Total’s Algerian deal [NGW Magazine]

The proposed sale of Anadarko Petroleum’s African assets to France’s Total has brought to the fore a number of historical grievances in Algeria. The north African state is desperately in need of foreign investment in order to sustain gas production, in the face of rising domestic demand, but the choice of Total is a difficult one for Algiers.

Reuters reported, on May 26, that the Algerian minister of energy and mining Mohamed Arkab was set to block the sale of Anadarko’s assets to Total.

Citing the lack of a direct agreement between Total and Anadarko, the minister said Algeria had received no explanation of the plan. “We have good relations with Anadarko and we will do the utmost to preserve Algeria’s interests, including using our pre-emption right to block the sale,” he was quoted as saying.

Subsequently, tones have softened. Asked for clarification on his comments, Arkab said Sonatrach would seek a good compromise on the deal, noting that Algeria needed to work with foreign partners to execute its programmes.

Total’s CEO, Patrick Pouyanne, took an upbeat stance on the deal, saying that the company would hold discussions with the Algerian authorities. He went on to describe Total as a partner of Algeria. Two years ago Total put two lost disputes over tax behind it and resolved to co-operate more closely with Sonatrach in upstream, petrochemicals and other projects.

While high-level talks are sounding positive, the deal remains under intense scrutiny from Algeria’s newly energised populace. Demonstrations, which continue every Friday, have seen a number of placards complaining of the Total deal. Resource nationalism has never been far from the surface in Algeria. This, combined with antipathy towards former colonist France, may yet throw off the deal.

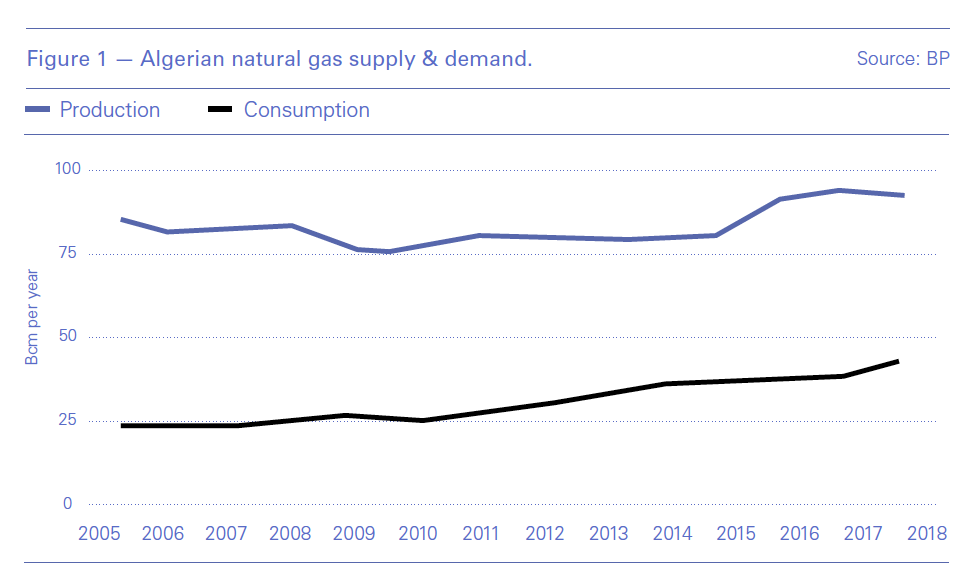

Algeria needs foreign investment, though, as the gap between production has continued to fall. In 2008, Algeria had 58.2bn m³ – when domestic demand was taken from production. This had fallen below 50bn m³ in 2018, by which point demand was up from 24.4bn m³ to 42.7bn m³.

Dealings

Part of the problem with Total’s acquisition of Anadarko’s assets – via Occidental Petroleum – is the speed with which the deal was done. Oxy was in the midst of a competition for Anadarko and felt the need to increase the amount of cash it was offering.

Chevron launched the first bid for Anadarko on April 12, offering $33bn, or $65/share, of which $16.25bn was in cash.

Oxy made a competing bid, on April 24, offering $76/share, including $38/share in cash. The company issued a revised bid on May 5, increasing the cash component of the offer to $59/share.

Increasing the cash stake was made possible by two deals agreed by Oxy. One was the $8.8bn sale to Total, covering Anadarko’s African assets, on May 5. The other was a $10bn cash injection – through the issue of preferred stock paying a hefty 8% dividend – from Berkshire Hathaway on April 30. Activist Carl Icahn has calculated that Berkshire Hathaway’s preferred stake will come at a cost of $800mn/year for Oxy.

Chevron announced it would cease its pursuit of Anadarko on May 9, commenting that it did not intend to win the bidding war “at any cost”. Taking some of the sting out of the disappointment for the major is the break fee, with Anadarko on the hook for $1bn.

Oxy executives had to tie up support for their plan quickly and Total had to commit rapidly in order to provide it with the required financial firepower. The importance of securing approval from host governments appears to have been overlooked, although the political changes that have rocked Algeria in the first half of the year are likely to have complicated matters.

Assets

Announcing the Oxy deal, Total said it was acquiring a 24.5% stake – and operatorship – in Blocks 404a and 208, which covers the Hassi Berkine, Ourhoud and El Merk fields, in the Berkine Basin. Total already owns a 12.25% stake in these assets via its purchase of Maersk Oil, which closed in August 2018. These fields produced 320,000 barrels of oil equivalent (boe) gross in 2018.

Total has been in Algeria for some considerable time – since 1952, pre-dating commercial oil discoveries – but production has been fairly muted, at only 15,000 boe/d in 2017. Following the Maersk deal, and indications from Algeria that it recognised the need for foreign investment, Total is expanding its position in the country.

The Timimoun gas field, in southwest Algeria, began producing in March 2018. Total has a 37.75% stake in the development, which will ramp up to 1.8bn mׇ/year. Timimoun had been intended to start in 2016. In October 2018, the company signed up to develop the Erg Issouane gas field, on the TFT Sud permit, and plans for a petrochemical joint venture with Sonatrach, in Arzew.

The El Merk interests – gained through the Maersk and Anadarko deals – provide access to the lowest wellhead cost gas, according to an OIES study by Ali Aissaoui. El Merk gas cost $0.3/mn Btu, he found, based on a survey, while Timimoun was the most expensive, at $4.7/mn Btu, because of the tightness of the reservoir.

Inside Algiers

Against this background of global wheeler-dealing, Algerian politics play a crucial role. The fall of the Abdelaziz Bouteflika regime in early April has thrown the country into a state of uncertainty. The president’s resignation was triggered by mounting public protests and was, ultimately, endorsed by the Algerian army, under the military chief of staff, Ahmed Gaid Salah.

An interim government took over operations and committed to holding a presidential election, with the date set for July 4. However, on June 2, the constitutional court cancelled the election plan. While the thinking behind this decision was not made clear the protests have continued, with demonstrators demanding much wider ranging reforms than had been proposed.

Given the interim nature of the government, its officers lack legitimacy. The armed forces, the Armée Nationale Populaire (ANP), is the most effective source of power but, given its close links with the populace – made up as it is of conscripts – is responsive to the demands of the people.

Arkab took up his post leading the energy ministry at the end of March, as part of the broader reshuffle. The minister had previously served as the head of Sonelgaz, Algeria’s state-owned power and gas distributor.

Under the previous administration there had been a clear policy of improving terms for foreign investors in a bid to bolster production. “Talks with Sonatrach officials, in December, focused on the centrality of working with foreign oil companies. These foreign companies were also very optimistic about the changes coming to Algeria, with Sonatrach seen as a supportive partner – the companies liked the new terms,” Chatham House’s Valerie Marcel told NGW. But she said that while Sonatrach had settled all its arbitration cases with foreign companies by the end of 2018, “this new dispute with Total signals a potential return to a tougher line with oil companies."

Collaboration with foreign companies was a particular focus, amid Sonatrach’s broader reform drive, known as Horizon 2030. It is this question of working with foreign companies that may be difficult, amid the political changes there could well be a price to pay for seeming to grant too easy a ride to investors such as Total.

Marcel went on to say Sonatrach’s restructuring plans – and whether these would continue – would be a key point to watch. “This programme shouldn’t upset anyone, it’s good for the industry, it’s good for the companies, it’s good for Algeria.”

Companies already working in Algeria should face an easier time. Business as usual will continue and companies can secure “derogations”, providing exemptions from some of the rules under the 2005 law, Marcel said.

There are no guarantees about the broader changes to the laws, though. “If production and reserves decline, this may spur a discussion around how to tackle this problem, which could pave the way for reforms and a better environment for foreign companies. Otherwise the political process will run its course, but this will be long.”

Sonatrach, in May, said exports had reached 51.5bn m³ of gas in 2018. Exports, of both gas and LNG, went primarily to Europe and Turkey.

There is clearly room for expansion in Algeria’s production. In addition to its conventional resources, it has substantial – and largely unexplored – shale plays. As demonstration of the country’s continuing prospectivity, Sonatrach announced a discovery on May 22, bringing the number of discoveries in 2019 to eight.

Algeria has managed to keep production relatively stable over the last 10 years, but domestic demand is rising – up 9.9% last year, according to BP’s latest statistics.

The new government lacks legitimacy but will be aware of its need to bolster production – in order to meet domestic needs and sustain exports, in order to keep the cash rolling in. That said, a deal allowing Total to take a major stake in the country’s producing assets would face resistance and runs the risk of reversal under the next government. Current politicians considering their future, and the Total deal, may well opt to refuse such an agreement, or at the very least delay approval until it can be resolved by another.