally appeared on The Carbon Brief