UK hydrogen and the route to market [Gas in Transition]

The UK has many of the necessary attributes for a hydrogen market in terms of infrastructure.

But as well as the thorny question of how to pay for the additional cost this transition will mean, there is also no obvious way to call it into being without new legislation.

There are also practical difficulties. So far all the hydrogen that is transported in the UK is “grey” – reformed from methane for industrial purposes with no carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) in mind – and produced and consumed within a closed network.

If networks are to be interlinked on the scale implied by CCS, a new quality specification will have to be agreed.

Superficially the same as blue hydrogen, green hydrogen can be above 99.9% purity, a few percentage points above blue hydrogen. But green hydrogen is not expected to become cost-competitive with blue hydrogen for 20 years or more.

And there is no network yet available. Transmission system operator National Grid therefore is still considering the expensive option of injecting hydrogen into the grid, where it mingles with methane, and filtering it out as pure hydrogen as needed at exit points.

Other countries in the EU may therefore be some way nearer a hydrogen economy than the UK, according to Angus Paxton, principal at AFRY Management Consulting and member of National Grid’s Future of Gas Forum Steering Group.

The Dutch, for example, already have pipelines carrying low and high calorie gas and nitrogen. With Groningen gas on the way out, they will have some redundancy in their pipeline network that may be adapted for hydrogen, he says.

Other EU states might also be able to tackle the matter more easily than the UK: for example in Germany, municipalities take responsibility for domestic energy supply. But with the nationalisation of the UK gas industry in 1948 and the introduction since then of competition down to the individual household, there is no direct way for government to impose its will at a local level without new legislation, he said. “There is currently no coherent master plan for hydrogen or an agreed way to regulate the transition of the British gas pipeline network.”

The other major route to decarbonising is the electrification of domestic heat and that does not require legislation – just inducements to households to make the switch.

This suggests an alternative approach, Paxton says: the grid is going to have to be reinforced anyway to allow for the charging of electric vehicles. But that too has drawbacks, as the failure to introduce smart meters has shown: every home was supposed to have such a meter by last year but the attractions were never sufficient to overcome the natural resistance of many householders. Most consumers will go for a like-for-like replacement when their boiler breaks down, he says, and a boiler can last 20 years.

But it is different for major consumers: some industries will have to switch to hydrogen if they are to survive: steel, recycling and cement for example, Paxton says. This however will need some modification of processes and perhaps the burners.

Modelling on the past

There are plenty of supportive factors for the UK. It had Europe’s first liberalised gas market with third party pipeline access and customers of any size free to choose their own supplier. It has a long regulatory history of competition management, with price controls for the network operators. The latest methodology rewards network operators for innovation, and many network owners do not need any second bidding to spend to grow their regulated asset base (RAB). But that might not be the best way forward, Paxton says.

“The gas distribution network operators are happy to build pipelines and work with hydrogen because that is their only future, but who is to say that hydrogen pipes should be part of their RAB?” Paxton asks. “What about opening it up to competition, so a disused or spare gas pipeline becomes a part of another entity's RAB if they tender at a lower price? It is the public that has always paid for the regulated pipelines – regardless of use.”

“The gas distribution network operators are happy to build pipelines and work with hydrogen because that is their only future, but who is to say that hydrogen pipes should be part of their RAB?” Paxton asks. “What about opening it up to competition, so a disused or spare gas pipeline becomes a part of another entity's RAB if they tender at a lower price? It is the public that has always paid for the regulated pipelines – regardless of use.”

The UK has extensive on- and offshore infrastructure that can be repurposed to carry hydrogen and CO2 instead of methane. The UK’s National Balancing Point is the second most liquid trading hub in Europe and it is also home to three regasification terminals and two import/export pipelines.

National Grid posits a future hydrogen economy that tracks the same core principles of today's natural gas market: competitive, liquid and liberalised.

The challenge will be the transition to this end state, although for National Grid this will be an academic matter.

The operator is selling off a majority stake in the high-pressure network to focus on electricity. It has already sold off its low-pressure networks, with their 11mn connected households and commercial premises, which are now trading as Cadent.

Nevertheless it has published scenarios that show alternative pathways for hydrogen market development that consider the indicative tipping points into potential new styles of market arrangements.

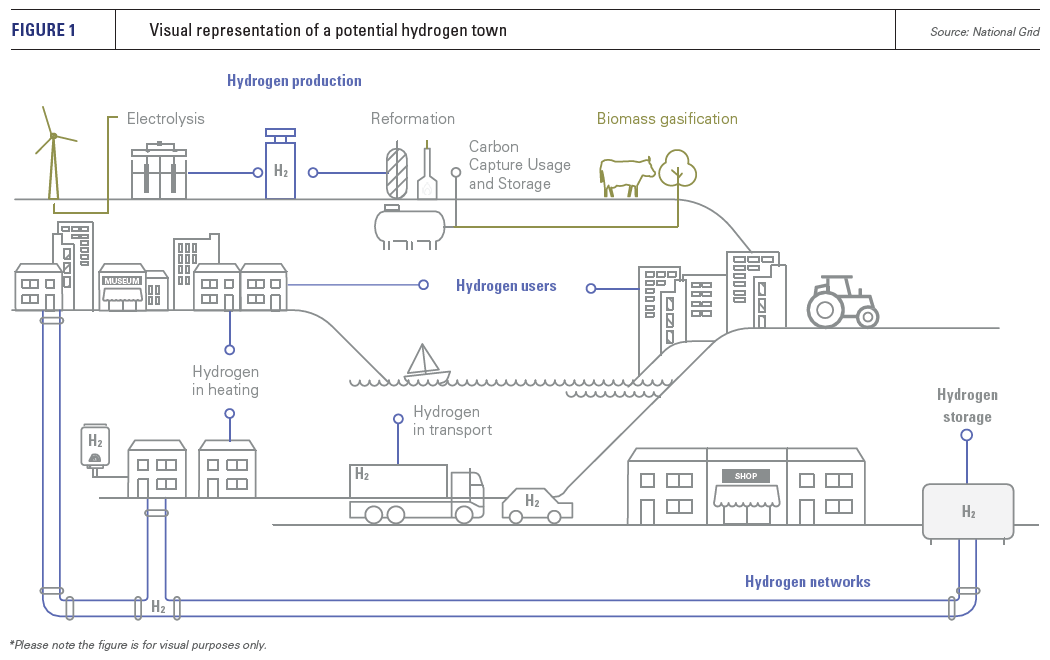

National Grid has produced a paper considering how a hydrogen market might emerge, starting with a “hydrogen town”. This will play an experimental part in the evolution of the market and the accompanying regulatory frameworks for a wider hydrogen transition within Great Britain.

Despite the challenges of hydrogen, entrepreneurs and private capital have been quick to embrace it. For example, network operator SGN and MacQuarie bank are considering a hydrogen hub to supply large energy users and heavy transport in one of the biggest ports: Southampton.

But not all towns are alike and some possess advantages where hydrogen is concerned: what works well for an industrial complex near a beach terminal would not work for an inland city like Oxford, or a place like Southampton, for which different solutions would be needed, Paxton says.

The form they take will vary from locality to locality and some have taken the green initiative – East Anglia springs to mind – with more enthusiasm than others. And despite Bacton being located in East Anglia, local industry has focused on green hydrogen, capitalising on the large wind farms offshore.

“Will regions trust central government to make decisions that affect them differently?” And conversely, Paxton asks, will central government trust regions to make decisions that deliver national targets?

Mapping across from gas

The gas network code achieved the seemingly impossible objective of defining the thousands of miles of pipeline and all the associated infrastructure and reducing them to entry/exit points for which shippers could compete for capacity.

This provides a template for a hydrogen market, with rules on balancing, charging methodologies and connection processes all established and regulated as needed.

Ofgem's powers to regulate the existing gas network and markets derive from the Gas Act 1986 and this includes hydrogen, it says, although this has not been tested so far.

But there cannot be a simple read-across from methane to hydrogen at a national scale. A hydrogen town network would be much smaller than the existing natural gas network, which raises questions about shortening the balancing regime which is daily for gas; as well as the requirements for storage for daily, inter-day and inter-seasonal balancing needs.

Hydrogen trading arrangements will be needed to allow the discovery of efficient commodity prices.

Other hydrogen market questions that need further exploration include the minimum number of players to initiate a traded market and at what size does a liquid traded market become valuable. This leads on to the question of liquidity in a regional market and whether different kinds of hydrogen would need to be included in order to generate sufficient supply and demand.

Hydrogen product pricing will depend on the outcomes of hydrogen business models, and the government aims to finalise hydrogen business models in the coming months

Regulation of the CO2 pipelines also remains undetermined. Energy regulator Ofgem said in its Forward Work Programme in March 2021 that it expects to be providing advice and developing regulatory mechanisms to enable investment in CCUS and new nuclear power, where requested by government.

The government said in May that the regulator’s role would be similar to what it is for electricity, gas, water, telecoms and transport. Regulation there has supported substantial private-sector investment over many years it says, although a light touch might be needed to stimulate investment and prime the pumps.

Ofgem is already supporting trials for blends of up to 20% hydrogen along with 100% hydrogen pipelines. These include the H100Fife, HyDeploy, H21 and HyNTS/Future Grid projects in various parts of the British mainland.

CCS

Hydrogen plus CCS is a great opportunity for UK plc, Paxton says, criticising the backtracking by government a decade ago when it cancelled a competition for CCS linked to power generation. “That was a mistake, he said: “A lot of time has been wasted.”

Five of the country’s six gas terminals are possibly blue hydrogen plus CCS hubs; of those, four are conveniently near industrial centres: Barrow on the northwest coast, Theddlethorpe and Teesside on the east coast and St Fergus in northwest Scotland. All have upstream sponsors with legacy infrastructure. Bacton by contrast has no nearby CO2-emitting industries although it is very near the densely populated southeast; and it has pipeline connections to the continent.

Blue hydrogen produced at Bacton, according to a study published early June written by Progressive Energy on behalf of the OGA, could help to decarbonise London and southeast England. Later on, it says, green hydrogen could be produced by the planned 15 GW of wind capacity in the area which, “if totally committed to green hydrogen production, could meet around half of the total estimated demand in the area by 2050.”

Bacton, which is receiving a major push towards CCS from the upstream regulator Oil & Gas Authority, has had the least buy-in. This is perhaps because companies have limited resources to spend on projects such as this and are focusing on the more obvious projects. Shell, a major infrastructure operator there, says Bacton is not a priority for government as there is no industrial CO2. It is one to watch, however.

At Barrow, Italian Eni’s plan for CCUS is based on its Liverpool Bay fields.

It has a storage appraisal licence for Hamilton, Hamilton North and Lennox gas fields of which it has “extensive geological knowledge, having owned and operated these fields for many years.” The fields to be re-purposed for storage are nearing the end of their productive life and the future process will be one of CO2 injection into these fields rather than gas production, Eni told NGW.

It is thus able to model accurately the behaviour of the fields, following two years’ technical efforts to study the suitability of the fields for re-use for carbon storage in particular. “These studies will continue as part of our responsibilities as CO2 storage licence holder, in order to make a formal submission to the OGA for a storage permit in the months to come. The basis of design for the Liverpool Bay CO2 storage considers an injection rate of 10mn mt/yr at peak. The fields have a total storage capacity of around 200mn mt,” it said.

The HyNet North West project grouping emitters in the northwest secured a funding commitment of £72mn in March, which will be released over the next two years to support detailed engineering studies. Eni will have to provide match funding under “state aid” rules.

At St Fergus, Anglo-Dutch major Shell is among the investors in the “building block” Acorn CCS project, with equal partners Harbour Energy and Storegga.

Shell owns the Goldeneye field and associated pipelines that will be repurposed to transport and house the CO2, assuming an investment decision is made. St Fergus is also the delivery point for over 30% of UK gas production, making blue hydrogen a part of the plan.

Shell has been involved in the feasibility study where the partners hope to quantify the demand for CCS from industrial users and power generators, including in continental Europe, who might deliver liquefied CO2.

Like a gas field operating in reverse, the expectation is that CO2 injections will start off small, once the investment has been underpinned by input commitments, and then rise as demand for the service grows from more industrial scale emitters.

And at Theddlethorpe, Neptune Energy has engaged with CO2 emitters and hydrogen offtakers in the South Humber industrial area as well as with industrial gas manufacturers and is confident there is demand for both the transport and storage service and the manufacture and supply of blue hydrogen. The next stage is to develop an end-to-end value chain consortium combining CO2 capture, transport and storage together with blue hydrogen production and offtake.