To The Barricades! [NGW Magazine]

Following the lead set by the president, Emmanuel Macron, the new environment minister François de Rugy is changing the direction of French energy strategy by maintaining focus on nuclear.

He pleaded in September for an end to what he called the ‘religious war’ on nuclear power, indicating a more pragmatic approach to environmental strategy. This is an about-turn: his predecessor, Nicolas Hulot, favoured more renewables.

Following the surprising and dramatic resignation of Hulot, announced on live radio at the end of August, de Rugy was appointed environment minister September 4.

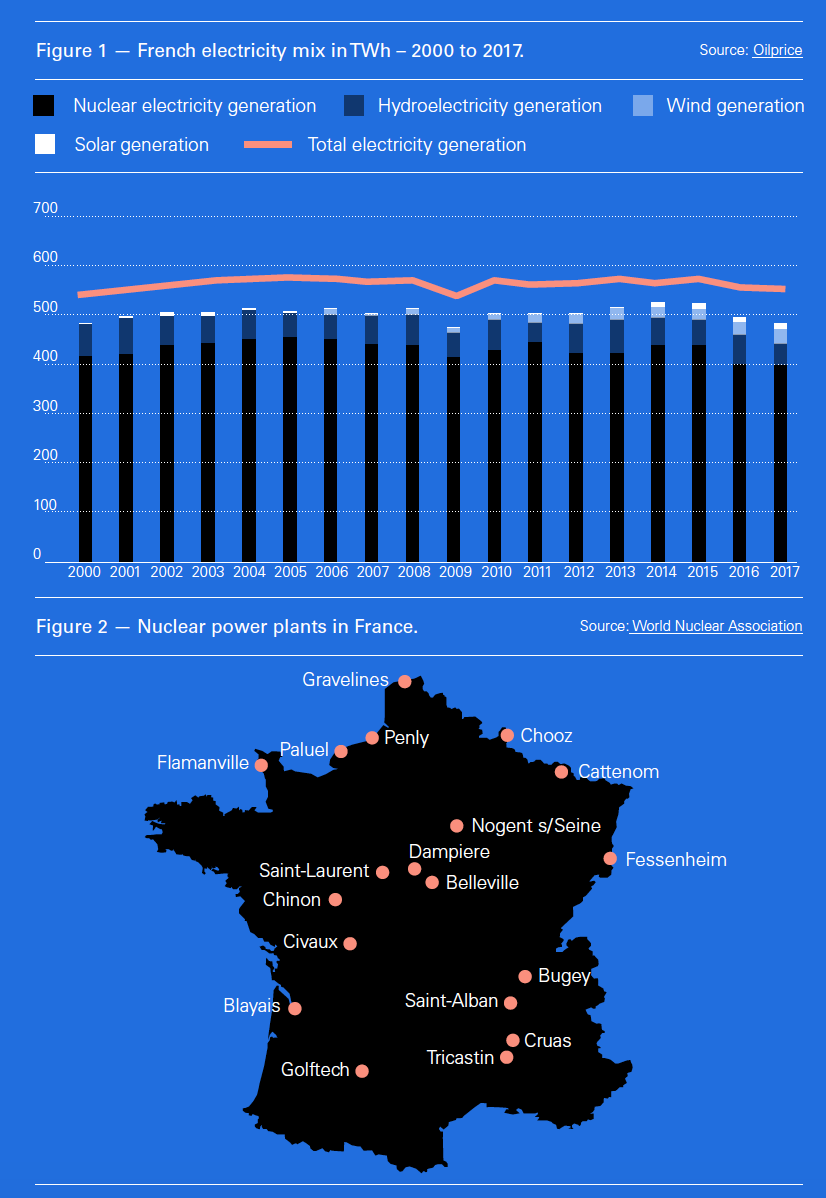

Nuclear provided about 72% of France’s electricity (Figure 1) in 2017, making the country’s energy one of the cheapest in Europe. But questions are being asked about dependence on ageing nuclear facilities. As a result, France made a legislative commitment in 2015 to reduce nuclear power to no more than half its current level by 2025.

Hulot used this to promote transition towards renewable energy sources and went as far as to say that this transition was irrevocable. However, he did reluctantly recognise that a speedy shift could risk power shortages. Just before he resigned he suggested slowing the transition until 2035.

Immediately after his appointment, de Rugy adopted a more pragmatic approach towards nuclear power, stating: “The important thing is to know the economic data in the nuclear field and in the field of renewable energies.” While not giving details of changes to the energy mix, he said that a revision of France’s multi-year energy programme (PPE) will be released by the end of October. In fact this revision was released November 27.

The current PPE covers the period 2016 to 2018 and the revision will cover the two periods 2018-2023 and 2024-2028.

He added that the government aims to rebalance the energy mix in line with the energy transition commitment made in 2015, including details of the “types of energy and the transformation we want with development of renewable energy sources.”

Energy transition

In 2015 the government adopted a Green Energy Transition law. The main provision was that by 2025 the share of nuclear energy would halve.

Other objectives mirror official objectives of European Union energy policy, through such measures as:

- Promoting green growth and environmentally friendly economic development, efficiency and innovation;

- Offering consumers competitive energy prices;

- More secure energy and lower import dependency;

- Guaranteeing nuclear safety;

- Fighting energy poverty.

In order to support these objectives, the law included:

- Diversification of sources of energy supply and less fossil fuel use;

- Promoting energy efficiency by limiting demand;

- Guaranteeing the poorest people access to energy and energy services;

- Ensuring transparent energy costs and prices by including health and other external considerations.

Specific targets included:

- Limiting nuclear power to 50% of the output by 2025;

- Cutting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by two-fifths between 1990 and 2030 and by three-quarters by 2050;

- Cutting final energy demand by a fifth between 2012 and 2030 and by half by 2050;

- Cutting primary fossil fuel demand by 30% between 2012 and 2030;

- Making renewable energy supply 23% of gross final energy demand by 2020 and 32% by 2030. Renewable energy must represent 40% of electricity production, 38% of final heat demand, 15% of final fuel demand and a tenth of gas consumed by 2030.

- Lower air pollutant emissions as defined in the Environmental Code;

- All buildings to meet ‘low energy consumption’ standards or similar by 2050.

In order to ensure these objectives, a commitment was made to present a report to parliament in the six months preceding the end of the PPE. The report and the ensuing evaluation of public policies could then lead to a revision of the long-term objectives of this law.

When elected, the president, Emmanuel Macron, accepted this law and adopted the shift to renewables. However, he also said that reductions in nuclear power must be at a pace which allows France to retain energy sovereignty and security. This is what led to the need to review the country’s energy strategy. But all other provisions of the 2015 Green Energy Transition law still stand.

Revised energy strategy

As part of the PPE review process, Macron unveiled France’s revised energy strategy on 27 November. The key provisions were:

- Closing two reactors at the Fessenheim nuclear power plant by 2020;

- Closing 4-6 nuclear reactors by 2030, of which 2 are to close by 2027 to 2028

- and possibly 2 by 2025 to 2026

- Closing 14 reactors out of 58 by 2035.

He also said that a decision on building nuclear reactors would not be taken before mid-2021.

Macron made clear that this closure plan is contingent on not jeopardising France’s security of power supply. The closure schedule depends on how the country’s energy mix, including renewables, develops. He went on to say: “It is a pragmatic approach... that takes into account security of supply.”

In presenting the plan, he said: "Nuclear energy allows us to benefit from low-carbon, low-cost energy. I was not elected on a promise to exit nuclear power but to reduce the share of nuclear in our energy mix to 50%." This means that by 2035 the share of nuclear energy in the country’s power mix will reduce from about 72% in 2017 (Figure 1) to 50%.

A factor that led to this revision was a warning issued by France’s grid operator RTE that the country risked electricity supply shortages after 2020 and could miss its goal to curb carbon emissions. Another factor is that nuclear power is cheap: French electricity prices are the lowest in Europe.

Acting on CO2 emissions is becoming urgent. After declining rapidly in the period 2005 to 2014, they have since been rising at an average rate of 2%/yr.

As part of the revised energy strategy, Macron made a commitment that France will become carbon-neutral by 2050. In order to achieve this, it will close all coal plants by 2022 and will accelerate development of renewable energy, but will not give up nuclear.

He emphasised that the priority is closing coal power plants and that is one of the reasons he took the decision to slow down phasing out nuclear. He said: “I don’t want us to be in a situation where closing down nuclear power stations leads to coal-fired power stations being closed down more slowly.”

Impact on nuclear industry

EDF owns and operates all of France’s 58 nuclear power reactors at 19 nuclear power plants (Figure 2), with a total installed capacity of 63 GW and with an average age of 33 years. These were built over a 20-year period, starting 1978. As a result, the oldest plants are now nearing the end of their lives. This is what led Macron’s predecessor Hollande to commit in 2015 to reduce nuclear power to 50% by 2025. The revised strategy extends this by ten years to 2035.

Despite the strategy shift, the French nuclear industry is still under pressure. De Rugy has already said that EDF must prove the viability of its next generation nuclear reactor before the question of new plants can be considered: “EDF should demonstrate that the European pressurised reactor (EPR) works, which is not the case yet. Nobody is able to guarantee a date for its connection to the grid. It also has to demonstrate that the EPR is competitive in terms of costs.”

These comments were prompted by the problems Flamanville (Figure 2), the EPR prototype, is facing. It is seven years late and €7bn over budget.

This is the reason why the government will now leave the decision on whether or not to build a new generation of EPR reactors to between 2021 and 2025. Guaranteeing that the industry would be able to produce energy at a reasonable price will be a key factor.

The government also said that it is not possible to determine with certainty what will be the most competitive form of electricity generation with which to replace existing nuclear reactors beyond 2035. As a result, it will maintain the option to build new reactors in future.

Confirming the importance of nuclear power to France’s energy future, Macron said “Nuclear power now allows us to benefit from low carbon and low cost energy. This is a reality, and this is why we will start work on a new regulation of the existing nuclear fleet.” He has also requested EDF to work on the development of a new nuclear programme, in time to meet the 2021 decision target date.

Impact on renewables

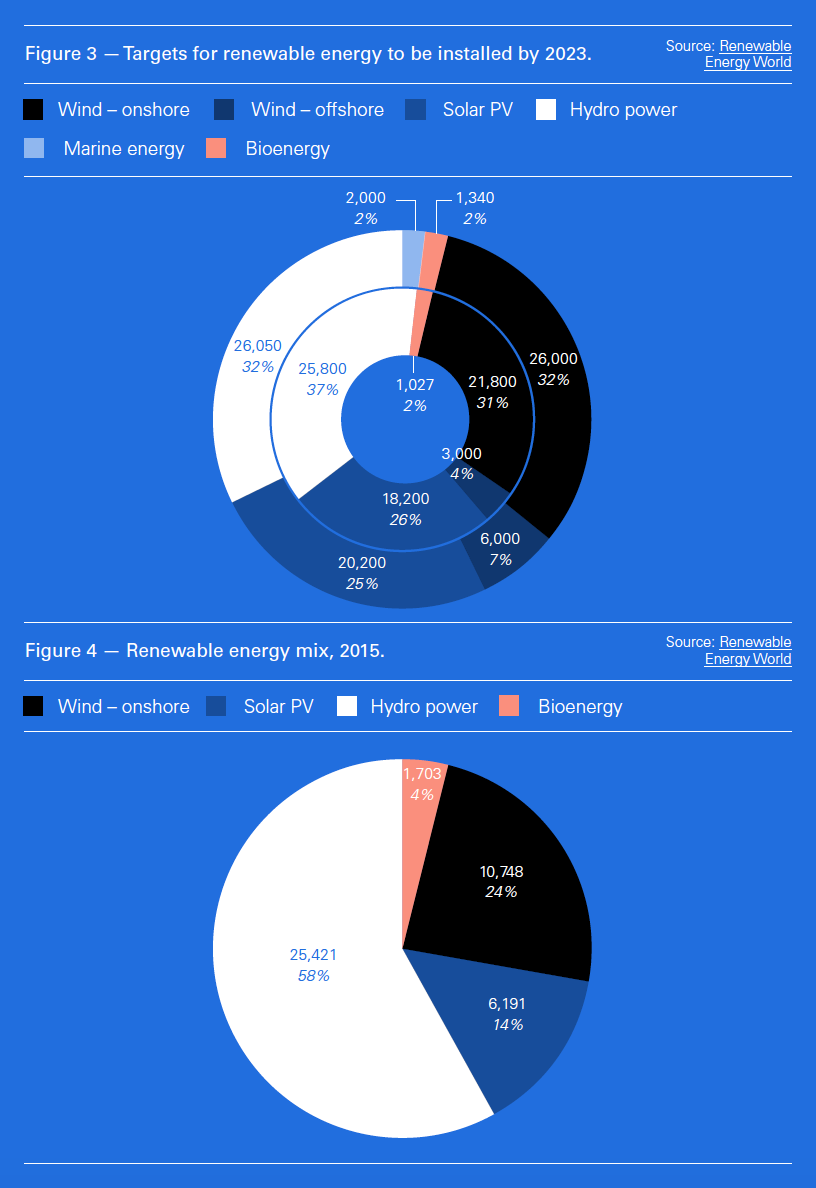

The existing PPE provides targets for renewables to be installed by 2023 (Figure 3), based on a low (inner circle) and a high scenario (outer circle).

The impact of these new targets can be better understood when compared to France’s renewable energy mix in 2015 (Figure 4), the year when France’s Green Energy Transition law was adopted.

The renewable capacity targets to 2023 in the PPE are: low ~ 70 GW, high ~ 77 GW. These constitute a substantial increase on the 2015 capacity of 44 GW, with most coming from wind and solar.

However, not unexpectedly, the renewables industry views the new commitment to nuclear power with dismay. Even before the new strategy was unveiled, Xavier Daval, Chair of SER-SOLER, the solar commission of French renewable energy association SER, went as far as to say “We could define this plan as an Energy Frexit…. With more than 70% of nuclear energy as base load of the French electric mix, the bigger the volume of renewables, consisting of wind and solar being not dispatchable, the higher their disconnection will be.”

Daval added that without reducing nuclear power to 50% by 2025, it will be difficult for the solar industry to make commitments to achieve the solar power targets, set previously by former environment minister Segolene Royal, to achieve 20 GW by 2023. So far only 8.5 GW have been installed.

The floating wind industry has also been pressing the government to include up to 5 GW floating wind capacity in the country’s revised PPE, to be brought online by 2030. The industry warned that tenders must be issued by next year if the current dynamics of the French market are not to be interrupted. Any delays would cause a slowdown or even a halt in investment programmes. France received its first offshore wind power in September.

The new energy strategy committed to increase funding for the development of renewables from €5bn/yr now to about €7bn/yr, with a total of €71bn to be spent between 2019 to 2028. Macron said this public support should enable France to triple wind power, from 15 GW now, and increase solar power by a factor of five, from 8.5 GW now, and in the process boost the share of renewables to the power energy mix to 40% by 2030, from about 18% now. Of that, less than 7% is wind and solar.

There is also a commitment to develop offshore wind, geothermal power and biogas. He also said that a more ambitious scenario, with a faster transition, can be adopted depending on renewable energy storage innovation.

In order to keep costs down, France is committing to develop more power interconnectors with neighbouring countries so that it can ensure security of supplies and benefit from the least-cost power. In fact, France is the world's largest net exporter of electricity, thanks to its very low cost of generation: it gains over €3 bn/yr from this.

In addition to increasing wind and solar power, the government plans to strengthen rules governing citizens or business ‘prosumers’ and their connection to the traditional energy market. Apparently three in every four French households want to become prosumers.

Impact on natural gas

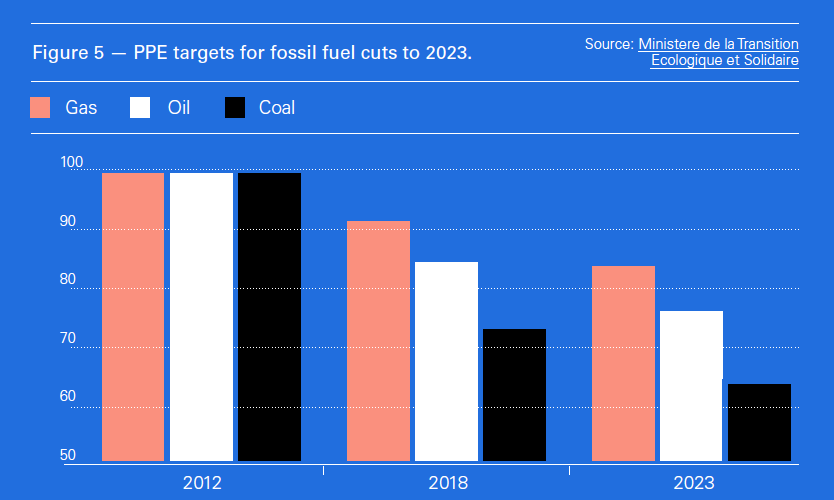

The existing PPE envisages reduction in primary fossil fuel consumption by 22.6% by 2023 and by 30% by 2030, compared with 2012. The corresponding targeted reductions for oil, gas and coal in the period to 2023 are shown in Figure 5.

For natural gas demand this means an average annual reduction of 1.5%. In fact, in accordance to BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy 2018, there has been no net change in the country’s natural gas consumption since 2012. Even though it went down to 38bn m³/yr in 2014, by 2017 it bounced back almost to its 2012 figure of 44.7bn m³/yr. This is about a sixth of France’s primary energy demand, making France the fourth largest gas consumer in Europe.

A commitment was made in July 2017 to end sales of diesel and unleaded cars by 2040, later extended to include a ban of any “new project to use petrol, gas or coal”, as well as shale oil, by that date. This was then followed by a law to ban all exploration and production of oil and natural gas on the country's mainland and overseas territories by 2040.

Even though symbolic, as France imports 99% of its oil and gas, it is indicative of the country’s commitment and transition to a low-carbon future. Going further, Macron has now committed to close all coal plants by 2022, accounting for close to 4% of primary energy demand, and to implement all France’s Paris Agreement pledges and make France carbon-neutral by 2050.

However, no new policies have been proposed so far with regards to the future of French consumption of gas, beyond Macron’s hostility to fossil fuels, a long-term target; and the phase-out of coal and closure of Fessenheim (Figure 2) could produce short to medium-term benefits for gas.

However, in the longer-term with the stronger shift to renewables in the new energy strategy and the delay in phasing-out nuclear power, gas might come under more pressure.

Social factors

The yellow-vest ‘gilets jaunes’, movement took to the streets in November to air its grievances against the higher fuel tax, driven in part by a carbon levy. In response, Macron initiated a three-month consultation on ecological and social transition in France in order to refine French ambitions with respect to the energy transition. He confirmed: “If we need to review the government’s ambition at the end of the consultation, I am willing to review it.”

Carbon tax in France is part of a long-term strategy to phase out fossil fuels, but it now has a disproportionate impact on those with modest income and the poor, hence the protests.

These have brought to the fore the dilemma of how to introduce policies that bring long-term benefits to the environment, in an affordable manner acceptable to the population. Recent public surveys in Europe and China showed that even though people are aware of climate change, they are not prepared to accept significant cuts to their lifestyle in order to combat it.

Even though Macron has agreed to review fuel tax levels every three months to reflect changing global crude prices, the ‘polluter pays’ principle is seen as a fair and efficient way to reduce carbon emissions; and he is expected to stick to it. During his speech on energy strategy, he said: “We should listen to the social alarm and protests, but there is also an environmental alarm,” insisting that he will not rethink his push for cleaner energy. He added “We must not give up the ecological transition, which is right and necessary... But it is a question of changing the method, because many fellow citizens thought that it was imposed on them from above.”

However, not everybody is happy with the new energy strategy, especially environmental groups. Alix Mazounie, head of Greenpeace France’s nuclear campaign, was highly critical when he said: “For the umpteenth time, the government has caved in to the nuclear industry lobby.” Environmentalists have also been asking for faster decommissioning of older plants to promote a faster switch to renewables.

There was also criticism that these measures do not help reduce greenhouse gas emissions rapidly and do not accelerate the transition toward renewable energy. The former minister Hulot was also critical, advocating more financial aid to help people cope with the costs of cutting pollution.

Macron noted the need for accurate information to be disseminated to the French public, and moved to install a “high council for climate action,” to enable transparency in France’s future-looking strategy, “which should allow to restore facts, scientific truth, elements on which, then, the debate must be fed, and opinions be confronted.” But he is fully committed to his newly announced energy strategy to make France carbon-neutral by 2050 and the need to retain nuclear power until renewables and electricity storage develop further.