Texas flaring hits the roof [NGW Magazine]

The astonishing growth of shale oil production in the Permian Basin has overwhelmed the infrastructure needed to gather and evacuate associated gas from oil-directed wells. Huge volumes of natural gas are therefore being flared and vented – with the blessing of the oil and gas regulator, the Texas Railroad Commission (RRC), which supports oil output growth.

With one of the RRC’s three commissioners up for re-election this year, voters are getting their say on the issue, which threatens reputational damage to the US and to natural gas.

Owing at least partly to the Permian, the US has become one of the largest gas-flaring countries in the world. According to World Bank data, it flared 14.1bn m³ of natural gas in 2018 – more than Algeria (9.0bn m³), Venezuela (8.2bn m³) and Nigeria (7.4bn m³). The only countries that flared more were Russia (21.3bn m³), Iraq (17.8bn m³) and Iran (17.3bn m³). These countries are strange bedfellows for the world’s largest and arguably most advanced economy.

Driving the growth in gas flaring in the US has been rapid growth in oil production, primarily oil from shale. Between 2013 and 2018 output grew by more than half to 15.3mn barrels/d (b/d).

Much of this growth has been in just two states: North Dakota and Texas. Both have seen rapid development of unconventional oil plays – the Bakken Shale in North Dakota, and Eagle Ford and the Permian Basin in Texas.

All three of these plays have significant volumes of associated gas production. Even in 2017, the totals in those two states were 10-20 times the volumes reported elsewhere.

Changing sentiment

“Prior to 2017, flaring wasn’t a big topic outside North Dakota,” says Artem Abramov, head of shale research at Rystad Energy, a Norwegian consultancy and analytics firm. “Now sentiment has changed, largely because of the energy transition. A lot of our exploration and production clients want to benchmark their flaring intensity against that of their peers.”

Nowhere is gas flaring and venting more controversial than in the state of Texas, mainly because of the Permian Basin, shared with the state of New Mexico. Output in the Permian has grown so rapidly that it is now the largest oil-producing region in the US. In 2019 its output was close to 5mn b/d, says the EIA, a third of the US total. According to Rystad Energy, gas flaring and venting in the Permian reached an all-time high of 750mn ft³/d in the third quarter of last year.

The issue has become increasingly political, with attention focusing on the state’s oil and gas regulator: the Railroad Commission (which long ago ceased regulating the railways). It has come under fire for never refusing to grant gas flaring and venting permits.

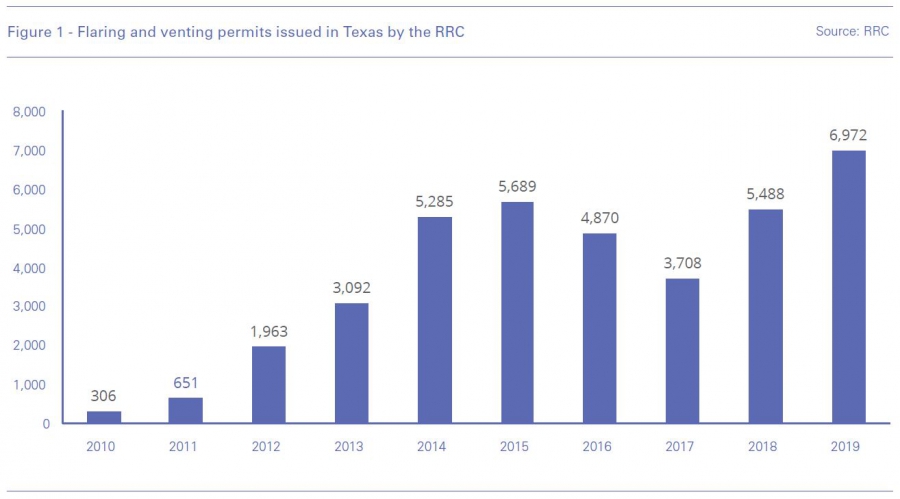

As the chart above shows, the regulator granted almost 7,000 permits last year – an all-time high. Consequently, the RRC stands accused of failing in its duty to prevent the waste of natural resources.

Public poll

Public opinion is being tested in 2020 because one of the RRC’s three commissioner posts is up for re-election in November. Already the Republican incumbent – Ryan Sitton, a strong supporter of allowing flaring and venting to boost shale oil output – has been ousted. In the Super Tuesday primaries March 3, he lost out to his Republican challenger, James Wright, who won 56% of the vote.

However, the real test will come in November, when Wright comes up against the Democrat contender, who has yet to be decided. On Super Tuesday, of the four candidates, it was Chrysta Castaneda, a Dallas-based attorney, who won the most votes: 34%. However, because she did not get 50% of the vote she now faces a run off in May against the candidate that came second, Roberto Alonzo, who got 29%.

Castaneda has made gas flaring and venting the centrepiece of her campaign and she is confident that she stands a good chance of being elected in November:

“Clearly Texans want a change at the RRC, which explains the results on both sides of the ballot,” she tells NGW. “I was very pleased to come in first on the Democratic side and we are headed for a run-off on May 26.

“It makes no sense that we are spending billions of dollars to get energy and then setting it on fire the minute it’s out of the ground. There is a critical need for the RRC to begin enforcing the laws that have been on the books for 100 years against the flaring problem.”

Casinghead gas

State-Wide Rule (SWR) 32 of the Texas Administrative Code allows an operator to flare gas while drilling a well and for up to ten days after a well’s completion. It prohibits venting and flaring of gas under most other circumstances unless authorised by the RRC. Most of the permit requests the commission receives are for flaring associated gas from oil wells, also called “casinghead gas”.

The commission says flaring of casinghead gas may be necessary for extended periods if a well is drilled in a new exploration area, where pipelines are generally not constructed until a well's productive capability is known. Other reasons include: gas plant shut-downs; repairs to compressors, gas lines or wells; or other maintenance. Flaring may also be necessary in established production areas because pipeline capacity is insufficient.

“There are situations in which safety requires that you engage in either flaring or venting of gas,” says Castaneda, “but not as a routine – all day, every day. My key objective is to see us reduce flaring as soon as possible. There are alternatives that can be deployed, even without pipeline capacity, such as on-site electricity generation. I want to encourage every operator who is flaring gas to decrease the amount they are flaring and those who are not generating their own power on-site to do so for at least their own needs.

“In Texas and North Dakota, even though it’s against the law to flare more than ten days after a well is brought online, exception permits for flaring are just handed out routinely on consent dockets without opposition.”

Controversy was ramped up last year when the RRC allowed a producer called Exco to continue flaring and venting on economic, rather than technical, grounds.

The company wanted a permit to flare gas from wells in the Eagle Ford shale, even though there was the option of connecting to gathering pipelines operated by Williams. Exco argued that Williams wanted to charge an unreasonable tariff. Despite a challenge from Williams, the RRC approved Exco’s request last August.

Unusually, the decision was not unanimous. One of the RRC’s three commissioners, chairman Wayne Christian, voted against, expressing concerns that too much gas was being flared for reasons of convenience rather than necessity.

Undaunted by the outcome, in November Williams filed a petition for judicial review of the regulator’s decision in the Travis County district court.

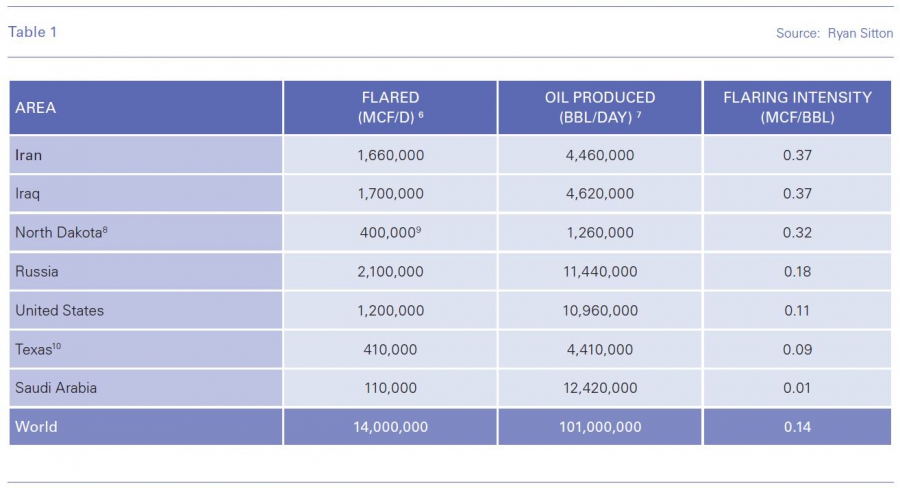

Ryan Sitton is adamant that the RRC’s policy position is appropriate. In a report published earlier this year, he argues that: “With flaring intensity levels in Texas already lower than most parts of the world, and lower than historical levels, a forced reduction could cause a disproportionate increase in flaring in other parts of the world, and have a chilling effect on Texas energy development with no quantifiable benefit to Texans or the world.”

To back up this argument, the report contains the table above. Sitton asserts that in terms of flaring intensity – gas flared/barrel of oil produced – Texas is “well below historical levels and most of the rest of the world”.

However, the report contains inconsistencies. For example, the figure of 410mn ft³/d of gas flared in Texas in 2018 does not tally with his assertion elsewhere in the report that “reliable data [from the Energy Information Administration] suggests that Texas oil and gas operators flare volumes were in the 650mn ft³/d range in 2018.”

More generally, there is disagreement over how much flaring and venting actually takes place in Texas. Sitton claims that only 2% of the gas produced in Texas is being flared and vented. Rystad Energy is unconvinced: “The RRC should focus on ensuring that the industry reports waste gas correctly,” says Abramov, “because we are aware of many companies, typically smaller private operators, reporting that they don’t flare any gas. We know that’s impossible. So we don’t have full visibility in public data. The RRC itself doesn’t have full visibility, so incomplete data sets may be affecting their decisions.”

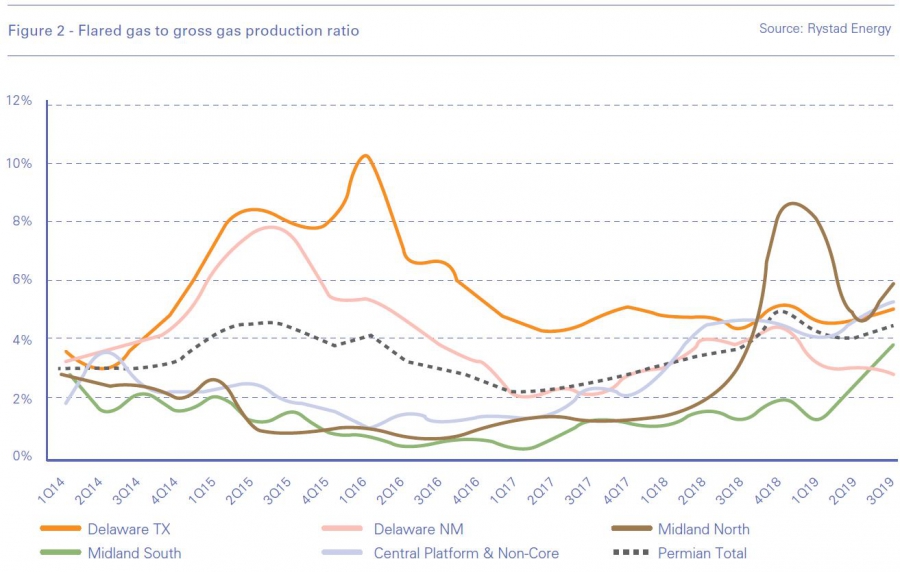

Analysis of collated data by Rystad Energy, illustrated in the chart below, indicates that around 4-5% of gross gas production has been flared and vented in the Permian Basin since the fourth quarter of 2018 – more than double the level suggested by the RRC.

Much will now depend on what voters decide in November. If Chrysta Castaneda is elected as RRC commissioner, her position is plain: “Oklahoma reports zero flaring. New Mexico is on its way to zero flaring. The Texas Railroad Commission needs to start enforcing its own laws and get on board.”