The Economy-Environment Tug-of-war [NGW Magazine]

The International Energy Association (IEA)’s 2019 report on renewable energy, giving scenarios out to 2024, said this would be a record year for new solar, wind and other renewable power generation worldwide.

Further, solar PV and wind would account for 70% of the capacity added by 2024. But while global emissions will fall this year, it will not be because of a rapid take-up of renewable capacity.

In its April review of the impact of the Covid-19. the IEA concluded that renewable energy would rise by only 1% from 2019. Given an expected contraction in energy demand of 6%, this may be seen as a good outcome. Nevertheless, it is well below last year’s forecasts, even at a time when fossil fuel demand is expected to be down by 5%-9%.

There are also warnings that the economic slowdown caused by the pandemic may be hampering the shift to renewables. Oxford University’s energy economics professor Dieter Helm points out that governments will put clean energy projects to the back of the queue, after they have already borrowed heavily to deal with the social and economic problems.

Helm says there is no money left: consumers will not be able to absorb the extra cost in their electricity bill.

A prolonged period of cheap natural gas could also be a challenge for renewables. The IEA executive director Fatih Birol told the FT he is concerned that cheap oil and gas could harm the transition to clean energy: “Life for renewables may be even more difficult.”

But despite the difficulties brought about by the crisis, energy ministers – including Amina Mohammed, deputy secretary-general UN, and Frans Timmermans, executive vice-president European Commission – at a recent IEA roundtable discussion remained committed to supporting key areas of clean energy as they draw up plans to revive their economies after the worst of the pandemic has passed.

These include energy efficiency, wind, solar, batteries, hydrogen and CCUS. They called for making investments in clean energy a key part of Covid-19 response and recovery plans.

This is what the Global Renewables Outlook 2020 report, released by the International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena) in April – based on data to the end of 2019 – argues: that advancing the renewables-based energy transformation is an opportunity to meet international climate goals while boosting economic growth.

Introducing Irena’s first Outlook, its director-general Francesco La Camera said “the European Green Deal, to take an existing example, shows how energy investments could align with global climate goals.” He added: "The time has come to invest trillions, not into fossil fuels, but into sustainable energy infrastructure."

Global Renewables Outlook

He said stimulus and recovery packages will be at a scale to shape societies and economies for years to come and so they have to align with medium- and long-term priorities, including the UN 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement.

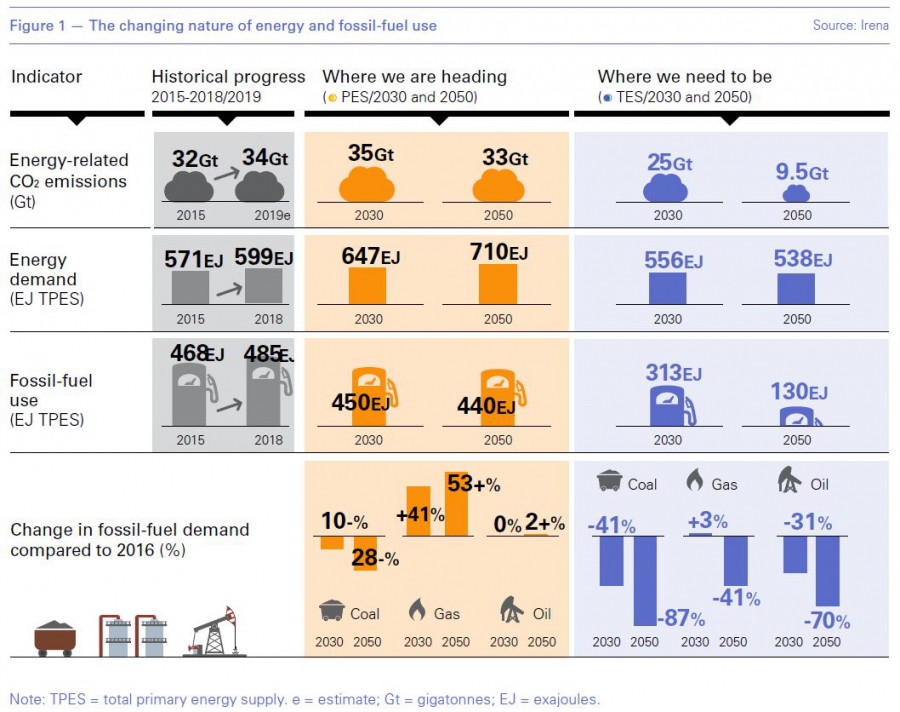

The Outlook highlights investment options until 2050 and the policy framework needed. But it also requires stimulus and recovery packages to “accelerate the shift to sustainable, decarbonised economies and resilient inclusive societies” and provides a renewable energy roadmap (Figure 1), based on two of Irena’s scenarios. These are a planned energy scenario (PES) and a transformed energy scenario (TES). PES is based on current energy plans; and TES is focused on limiting global temperature rises to well below 2 °C.

TES requires slashing fossil fuel use by about three quarters by 2050. In terms of natural gas, TES allows a small increase in demand up to 2030, by 3% compared to 2016, but requires a whopping 41% reduction by 2050. Given the increase in gas use between 2016 and now, this actually means that gas demand must be cut by about 7% between now and 2030.

The Outlook shows that energy efficiency and renewable sources will account for 90% of the mitigation measures needed to stay on the right side of the widely-accepted temperature increase limit.

Energy-related CO2 emissions need to fall by 3.8%/yr on average until 2050, to 70% below 2019’s emissions. Moreover, the UN estimates emissions must fall by 7.6%/yr this decade in order to limit global warming to 1.5 °C. But the average annual change over the last decade has been an increase of 1%/yr, which casts doubt on the achievability: this year being an obvious likely exception – but incidental and for all the wrong reasons.

Based on data to mid-April the IEA estimated that global CO2 emissions could decline by about 8% in 2020 year on year. In effect this means that 2020 must be repeated every year to 2030 to achieve the 1.5 °C limit.

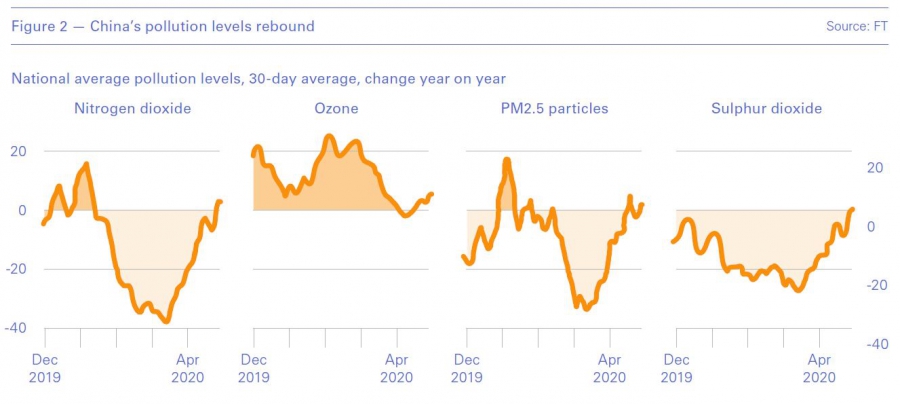

The scale of the problem can be visualised when considering pollution levels in China: between January and early April it had the biggest absolute drop in emissions world-wide. New analysis has found that these have already rebounded to above their pre-crisis levels (Figure 2) as transport and heavy industry come back on. So the climate gains from lockdown are likely to be short-lived.

Irena identified five key technology pillars where extensive progress is required for the future of energy:

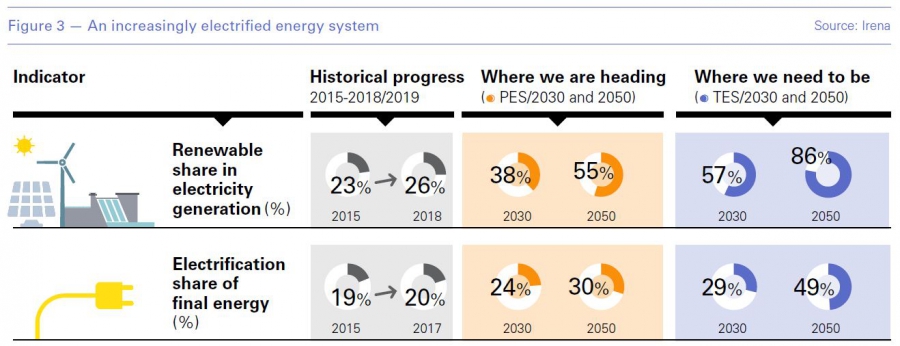

- Electrification, with the rate of growth in the percentage share of electricity in final energy required to quadruple (Figure 3)

- Increased power system flexibility, considered to be a key enabler for the integration of high shares of variable renewable electricity;

- Conventional renewable sources: hydropower and bioenergy;

- Green hydrogen, where demand cannot be electrified;

- Innovation to address challenging sectors.

A key requirement of the Outlook is that fossil-fuel investments need to be shifted to renewables and electricity, with total investment in the energy system in the TES scenario required to reach $110 trillion by 2050, or around 2% of average annual GDP over the period (Figure 4).

Irena put forward another scenario, the Deeper Decarbonisation Perspective (DDP) – over and above TES – to achieve net-zero emissions by no later than 2060. But this would add another $20 trillion, taking the total investments needed to achieve Paris Agreement targets and net-zero emissions to $130 trillion.

In addition to the obvious environmental benefits, Irena states that these investments will also have major socio-economic benefits, such as job creation, people’s welfare and GDP gains, detailed in the Outlook.

The Outlook shows that renewables investment would pay off significantly, with savings eight times more than costs when accounting for reduced health and environmental externalities.

However, despite the significant renewables growth in global power generation so far, the Outlook highlights a widening gap between rhetoric and action – and that was before Covid-19:

- The gap between aspiration and reality in tackling climate change remains as significant as ever.

- The distribution of efforts among countries remains uneven, with some countries lacking policy targets.

- The health, humanitarian, social and economic crises set off by the current Covid-19 pandemic will either widen the gap or accelerate the decarbonisation of our societies.

There are some positive and transformative energy developments:

- There has been widespread adoption of renewables and related technologies;

- Renewable power generation is now growing faster than overall power demand; and

- The electrification of transport is showing early signs of disruptive acceleration.

But one must weigh against those the facts that:

- Renewables are growing slowly in major energy-consuming sectors such as buildings and industry; and

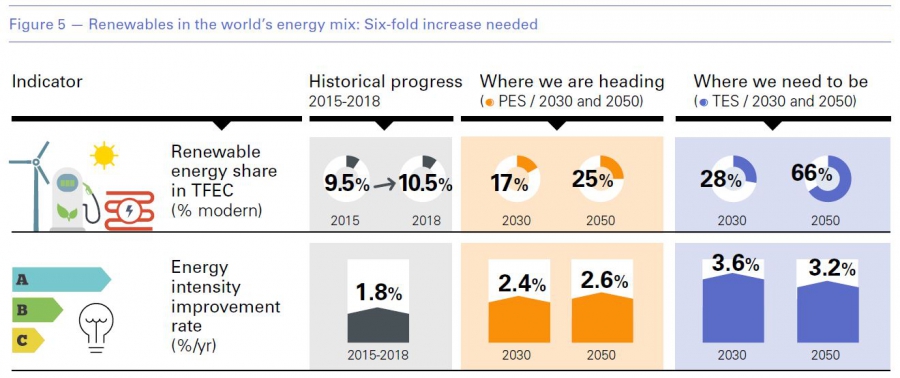

- The share of modern renewable energy in global final energy consumption has been around a tenth since 2010, while a six-fold increase will be needed by 2050 (Figure 5).

Implications for natural gas

Irena points out that while natural gas does have lower carbon intensity than other fossil fuels, it is not a zero-carbon solution. In addition, the problem of fugitive emissions from gas industries is a serious drawback that has not been adequately addressed yet.

Further, projects now being built or planned in the natural gas industry are not consistent with policy objectives of ‘zero’ or ‘net-zero’ emission energy systems. This raises questions about risks associated with investments, chiefly ‘stranded assets.’

Irena proposes that gas systems can be greened using a combination of upgraded biogas, synthetic methane produced from green hydrogen and CO2, as well as direct green hydrogen injection into the grid. Using more hydrogen might help to accelerate a transition.

Irena acknowledges that the natural gas industry is also looking at hydrogen as it extends or repurposes infrastructure, but more work needs to be done.

La Camera said that “price volatility undermines the viability of unconventional oil and gas resources, as well as long-term contracts, making the business case for renewables even stronger. One further result would be the ability to reduce or redirect fossil-fuel subsidies towards clean energy without adding to social disruptions.” An additional benefit is that renewables improve energy security by reducing oil and gas import dependence.

But competition from cheap oil and gas is precisely where the challenge to renewables may lie post-Covid-19.

The IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2019 points out that unless major policy changes are made, society is and will continue to be heavily dependent on fossil fuels, and increasingly gas.

In fact, a three-way race is underway in Asia between coal, natural gas and renewables to provide power and heat to its fast-growing economies and populations.

Challenges

As noted at the recent IEA roundtable discussion, the world has not yet reached a clear picture of the pandemic and its immediate effects, let alone the long-term consequences. Given the urgency of action at least cost, governments and policy-makers are focusing on short-term economic stimulus measures instead of long-term clean technology.

Despite the optimistic outlook for renewables, parts of the world – particularly in Asia – will continue burning fossil fuels including oil, gas, and coal for energy production.

These energy sources will persist in some places owing to a lack of political will, along with the availability of cheap coal and gas. Additionally, the shift to renewables is not happening fast enough to meet electricity demand which is rising even faster.

According to Irena, renewables growth was already slowing down in 2019. Helm points out that if “renewables were not on a path to very quick cost-competitiveness in 2019, the sharp falls of oil, gas and coal prices…have changed the arithmetic further.”

He says that renewable generation advocates “are keen to point to the falling costs of renewables, but less willing to carry the assumption over to fossil fuels, where technological progress in the last decade has been extraordinarily fast,” also bringing costs down – as will post-Covid-19 consolidation and restructuring of the industry.

The pandemic is exacerbating renewables growth challenges by causing disruptions to global supply chains and project execution in 2020. It also poses a serious threat to long-term climate change action by compromising global investments in clean energy and weakening industry environmental goals to reduce emissions.

Birol said the stimulus packages now being prepared by governments around the world provide a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to accelerate the transition: “Yes, we have a major problem with the coronavirus, yes, our economies have to recover but we shouldn’t forget we have another problem: bringing global emissions down.”

According to the IMF, by mid-May governments had put forward “about $9 trillion emergency lifelines in response to the pandemic.” Of this, “direct budget support is estimated at $4.4 trillion globally. Additional public sector loans and equity injections, guarantees, and other quasi-fiscal operations – such as non-commercial activity of public corporations – amount to another $4.6 trillion.” These measures are directed towards getting back to a normal functioning of societies and economies.

As Helm says, “whatever the economic arguments for green investments as part of a large-scale public investment programme, in the post-lockdown world, there will be other pressing claims on national budgets.” Employment will take priority – it trumps environment in politics.

Helm warns that “as long as the total investment budgets for governments are limited, there will be choices and trade-offs to be made. The green deal investments might not turn out to be the highest priority.” So far this appears to be the case.

He added that “policies are likely to focus on consumption rather than investment… and to favour spending on health and related public services rather than the environment.”

In the longer-term demand for renewable energy will continue to grow, driven by declining costs of technology, the need to reduce CO2 emissions, and growing energy demand. But according to BNEF gas capacity will also play a vital role to support the increasing flexibility needs of renewables.

_f900x378_1590398152.JPG)