The future is electric [NGW Magazine]

WEO 2018 has considered three different but possible scenarios, central of which is the New Policies (NP) scenario and with Current Policies and Sustainable Development respectively taking pessimistic and optimistic views.

The key message from the IEA is the same as that from the IPCC: averting catastrophic levels of climate change is possible, but only with urgent, ambitious, and sustained action from governments, investors, and businesses everywhere.

Overall, gas comes out best, forecast to become the second-largest source of energy after oil, overtaking coal by 2030. Demand rises by 45% between now and 2040. But that does not spell the demise of coal. The IEA expects coal demand to flatten out in real terms, thanks to continuing growth in demand in Asia cancelling out declines in Europe and the US. But renewables also come out well, and overtake coal in power generation. So everybody is a winner!

Based on the NP scenario, the key takeaways from WEO 2018 are:

- With population growing by 1.7bn by 2040, there will be a profound shift in energy demand to Asia, which will be felt across all fuels and technologies, as well as in energy investment.

- Asia will make up half of global growth in natural gas, 60% of the rise in wind and solar PV, more than 80% of the growth in oil, and more than 100% of the growth in coal and nuclear by 2040.

- The shale revolution will continue to shake up oil and gas supply, enabling the US to become the world’s largest oil and gas producer, accounting for nearly 75% for oil and 40% for gas production growth to 2025.

- Electricity demand will double as developing economies put cleaner, universally available and affordable electricity at the centre of their strategies for development and emissions reduction. Elsewhere demand growth will be modest, but the investment requirement is still huge as the generation mix changes and infrastructure is upgraded.

- But 700mn people predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa, are projected to remain without electricity even by 2040.

- The share of nuclear power will stay at around 10%, but China will overtake the US and the EU before 2030.

- A much stronger push for electric mobility, electric heating and electricity access could lead to a 60% rise in power demand from today to 2040. This will require additional measures to decarbonise power supply if it is to unlock its full potential to meet climate goals

- With 300mn electric cars expected on the road by 2040, oil use for cars will peak in the mid-2020s, but petrochemicals, trucks, planes and ships still keep overall oil demand on a rising trend. Petrochemicals will be the largest source of growth in oil use, which, even though it will slow down after the mid-2020s, will not peak and will reach 106.3mn barrels/day (b/d).

- The NP scenario puts energy-related CO2 emissions on a slow upward trend, increasing by over 10%, a trajectory far out of step with Paris targets to tackle climate change.

- This is addressed in the SD scenario which provides an integrated strategy to achieve energy access, air quality and climate goals in line with Paris targets. Renewable energy in the total power mix rises to about 65%, with energy efficiency keeping overall demand at today’s level.

- Natural gas and oil continue to meet a major share of global energy demand even in the SD scenario, accounting for around 15% of energy sector greenhouse gas emissions including CO2 and methane.

- China will remain the world’s largest energy user and the largest source of power sector emissions. But India will overtake the US as the world's second-largest power sector emitter, as millions of people rapidly ramp up their electricity use, with power use almost tripling and emissions rising by 80% by 2040.

The IEA stresses that government policies will shape the long-term future for energy, but policy-makers also need to ensure that all key elements of energy supply, including electricity networks, remain reliable and robust.

Increasing global energy demand

Under current and planned policies modelled in the NP scenario, energy demand is projected to grow by about a quarter. This is largely driven by Asia and would be twice as large in the absence of continued improvements in energy efficiency. Producing this additional energy cannot be met by renewables and nuclear on their own and will require more than $2 trillion/yr of investment in new energy supplies, including from fossil fuels.

The head of the IEA Fatih Birol said: “Our analysis shows that over 70% of global energy investments will be government-driven and as such the message is clear – the world’s energy destiny lies with government decisions.… Crafting the right policies and proper incentives will be critical to meeting our common goals of securing energy supplies, reducing carbon emissions, improving air quality in urban centres, and expanding basic access to energy in Africa and elsewhere.”

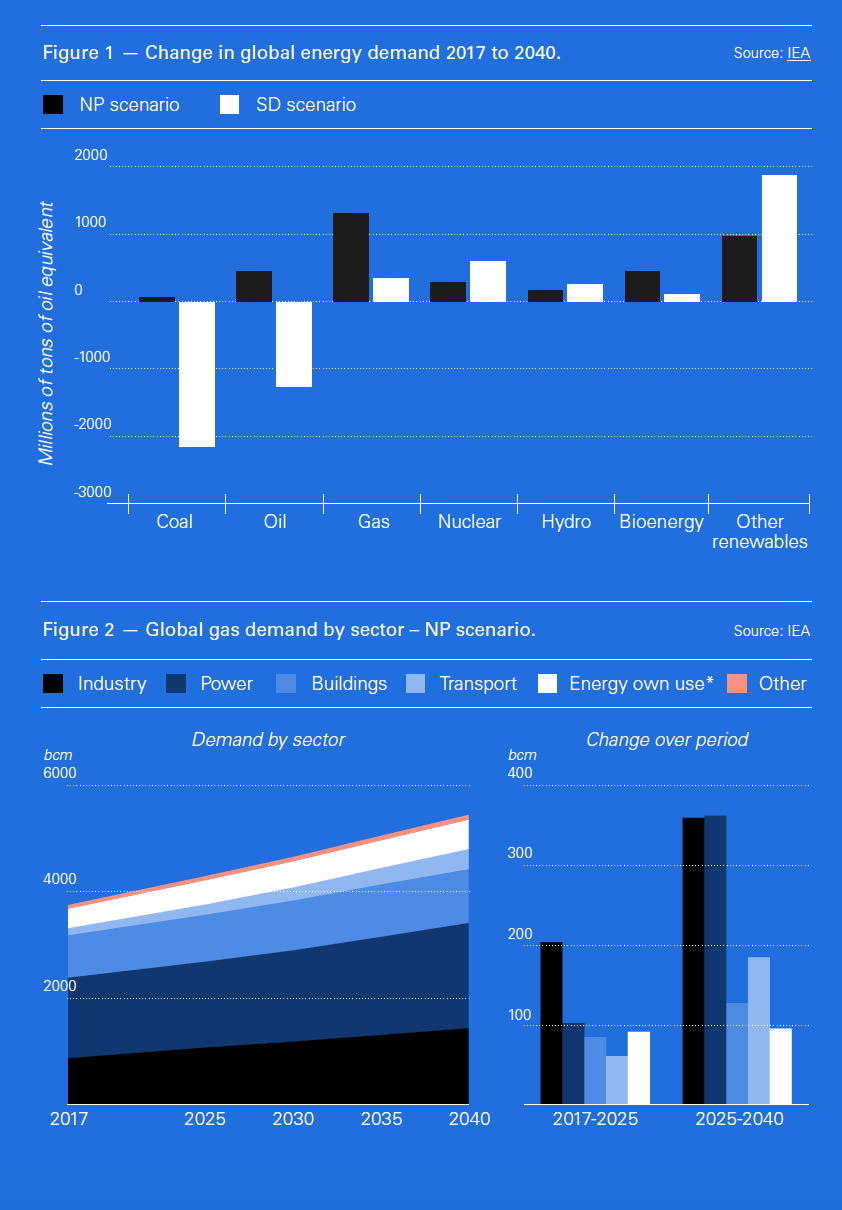

New energy demand will be met by gas, wind and solar, bioenergy, oil, nuclear and hydro, in that order except for coal which will not see any growth as demand plateaus below its 2014 peak (Figure 1). This means that CO2 emissions will continue to grow.

As a result, the NPS scenario will not meet Paris goals. This can be achieved by implementing accelerated clean energy transitions as envisaged in the SDS scenario pathway, with huge reductions in coal and oil, a little more gas and a lot more renewables and nuclear. The net outcome would then be that global energy demand would stay at 2017 levels.

In all scenarios Asia becomes the main destination of future global energy trade flows, with the shift felt across all fuels and technologies, as well as in energy investments. WEO 2018 concludes that Asia's share of global oil and gas trade will rise from around half today to more than two-thirds by 2040.

The future of gas

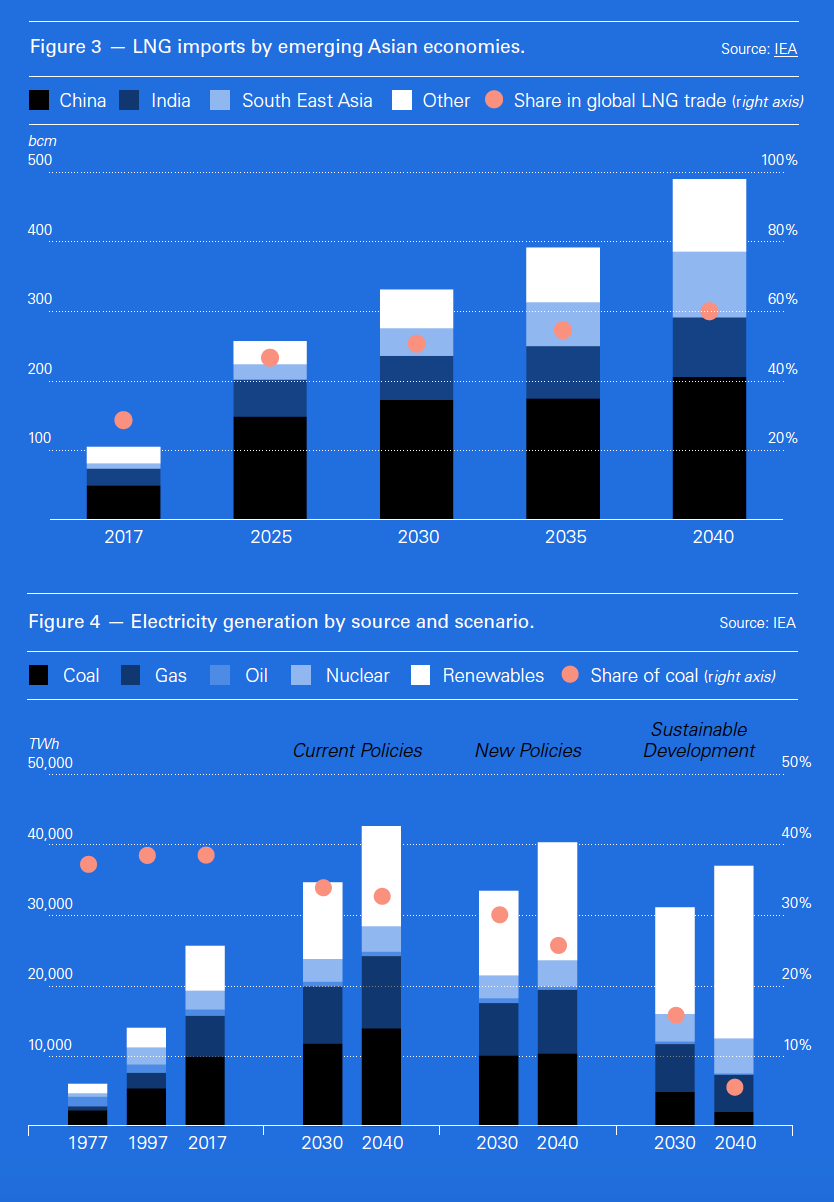

Natural gas will be the fastest growing fossil fuel, overtaking coal by 2030 to become the second-largest source of energy after oil. With demand growing by 1.6%/yr, gas demand will almost be 45% higher in 2040 than today. Industry takes over from power generation as the main sector for growth (Figure 2).

The gas market is becoming global and demand rising, with China emerging as a giant consumer. The IEA expects China’s gas demand to triple, reaching 710bn m³/yr by 2040. However, policy changes in October and increasing security of supply concerns may impact this projection.

Emerging economies in Asia as a whole account for around half of total global gas demand growth, with their share of global LNG imports doubling to 60% by 2040 (Figure 3).

Unconventional gas accounts for more and more future natural gas supply, with US shale development on track for huge growth in the coming decades. Shale gas production will expand by 770bn m³/yr in the period to 2040, which exceeds growth in conventional gas production. US shale production has the potential to account for about half of global oil and natural gas growth by 2025.

Unconventional gas accounts for more and more future natural gas supply, with US shale development on track for huge growth in the coming decades. Shale gas production will expand by 770bn m³/yr in the period to 2040, which exceeds growth in conventional gas production. US shale production has the potential to account for about half of global oil and natural gas growth by 2025.

The movement towards a more interconnected global gas market, as a result of growing trade in LNG, intensifies competition among suppliers while changing the way that countries need to think about managing potential shortfalls in supply. In fact LNG provides most of the growth in global gas trade, with its share increasing from 42% in 2017 to almost 60% by 2040. LNG import flows continue to go mostly to Asia.

The outlook for new projects is more optimistic, as liquid, flexible and transparent trade allows market risks to be spread more evenly among stakeholders and along the value chain.

However, the IEA highlights two imperatives if the future of gas is to be assured: first is its competitiveness against other fuels; and second is better environmental credentials through concerted efforts to reduce methane emissions and to decarbonise.

Outlook for renewables and electricity

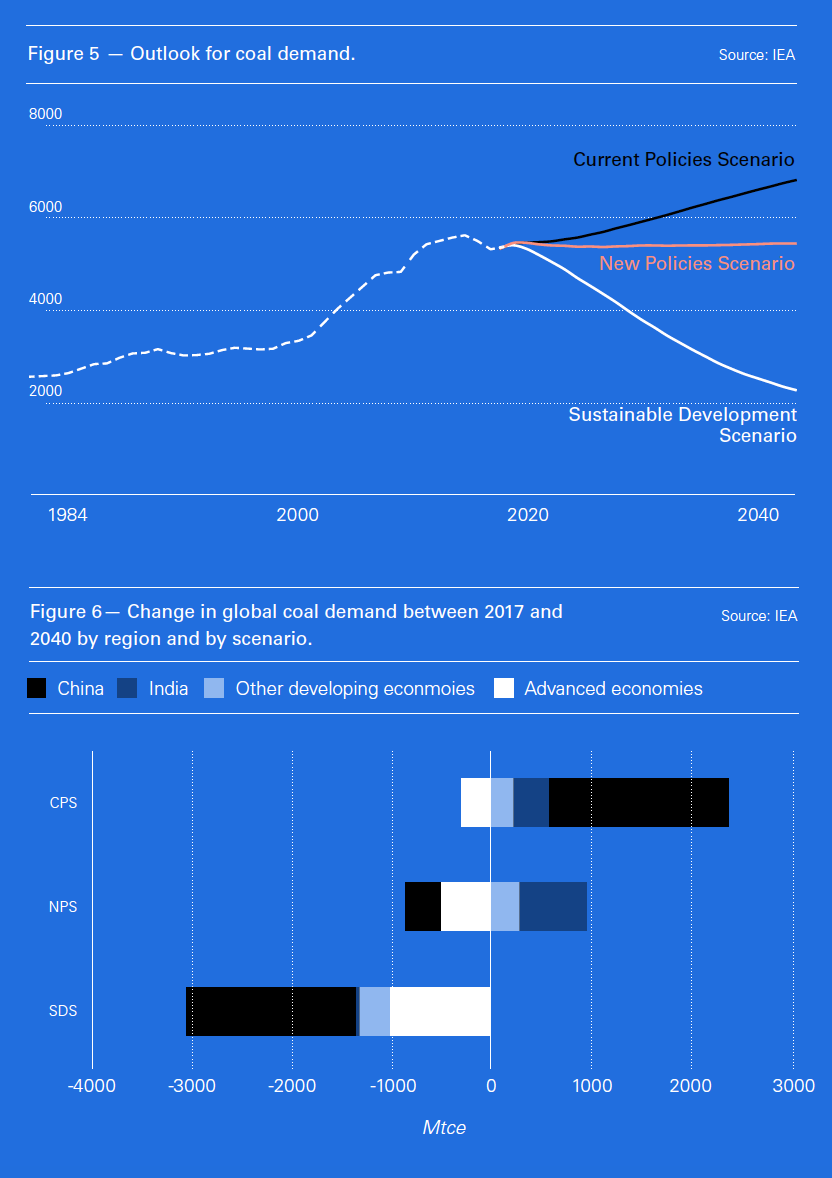

In power markets, renewables have become the technology of choice, making up almost two-thirds of global capacity additions to 2040, driven by falling costs and supportive government policies. This is transforming the global power mix, with the share of renewables in generation rising to over 40% by 2040 in the NP scenario, from 25% today (Figure 4), with the main contributions from:

- Solar PV. This is charging ahead, forecast to expand from 2% of generation today to nearly 10%.

- Wind, which is expected to grow from 4% to 12% of global electricity generation.

- Hydro will remain the biggest source of clean electricity generation, at 15%.

The costs of solar PV and wind will continue to fall, becoming more affordable, but create additional requirements for the reliable operation of power systems.

The IEA warns that even though this expansion brings major environmental benefits, it also brings a new set of challenges that policy makers need to address quickly. With higher variability in supplies, “power systems will need to make flexibility the cornerstone of future electricity markets in order to keep the lights on.”

The issue is becoming of growing urgency as countries around the world are quickly ramping up their share of solar PV and wind, and will require market reforms, grid investments, as well as improving demand-response technologies, such as smart meters and battery storage technologies.

Battery storage costs will continue to decline rapidly, with the market growing fast, helping overcome short-term intermittency. But, at 153 GW, pumped storage hydropower comprises the majority of the capacity to store electricity, accounting for 2% of the world’s total.

Electricity markets are also undergoing huge transformation with higher demand brought by the digital economy, electric vehicles and other technological change. Global electricity demand will grow 2.1%/year in the period to 2040, mostly driven by rising use in developing economies. Between now and 2040, nearly 90% of electricity demand growth will be in developing countries, with China and India at the forefront.

But electrification will have a negligible impact on carbon emissions, unless it is accompanied by stronger efforts to increase the share of renewables and low-carbon sources of power.

This happens in the SD scenario, where wind and solar grow very fast, expanding nine-fold to 2040. As a result, low-carbon sources meet around 85% of electricity demand, with gas meeting most of the remainder (Figure 4).

The IEA says that the world is electrifying, but at different speeds and on different scales. The potential for further electrification is huge: 65% of final energy use could technically be met by electricity, while today’s figure is only 19%. In order to focus attention, it introduced another scenario, the ‘Future is Electric’ scenario (FiES). In this further electricity growth is achieved through electrification of services now relying on fossil fuels, so that electricity meets more than 30% of final energy use. It concludes that electricity is becoming the ‘fuel of choice,’ which implies that governments that cannot provide it reliably are weakened.

Outlook for coal

WEO 2018 indicates that coal will remain a key fuel to provide heat and power through to 2040, but new capacity additions have slowed down considerably.

Even though in the NP scenario coal demand is expected to remain flat in real terms (Figure 5), it will still provide the largest contribution to the global power mix, when solar, wind and hydro are considered separately. However, with increasing global energy demand, its percentage contribution will decline from two-fifths now to just a quarter.

The IEA says that coal use would fall in the US, EU and other developed countries. China would also see a decline of 13% by 2040. But these declines would be offset by rising demand primarily in India, where coal demand will more than double by 2040, and in other countries in Asia (Figure 6).

This, though fails to recognise that the rising penetration of cheaper renewables is hitting coal use in India, to the extent that not all of India’s planned new coal capacity will be built.

However, as the IEA points out: “The demise of coal has been widely predicted and consumption fell for two years straight from 2015, but bounced back in 2017…. Recent trends provide a reminder that coal demand could be more resilient than some expect, especially among developing economies in Asia.”

If the most optimistic, SD scenario, is to prevail, coal demand would be required to decline rapidly, starting now (Figure 5). In SD, as the IEA says, “coal moves to the back of the pack”, with demand by 2040 falling back to 1975 levels. Massive declines in coal demand will be needed everywhere: China, India, Other Developing Economies and Advanced Economies (Figure 6). This would lead to CO2 emissions from coal-fired power generation falling by 90% by 2040.

Carbon emissions

The IEA concluded that almost all of the world’s carbon budget up to 2040 will have been used up by existing power stations, vehicles and industrial facilities. Birol said: “We have no room to build anything that emits CO2 emissions.” In other words all new energy projects would have to be low-carbon, which is a major challenge.

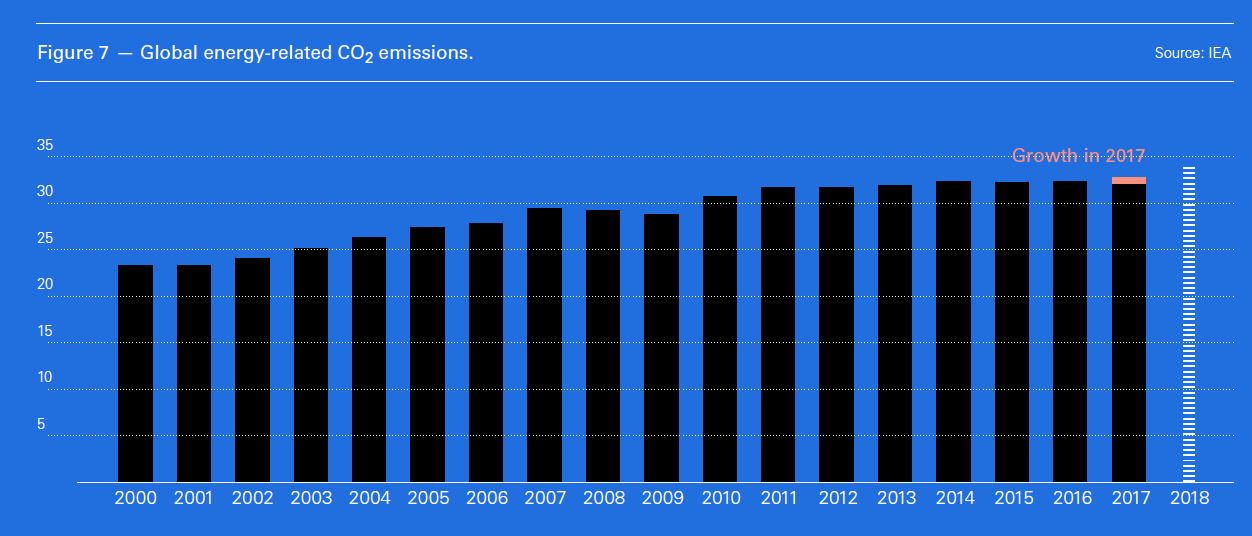

IEA’s NP scenario expects CO2 emissions to rise by close to 11%, from 32.5 gigatons in 2017 to 36 gigatons by 2040. This, Birol says, indicates that unfortunately the emissions plateau observed in 2014 to 2016 was a blip caused by stagnation in the global economy. Without change, what is being observed in 2017 to 2018 is shown in the NPS scenario to be becoming the new norm.

Global energy-related CO2 emissions rose by 1.6% in 2017 and data so far suggest continued growth in 2018 (Figure 7), far from a trajectory consistent with climate goals. This is a major blow to hopes the world might have turned the corner on tackling climate change, and to the belief that economic growth has decoupled from energy demand growth and emissions.

With its dependence on coal, India will overtake the US to become the world’s second-biggest CO2 emitter from its growing power sector, with emissions rising by 80% by 2040, as its electricity demand skyrockets.

These challenges are coming at a time when the UN Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warned, in its October Special Report, that the ‘impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways’ will cause far reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society.

The SD scenario

Worryingly, WEO 2018 concludes that the world is still a long way from meeting the Paris goals on climate change and air pollution. However, IEA’s SD scenario shows how the world can change course to deliver on the Paris goals, limiting warming to ‘well below 2 °C’. It recommends that a "systematic preference for sustainable energy technologies" will need to be applied worldwide.

Through its SD scenario, the IEA presents an energy transition where renewables and energy efficiency lead the charge in reducing CO2 emissions as well as reducing pollutants that cause poor air quality.

Renewables become the dominant force in power generation, providing over 65% of global electricity generation by 2040. Wind and solar PV, in particular, soon become the cheapest sources of electricity in many countries and provide nearly 40% of all electricity in 2040. Emissions reduction in transport, industry and buildings are achieved largely through greatly enhanced energy efficiency and increasing levels of electrification of end-uses.

Overall, achieving the SD scenario would require an increase of only around 13% in energy investment globally, relative to NPS, which is modest.

The IEA states that the SDS sets out an ambitious but pragmatic vision of how the global energy sector can evolve in order to achieve Paris goals. As Birol says: “This means that if the world is serious about meeting its climate targets, then, as of today, there needs to be a systematic preference for investment in sustainable energy technologies.”

Challenges

Challenges

While global energy demand continues to shift to Asia, geopolitical factors exerting new and complex influences on energy markets, underscoring the critical importance of energy and supply security.

Under this changing energy environment, governments will have a critical influence in the direction of the future energy system, particularly in terms of ‘pushing’ energy efficiency. WEO 2018 notes that “energy efficiency is a proven way of meeting multiple energy policy goals, but the flow and stringency of new policies appears to be weakening.”

The problem though, is that most emissions linked to energy infrastructure are already essentially locked in. In particular, coal-fired power plants, which account for one-third of energy-related CO2 emissions today, represent more than a third of cumulative locked-in emissions to 2040. The vast majority of these are related to projects in Asia, where average coal plants are just 11 years old and so have decades of useful life ahead of them.

Expanding the use of carbon capture use and storage (CCUS), improving energy efficiency, and where possible retiring power plants early, could all help. But this would need an unprecedented global political and economic effort.

Highlighting the challenge, Birol said the growing carbon pollution was a result of the global economy growing and driving coal, oil and gas use, adding that “Energy efficiency improvements and renewables are not good enough to reverse that.”

Globally, including China and India, the public opinion tide appears to be turning fast, favouring stronger action to mitigate climate change. This is likely to lead to a faster-than-forecast adoption of low carbon and renewable energy, mainly at the expense of coal and natural gas in power generation, and of crude oil for transportation.

Another concern expressed by the IEA is the prospect of a crunch in oil supply in the next decade. Birol said: “The oil markets I believe are entering a renewed period of uncertainty and volatility. One of the things that worries me is the links between energy and geopolitics are getting tighter and more complex.” This relates mostly to oil but, through oil-price-linkage, it could also impact prices and increase volatility in the global gas markets.

As a result, the IEA recommends, in its specially released ‘Outlook for Producer Economics 2018’ report, that major oil and gas producer countries, having experienced many upheavals in recent decades, will need renewed commitment to reform and economic diversification in the years to come.

Many claim that IEA’s scenarios and recommendations are inconsistent, failing to anticipate change. However, as the IEA points out, the science around emissions trajectories and climate implications is still evolving. As a result, it is inevitable that its scenarios will continue to be updated in light of the latest science, but also in response to changing government policies.

Others claim that investment in new oil and gas fields, beyond those that are already in operation, is not consistent with the Paris goals, and that the IEA does not appear to be taking this on board. But that ignores IEA’s SD scenario, which proposes a possible but challenging pathway to achieve Paris goals. And there are also practical challenges. Renewables are not yet delivering the results expected of them, while the transition needs to be smooth and reliable, the lights kept on and energy affordable, everywhere. These goals need other fuels.

With over 70% of global energy investments to be government-driven, governments everywhere need to take the lead to achieve the IPCC targets to contain global warming, with policies that will change fuel and other energy consumption habits. Without a major shift in policies, energy demand and energy consumption habits will not change easily. In the meanwhile, the energy sector has an obligation to ensure enough energy supplies are available dependably as required by the world.

It should be noted that IEA’s NP scenario describes where present policies are taking us – it is based on existing and officially announced policies and targets. It is clear from WEO 2018 that these will not meet Paris goals. A low-carbon future needs an SD pathway.