Supergrid threatens Southeast Asian LNG demand

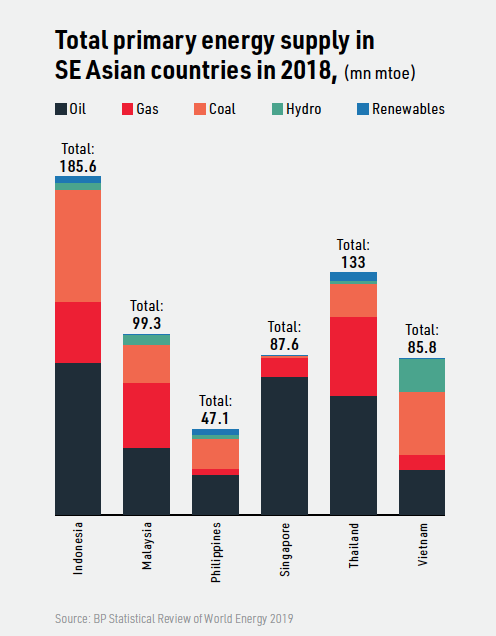

Gas has been a mainstay of the Southeast Asian energy economy for decades, with production of the fuel rising strongly as its share of the rapidly-growing regional power generation and industrial markets increased. By 2000, gas accounted for more than two-fifths of the region’s electricity and around a fifth of its total primary energy supply.

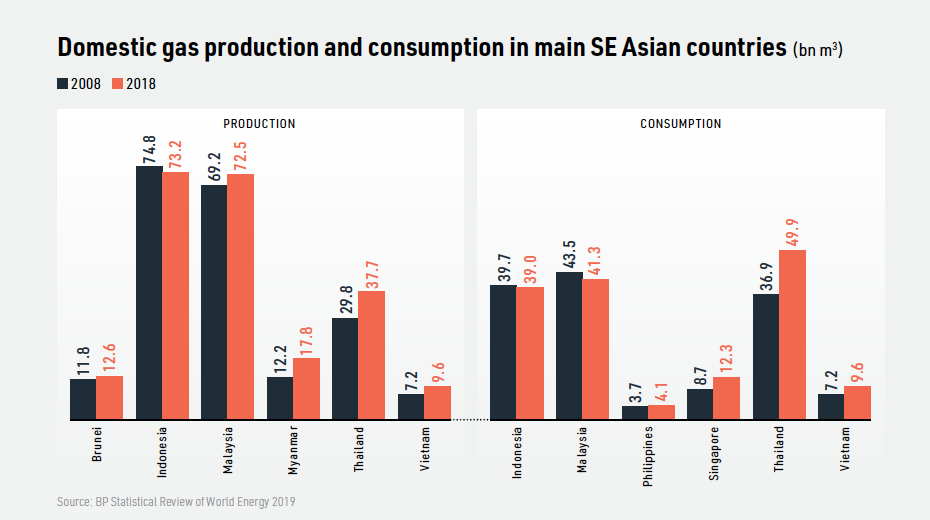

Three Southeast Asian countries also became significant exporters of gas in the form of LNG. By 2008, Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei together exported 67.6bn m3 of LNG, which accounted for almost a third of regional gas production and 29% of global LNG sales.

However, growth in regional gas production slowed significantly from the late 2000s, with output of 223.4bn m3 in 2018 only 9% higher than in 2008. In the same year, the LNG exports of Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei totalled 62.6bn m3, with their combined share of the global LNG market halving to 14.5%.

Growing demand

While Southeast Asian gas production and LNG exports were languishing, regional gas use was growing. Consumption in 2018 was 12% higher than in 2008, with part of the demand being met through cross-border pipelines. In 2018, Singapore received 7bn m3 of gas from Indonesia, while Thailand imported 7.8bn m3 from Myanmar. And, from 2011, some Southeast Asian countries began importing LNG.

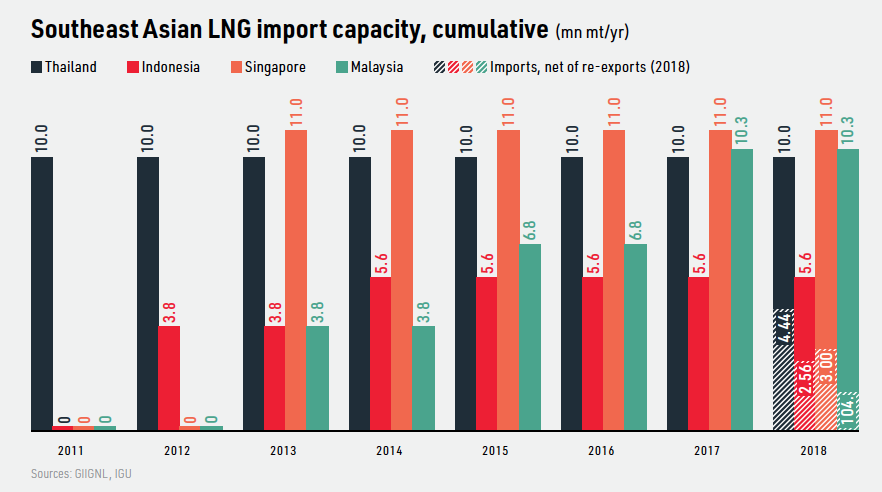

By September 2019, four countries – Thailand, Singapore, and LNG exporters Indonesia and Malaysia -- hosted eight regasification projects with 36.9mn metric tons a year (50.2bn m3) of capacity.

Much of the increased gas use occurred in the electricity sector, even though coal burn grew strongly from the 1990s. According to International Energy Agency (IEA) data, Southeast Asian coal-fired generation quadrupled from 79 TWh in 2000 to over 320 TWh in 2016.

Regional gas-fired generation grew at a lower annual average rate, although this reflected its higher starting point. The 241 TWh increase in gas-fired generation between 2000 (154 TWh) and 2016 (395 TWh) was almost identical to the 242 TWh increase in coal-fired generation over the same period.

Continuing growth

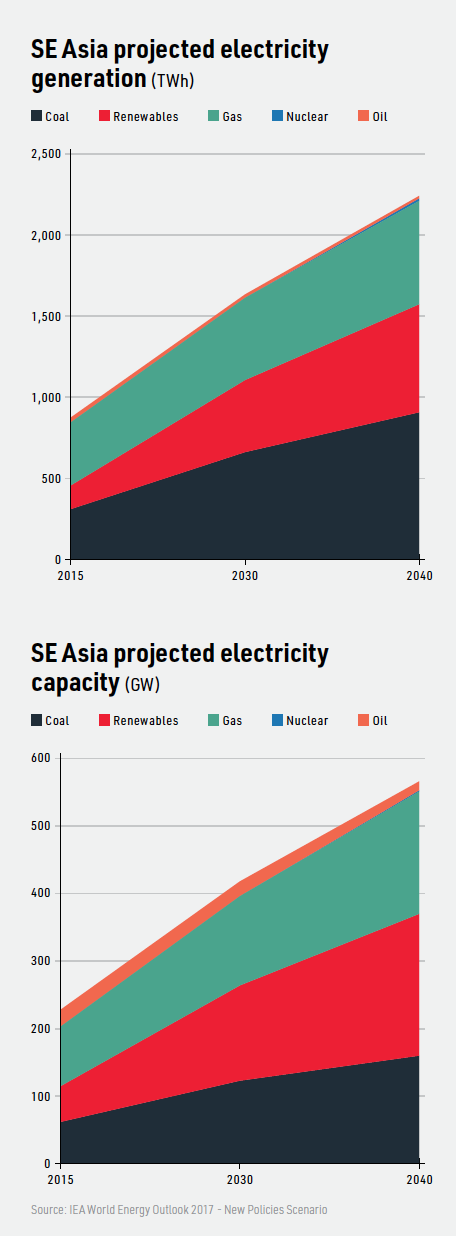

With Southeast Asian economic activity expected to remain buoyant, regional energy and gas demand are forecast to continue growing strongly. The New Policies scenario in the IEA’s latest Southeast Asia Energy Outlook estimates that regional energy demand will increase by almost two-thirds between 2016 and 2040. It also forecasts that gas demand will increase “by around 60% to 2040, due to rising consumption in power generation and industry.”

The scenario envisages that Southeast Asian gas demand will increase by almost 2%/year from 170bn m3 in 2016 to 269bn m3 in 2040. The increase will be driven by 4%/year growth in industrial sector gas use and 1.4%/year growth in gas burn in power plants.

Over the same period, the IEA projects that regional gas production will decline from 223bn m3 to 217bn m3. This implies that, even if all regional LNG exports were to end, Southeast Asia would still require 52bn m3 of gas imports in 2040. With limited potential for piped gas imports, LNG would have to meet most of this demand growth.

Moreover, the level of gas imports forecast by 2040 in the IEA’s New Policies scenario may be on the low side since the projected growth in gas-fired generation is muted by past standards. This partly reflects a big increase in renewable energy generation, but also reflects strong projected growth in coal burn based on its cost advantage over gas.

Coal’s cost advantage assumes limited environmental penalisation of its use by carbon pricing or other measures. It also runs counter to evidence that coal is becoming less attractive to governments, voters and, crucially, lenders in much of the region, regardless of its cost advantage. This is indicated by the fact that the amount of coal-fired capacity under active development in Southeast Asia has fallen sharply in recent years.

That said, regional countries show considerable differences in their attitudes to coal as to much else -- not surprisingly, given their very different development status, electrification rates, fuel mixes and energy market structures. These differences may be reduced if plans to interconnect Southeast Asia’s electricity markets move forward.

Regional power market advances

The technical and economic advantages of an interconnected power grid serving Southeast Asia have been discussed for decades, with the project being formally adopted by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) in 1997.

Linking countries or areas with different diurnal or seasonal electricity demand profiles – such as Sumatra and peninsular Malaysia -- would allow the shared use of generating capacity across jurisdictions, reducing overall capital investment. It would also allow countries to access types of generation not available to them, such as hydropower, or that would be too costly or unviable to build at home, such as large-scale solar power complexes in land-scarce areas.

But despite such advantages, and in common with parallel proposals for a regional gas network, little progress has been made in implementing an Asean-wide grid. A few bilateral links have been built that could form part of the wider grid, but they are relatively small-scale. Only nine links with 5.2 GW of capacity had been implemented by the mid-2010s.

The slow progress relates in part to Asean’s lack of ability to enforce policies across the bloc. This is an issue since the structure of national electricity markets varies widely across Southeast Asia, ranging from fully state-owned operations to liberalised regimes. Creating the mechanisms needed for regional power trading while maintaining national market integrity has to date proved an insurmountable obstacle to implementing an Asean grid.

New impetus

Nevertheless, one multilateral project is now under way on a pathfinder basis, with agreement having been reached to triple to 300 MW the capacity available for power trading on the cross-border lines serving Laos, Malaysia and Thailand.

In tandem with this the Stock Exchange of Thailand signed a memorandum of understanding with the state-owned Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand in September “to jointly study product or platform development to prepare for a wholesale electricity market, paving the way to become the electricity trading hub of Asean.”

The Asean and wider Asian power interconnection projects registered another advance in late September when the China-based Global Energy Interconnection Development and Cooperation Organization (Geidco) revealed details of 27 key components of the overall Asian Super Grid at a meeting in the Philippines.

According to the official Chinese news agency Xinhua, Geidco costed the overall project at $18.7 trillion to 2050, including $14.3 trillion on generation and $4.4 trillion on transmission. Geidco added that the power movements envisaged in the overall project would broadly flow from west to east and north to south.

Implications for LNG

How might the implementation of a regional power grid affect LNG?

In some respects, it could be a positive development. For instance, LNG terminals developed in concert with adjacent gas-fired generating plants could avoid the need for the construction of gas pipelines to demand centres if power could be wired there instead.

This could avoid pipeline construction in difficult terrain, potentially achieve capital cost savings, and underpin project development through contracts with creditworthy customers distant from the coastal site.

But it might not all be good news. The transmission of large amounts of power from low-cost hydro, renewable or coal-fired complexes in China or elsewhere to Thailand and points south could hit LNG-fired generation in large parts of Southeast Asia. With Chinese banks now the dominant source of capital for Asian power transmission and generation projects, the threat of competition from low-cost power transmitted from the north is far from insignificant.

Australian imports

LNG-based power generation in Southeast Asia could also face competition from imports into the south of the region. Developers are looking at projects involving the export of large amounts of power or other energy commodities including hydrogen from north Australia to Southeast Asia.

One project that could compete directly with LNG-fired power is being developed by Singapore’s Sun Cable. Power would be delivered to Singapore from 2027 through a 3,800-km submarine cable from a 10 GW solar complex near Tennant Creek, Australia. The Northern Territory government gave the scheme major project status in July..png)

Meanwhile, in the East Pilbara region of Western Australia, the Asian Renewable Energy Hub consortium is planning a 15 GW, 50 TWh/year wind and solar project that would include 12 GW currently intended to produce green hydrogen for export and domestic markets. At one stage the developers, who include Vestas and the Macquarie Group, were planning a 6 GW project comprising 4 GW of wind and 2 GW of solar capacity that would export electricity to Indonesia from the late 2020s.

Beyond that, a consortium is looking at plans for an Australia to Indonesia interconnector that would begin construction in 2030 and have optimal capacity of 43.8 GW.

With Southeast Asian gas use set to grow strongly but production showing few signs of revival, there seems little doubt the region will be a substantial and growing market for LNG for at least the next decade. And if national opposition to an interconnected power grid wins out, the potential for LNG to thrive in the region’s still-fragmented energy markets could remain strong beyond then. But, if the regional grid does take off, the long-term prospects for LNG may become much more uncertain, given the potential influx of Chinese power from the north and Australian power from the south.

You can download LNG Condensed Volume 1, Issue 10 - October 2019 - here.