The long march to Canadian LNG [LNG Condensed]

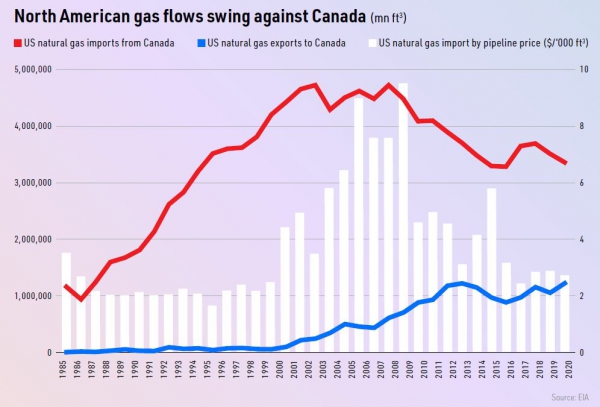

Even a few years ago, hopes were high that Canada could become a global LNG supplier on a par with Australia. The North American shale boom had priced a great deal of Canadian gas out of the US market, forcing investors to look to monetising their reserves through LNG. Shale gas could feasibly be piped to either the Pacific or the Atlantic coasts for liquefaction and shipping around the world. Some east coast plants were planned, but British Columbia attracted the lion’s share of planned development, mainly because the world’s biggest LNG markets lie on the opposite side of the Pacific Ocean and most Canadian gas reserves lie closer to the west coast than the east.

The Canadian federal government issued at least two dozen licences for export schemes, but the expected boom has not materialised. The pandemic has just been the latest in a long line of obstacles to development. There is considerable opposition to the construction of LNG plants and associated gas supply pipelines from environmental organisations, but particularly from First Nations, who have some say over whether projects are developed on their land.

The overall level of bureaucracy involved can also slow projects, as federal, provincial and municipal governments must all sanction development, along with First Nations where applicable.

Moreover, construction costs are relatively high in Canada, at least in comparison with the United States. The distances between gas fields and planned export terminals have also pushed up transmission costs on planned projects. As ever, uncertainty over international demand and prices has periodically deterred development.

Cancellations

Many proposed projects have already been cancelled or postponed. Indeed, according to Global Energy Monitor, a massive 240mn mt/yr of LNG production capacity has been cancelled or delayed in Canada, including 128.5mn mt/yr that has been officially cancelled.

In March, Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway group pulled out of the planned $6.7bn Energie Saguenay LNG project in Quebec. The company did not explain its decision and the fate of the scheme, which is to be built about 230 kilometres northeast of Quebec City, remains uncertain.

Most recently, Australian firm Woodside wrote down the value of its 50% stake in the Kitimat LNG project in February by $720mn. Partner Chevron has already said that it wants to sell its 50% stake.

In a statement, the US firm said: “Although Kitimat LNG is a globally competitive LNG project, the strength of Chevron Corp.’s global portfolio of investment opportunities is such that the Kitimat LNG Project will not be funded by Chevron and may be of higher value to another company.”

A Canadian think tank, the Conference Board of Canada, sought to rally support for the LNG industry with the publication of its Rising Tide report in July, which concluded that the development of 56mn mt/yr of LNG capacity in Canada by 2034 would boost GDP by $11bn/yr and create 96,550 new jobs.

However, the US Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) said that the report was based on the belief that “Chinese demand growth can sustain a further leap in British Columbian LNG capacity growth, despite corporate investors already folding their hands.”

Melissa Brown, the IEEFA’s director of Asian energy finance studies, commented: “The authors call on provincial and federal governments to risk sustained subsidies that may only yield stranded assets, depleted finances and delayed retraining obligations.” She said that “exaggerated demand assumptions and disregard for China’s manifest price sensitivity are the fatal misunderstandings of its argument.”

The Conference Board of Canada produced a similar report in 2016 that listed 18 planned LNG projects in British Columbia, yet only one of these has actually proceeded.

LNG Canada

The $18bn LNG Canada project in Kitimat, British Columbia, is the only project already under development. Kitimat lies at the head of the Douglas Channel, which is ice free all year, but is further inland than other prospective sites. The final investment decision (FID) was taken on the first phase in October 2018, which encompasses two trains with combined production capacity of 14mn mt/yr, while the second two-train phase would double capacity.

The biggest ever single infrastructure investment in Canada, the project is being developed by a consortium of Shell (40%), Petronas (25%), PetroChina (15%), Mitsubishi (15%) and Kogas (5%), with first gas now due to be shipped in 2025 as a result of Covid-related delays.

The company plans to take the FID on Phase 2 before Phase 1 is completed. LNG Canada’s director for corporate affairs, Susannah Pierce, commented: “Despite certain impacts resulting from the COVID-19 virus, LNG Canada and our engineering procurement and construction contractor JGC Fluor JV continue to hit critical construction milestones”, although contractor Fluor says that construction is behind schedule.

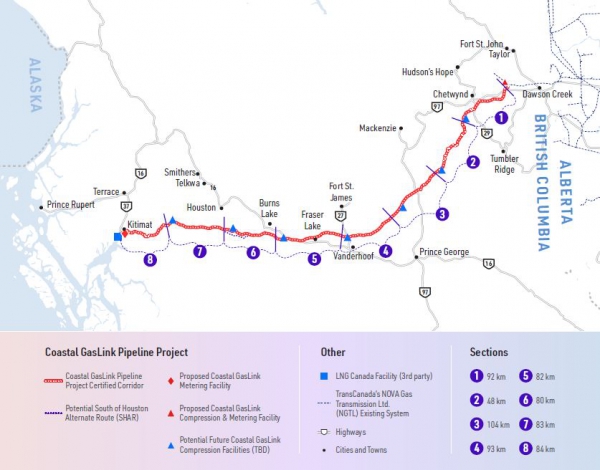

Despite the delays, construction of the offloading terminal, storage tanks and access roads has begun, while Baker Hughes is supplying the plant’s turbines and compressors. Work has also begun on the Coastal GasLink pipeline, which will supply the plant with the 1.7bn ft3/d from the Montney shale formation that will be needed in Phase 1, although this can be ramped up to 5bn ft3/d when required.

The project is owned by TC Energy, which puts capital investment on the pipeline at $6.6bn, with $42mn annual operating costs. By November, more than 500km of the 670km pipeline route had been cleared, but less than 50km of pipe had actually been laid.

One of the reasons why LNG Canada is the first project to be developed is the fact that the Coastal GasLink will lie entirely within British Columbia, simplifying the licensing and administrative process. Federal approval is only required for projects that cross provincial boundaries. However, opponents argue that even LNG Canada is only financially viable because of the subsidies and tax breaks available to LNG projects.

Alternative approaches

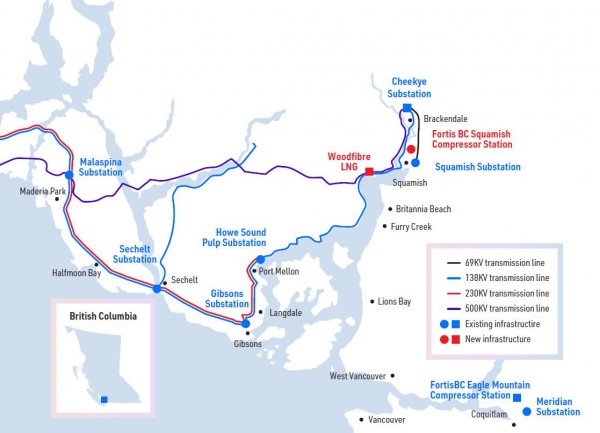

Work on another – much smaller project – Woodfibre LNG, has now been postponed until mid-2021 but is still due to proceed after BC's Environmental Assessment Office decided to extend its environmental assessment certificate, which was due to expire this October. Located in Squamish, north of Vancouver, it will have production capacity of 2.1mn mt/yr.

The project is being developed by Pacific Oil and Gas Ltd, which is owned by Indonesian investor Sukanto Tanoto. Woodfibre LNG has dropped plans to run its liquefaction turbines on gas in favour of hydroelectricity in order to cut its greenhouse gas emissions. The strategy of developers seeking to reduce project carbon emissions in order to overcome environmental opposition is becoming ever more common, particularly in order to influence the willingness of banks to finance LNG projects in Canada.

The involvement of First Nations and regional governments in LNG projects could erode opposition, particularly if a large proportion of revenues are used for the benefit of local people.

In mid-November, the Haisla Nation announced that it had concluded agreements with Pacific Traverse Energy and Delfin Midstream over the development of the Cedar floating LNG project in Kitimat with production capacity of 3-4mn mt/yr.

The Haisla Nation, which will take a majority stake in the project, aims to minimise the environmental impact of the venture, including by using air cooling technology and powering liquefaction with electricity. Gas for the project could be supplied by the Coastal GasLink pipeline, which will supply LNG Canada.

Northwest Territories

In October, the government of the Northwest Territories launched a request for proposals for companies interested in undertaking a feasibility study into developing gas reserves in the Mackenzie Delta, along with two floating LNG projects to be located 20km off Tuktoyaktuk with combined production capacity of about 4mn mt/yr. The water near Tuktoyaktuk is very shallow, presumably ruling out onshore development.

Previous plans to develop the region’s gas had focused on building pipelines to transport gas southwards, but North American piped gas prices are much lower today than when the Mackenzie Delta pipeline was first proposed, so the only viable markets seem to be overseas. At the same time, the impact of climate change on ice pack has opened up the option of shipping gas to Asian markets direct from the Northwest Territories.

The territorial government said: “Sea ice coverage and thickness is lower than it has ever been, and is anticipated to continue to shrink, reducing Arctic shipping concerns.”

Similarly, LNG produced in British Columbia will have substantially shorter sailing times to East Asia than from competitors on the Gulf of Mexico, while gas shipped from Nova Scotia on the other side of the country will be closer to Northwest Europe than any part of the US.

Covid-19 impact

East coast plants could make use of existing gas pipeline connections with the US, while it is even possible that gas could be sourced from further west in Canada given the higher gas prices on offer in Europe than in Asia. However, the Covid-19 crisis has exacerbated short-term oversupply in LNG markets, prompting developers to reconsider their plans.

For instance, Pieridae Energy was due to take the FID on its Goldboro LNG project in April, but has now delayed the decision. The 9.6mn mt/yr plant is due to be built in Nova Scotia with half of all gas from the project shipped to German company Uniper under a 20-year sale and purchase agreement with the support of a German government loan guarantee.

Announcing the delay to the FID, Pieridae CEO Alfred Sorensen said: “Over the last several weeks we have seen projects in Australia, Africa and the Gulf Coast either cancelled or delayed indefinitely due to the challenging energy market. We believe this is an opportunity for Canada to enter into this industry at a time when others are exiting.”

However, Uniper announced in November that it now is reconsidering its own plan to develop a 9.8mn mt/yr floating LNG import terminal at Wilhelmshaven in Germany, which would receive the Goldboro gas. In a statement, it blamed “economic uncertainty and market players’ reluctance to make binding bookings for import capacities at the planned terminal in the current circumstances.”

Uniper project manager Oliver Giese said: “Economic uncertainties have definitely played a role in the current circumstances. Many companies don’t want to make long-term commitments at the moment. The results of the expression-of-interest procedure show that we need to revise the scope and focus of the planned terminal to ensure that it remains attractive to market players and economically predictable.”

The company is considering switching its import plans from LNG to hydrogen. Pieridae has now employed Bechtel, which had been lined up to provide engineering, procurement, construction and commissioning services on the Nova Scotia plant, to review the scope and design of the project.

Outlook

While the development of the first LNG export project might have opened the floodgates for a string of other liquefaction projects in Canada, it is looking increasingly likely that the country will fail to make the most of its massive LNG potential.

Both of the main parties in British Columbia, the Liberals and the New Democratic Party, support the development of new LNG capacity, but opposition, financing difficulties and weaker-than-expected global demand mean that little more capacity may be added beyond LNG Canada, particularly in the face of competition from producers elsewhere in the world.

Much will depend on how fast demand grows in Asia in general and China in particular. Although the Chinese government has set a target of achieving net carbon neutrality by 2060, how Beijing perceives LNG’s role in this transition will be a major factor. It is currently relying on LNG to depress demand for coal and the air pollution associated with coal consumption.

However, LNG developers need to be confident that demand will remain strong for at least 20 years after their projects come on stream. Potential investors may therefore focus their attention on cheaper projects, if there is any doubt over demand.