South Korean LNG set for growth [LNG Condensed]

President Moon Jae-in’s election in May 2017 ushered in a radical change in South Korean energy policy. His administration committed itself to phasing out nuclear and coal-fired electricity generation, replacing it with renewable energy.

Since nuclear and coal supply 70% of the country’s electricity, the process was regarded as long-term, with LNG to be the bridging fuel. Power generation accounts for almost half South Korean gas use, all supplied by LNG. The policy was thus seen as offering a substantial increase in LNG imports.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

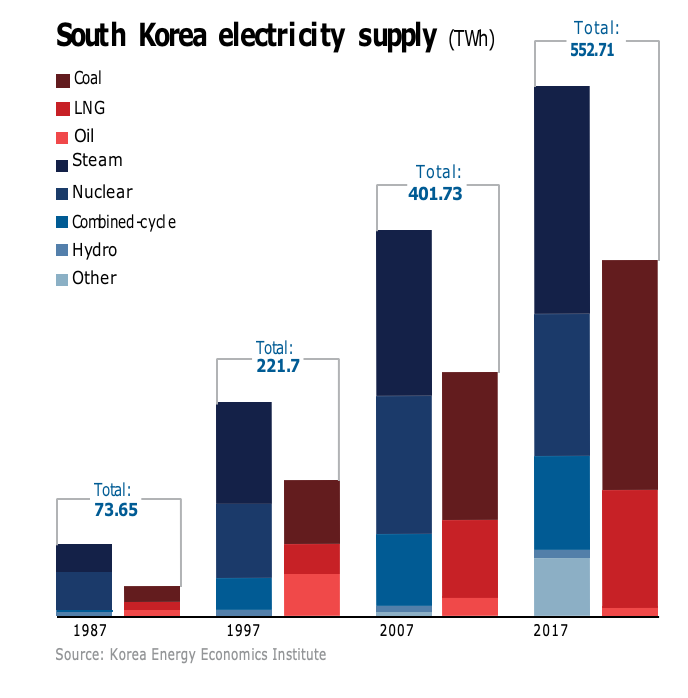

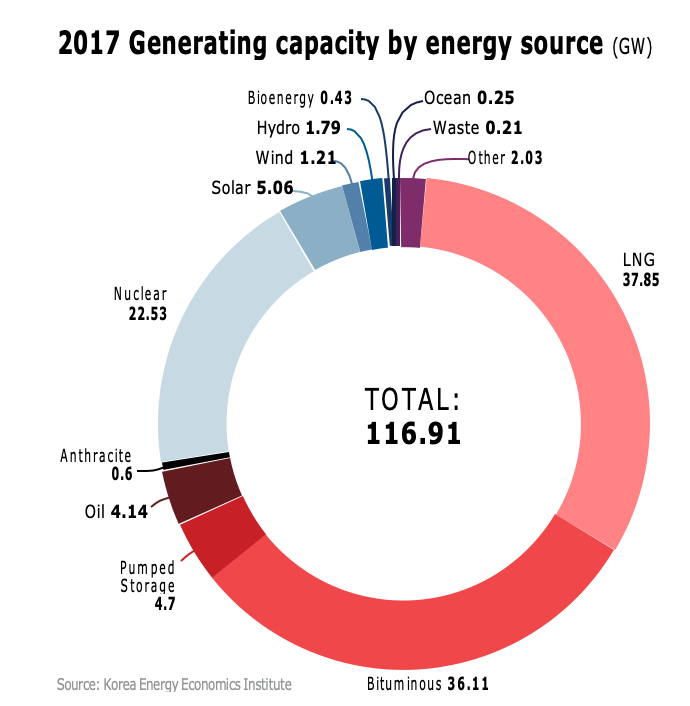

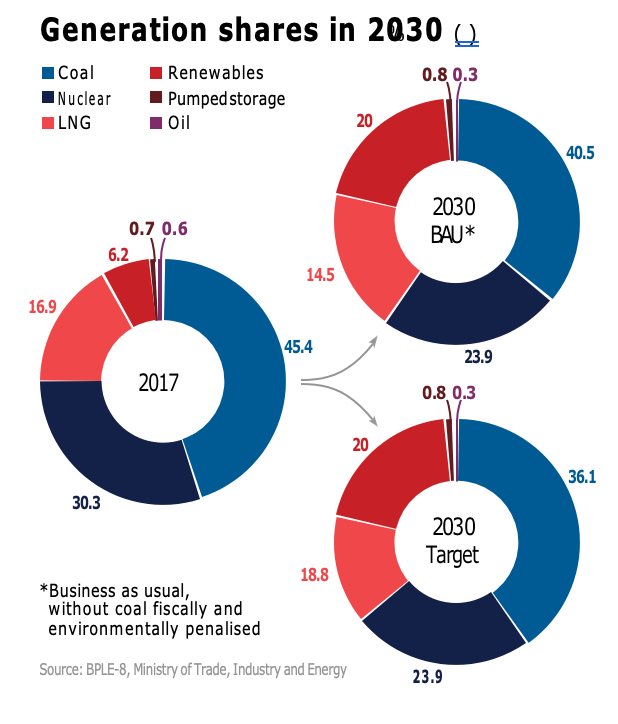

The scale of the replacement needs is indicated by data from the Korea Energy Economics Institute (KEEI). In 2017, coal-fired plants produced 43% and nuclear reactors 27% of the 553.53 TWh of total electricity output. Renewables produced about 6% and LNG 22%. In June 2017, a Wood Mackenzie analyst estimated cancelling all new coal and nuclear plants would require up to 49mn mt/yr of additional LNG.

Long-term electricity projections

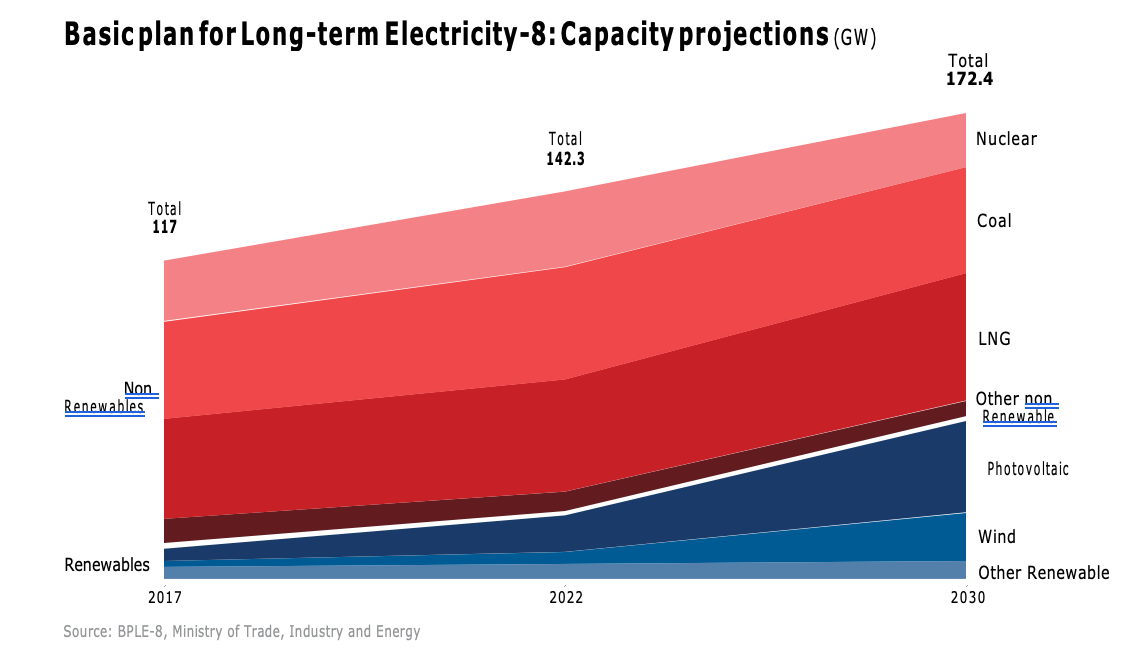

In October 2017, the government issued an energy transition roadmap saying renewables should supply 20% of electricity by 2030. The policy was subsequently embodied in the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy’s eighth Basic Plan for Long-term Electricity (BPLE-8).

Issued in December 2017, BPLE-8 runs to 2031, but focuses on 2030. It includes marked changes from BPLE-7. GDP is forecast to grow more slowly at 2.43%/yr. Electricity use is projected to grow more slowly still – increasing by only 1%/yr to 579.5 TWh in 2030 because of stringent demand-side management measures.

BPLE-8 projects lower coal-fired capacity than BPLE-7. After an initial increase from 36.9 GW in 2017 to 42 GW in 2022, coal plant capacity is projected to fall to 39.9 GW in 2030. The reduction includes conversion to LNG of 2.1 GW of capacity at Dangjin, Taean and Samcheonpo.

Nuclear capacity is projected to fare even worse. After rising from 22.5 GW in 2017 to 27.5 GW in 2022, as plants under construction are completed, it falls to 20.4 GW in 2030 as reactors are closed and newbuilding stalls.

Falling coal and nuclear capacity might be expected to benefit LNG. Gas-fired generating capacity is projected to increase from 37.4 GW in 2017 to 47.5 GW in 2030. However, LNG’s share of electricity output is only projected to rise from 16.9% in 2017 to 18.8% in 2030. And, if coal is not penalised by tax and other “environmentally friendly dispatch” changes, LNG’s share could actually fall to 14.5%.

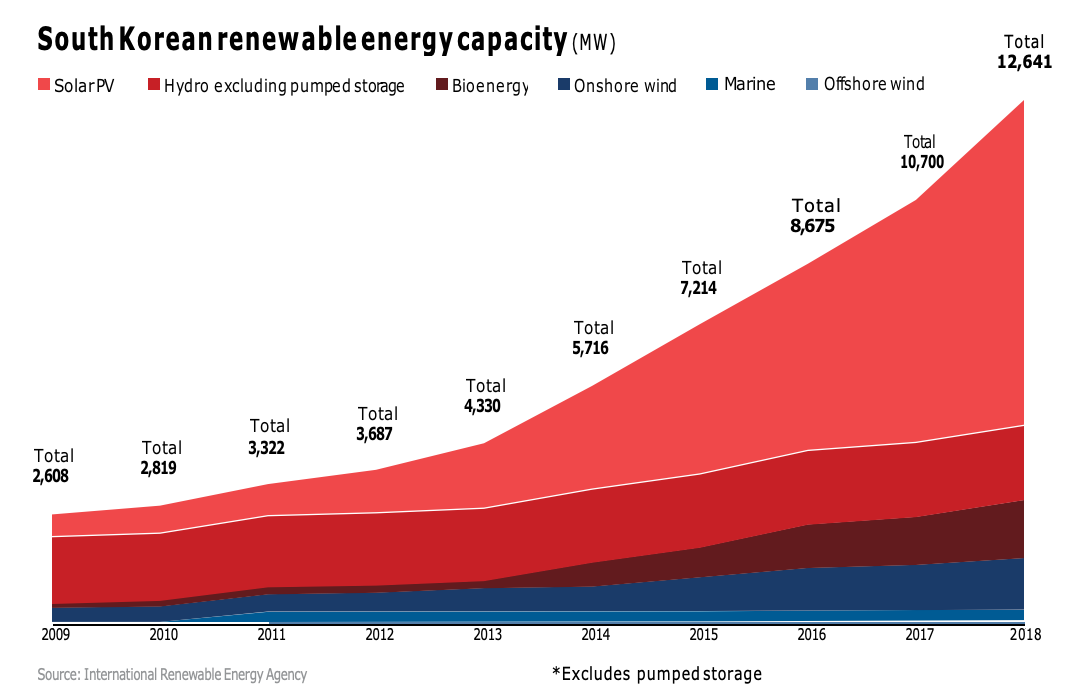

The muted growth in LNG partly reflects the low projected growth in electricity demand. It also results from the forecast jump in renewable capacity from 11.3 GW in 2017 to 58.5 GW in 2030, including 33.5 GW of solar PV and 17.7 GW of wind. Producing 125.8 TWh of electricity in 2030, this would meet the 20% target.

BPLE-8 also noted the proposed Northeast Asian Super Grid would allow South Korea to import power. The Yellow Sea and Peace pipelines to import Russian gas are also under consideration. These initiatives could further adversely affect LNG prospects.

The various threats to gas use were reflected in the country’s thirteenth Natural Gas Plan, issued in April 2018. Demand is projected to grow by 0.8%/yr to 40.49mn mt in 2031. Gas use for generation is forecast to increase by a mere 0.26%/yr to 17.09mn mt.

Recent gas demand trends

How realistic are these projections of gas demand and thus LNG imports? An important consideration is that low expectations for economic activity, electricity demand and gas-fired generation in BPLE-8 and NGP-13 were framed at a time when South Korea was recovering from the mid-2010s energy malaise. This saw gas demand fall from 47.3mn tons of oil equivalent in 2013 to 39.3mn toe in 2015, according to the 2018 BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

But after 2015 there was a marked uptick in activity. Gas demand increased to 42.4mn toe in 2017, according to BP. In 2018, power demand grew 3.6% on-year to 526.15 TWh, according to Korea Power Exchange’s Electric Power Statistics Information System (EPSIS).

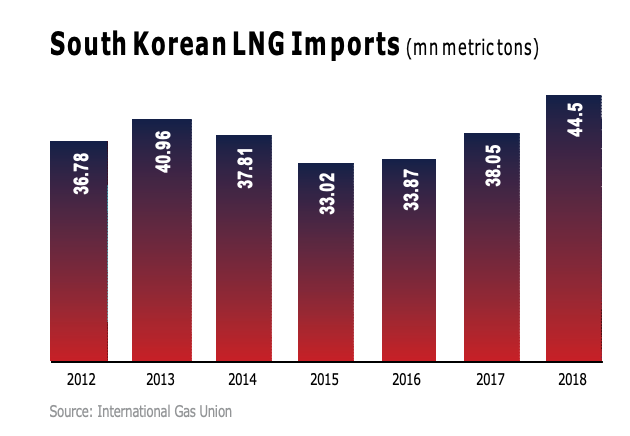

2018 also saw the Korea Gas Corporation’s gas sales jump 12.6% to 36.2mn mt. Within the total, sales to generators rose 19% to 16.4mn mt. Meanwhile, LNG imports surged 17% to 44.5mn mt – already above the NGP-13 projection for 2030 -- according to International Gas Union data.

There are nevertheless question marks over whether the uptick in activity will be sustained. GDP slowed in the second half of 2018 as investment and exports fell, and domestic consumption faltered. As a result, year-on-year GDP growth of 2.7% in 2018 was the lowest since 2012.

The government forecasts GDP growth of 2.6-2.7% in 2019, but other forecasts are less optimistic. The IMF says 2.6% is attainable, but only with a large-scale fiscal stimulus programme. On April 3, the Asian Development Bank trimmed its 2019 GDP forecast for South Korea to 2.5%. More dramatically, the ratings agency Moody’s reduced its forecasts in November 2018 and March 2019, slashing its 2019 forecast from 2.9% to 2.1%, and anticipating growth of only 2.2% in 2020.

The economic downturn is already feeding through into energy markets. Year-on-year LNG imports fell in both January (7.1% down at 3.83mn mt) and February (16.5% down at 3.8mn mt).

Changing demand structure

The economic growth assumptions underlying the muted expectations for LNG in BPLE-8 and NGP-13 are thus in line with current developments. But medium to long-term prospects will depend on developments in the global economy and especially China.

In addition, new tranches of electricity demand resulting from, for instance, the government’s promotion of electric vehicles may also affect overall requirements, while the recent policy shift towards a hydrogen economy also raises uncertainties over electricity and gas demand.

The policy envisages an increase in fuel cell vehicle production from 2,000 in 2018 to 6.2mn in 2040, with hydrogen-filling stations increasing from 14 to 1,200 by 2040. Meanwhile, fuel-cell power generation is projected to rise from 1 GW in 2022 to 8 GW in 2040.

A key issue is BPLE-8’s low elasticity between economic (2.43%/yr) and power demand (1%/yr) growth. South Korean power sales were formerly dominated by industrials. But residential and commercial use has grown from a quarter to almost two-fifths since 1987.

The 3.6% on-year growth in power demand in 2018 was attributed to higher sales to these consumers because of hot summer weather. Industrial demand grew only 2.5% to 293 TWh, according to EPSIS. Residential use jumped 6.3% to a record 72.9 TWh ,while commercial and public use was up 5.1% at 116.9 TWh.

The shift to these consumers may make a higher elasticity more likely. On top of this, a shift in the load curve away from the typically flat electricity demand of industrials to consumers with more variable diurnal and seasonal needs will favour LNG-fired and other non-baseload generators.

Structural changes apart, inter-fuel economics may boost gas demand as tax and other environmental measures erode coal’s competitive advantage over LNG. In the latest round of measures, the government slashed taxes on LNG sales to generators on April 1 from Won 91.4/kg to Won 23/kg ($0.02/kg), while raising the tax on coal from Won 36/kg to Won 46/kg.

Optimistic renewable plans

There may also be problems quintupling renewable capacity to 58.5 GW by 2030, which is much higher than in previous power plans. The renewable fleet has grown relatively slowly to date.

This partly reflects financing and market issues. Wood Mackenzie said in March that South Korea might miss its 20% target for 2030. It said renewables could achieve a 17% share under current arrangements, but only saw 20% being reached if the market was liberalised with, for instance, developers allowed to contract power sales directly with businesses.

While renewables have not been helped by government policies, the sector faces other, perhaps more intractable problems. These include land availability and cost issues, and strong local opposition to many projects. For instance, proposals to install floating solar arrays on 900 water bodies have been fiercely contested and temporarily suspended.

Popular opposition is affecting not only renewables but also coal, with the pollution resulting from coal burn having become an increasing concern over the past year. This may result in the seasonal or permanent closure of more coal-fired plants than assumed in BPLE-8. Meanwhile, popular acceptance of nuclear remains precarious, and will largely be dependent on no major reactor incidents occurring at home or abroad.

The balance of risk is thus that BPLE-8’s expectations for renewable, coal and nuclear generation are too high. Combined with the possibility that its electricity demand projections are too low, the likelihood is that official expectations for gas use in power generation and thus LNG imports over the period to 2030 are also too low.

Quantifying the shortfall is difficult. Last year’s growth in LNG demand is unlikely to be repeated this year, given the international economic climate and the fact that the 17% increase in 2018 included substantial stock building.

But if summers continue getting hotter, renewable capacity growth falls short of plan, coal’s favourable generating economics are reversed and coal plants face continued operational suspensions to reduce air pollution, or there are further unanticipated extended nuclear outages, even low economic and electricity growth could still see LNG demand exceed 50mn mt by 2030.

In a perfect storm, where several of these factors combine, LNG demand could be much higher still.

This article and more in LNG Condensed Volume 1, Issue 4 - April 2019 - Sign Up Free below and never miss an issue:

_f300x384_1558007325.jpg) In this Issue:

In this Issue:

> Sanctions loom over Russian LNG

> Editorial: Off Message in Shanghai

> Feature: Natural gas and the hydrogen economy

> Feature: South Korean LNG set for growth

> Country focus: Colombia: an uncertain market for LNG

> Project spotlight: Delfin LNG: an innovative approach to FLNG and more!

Sign up now to receive LNG Condensed monthly FREE (after filling out the form you will be redirected to LNG Condensed's archive where you can find every issue already published available for download):