Small Dutch fields pose big problem [NGW Magazine]

Under-investment in the so-called “small fields” offshore Netherlands mean that LNG and Russian gas imports will rise faster than foreseen. This in turn will have a strongly negative effect on greenhouse gas emissions – so finds a new report by independent researchers Jilles van den Beukel and Lucia van Geuns published by The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (HCSS) January 27.

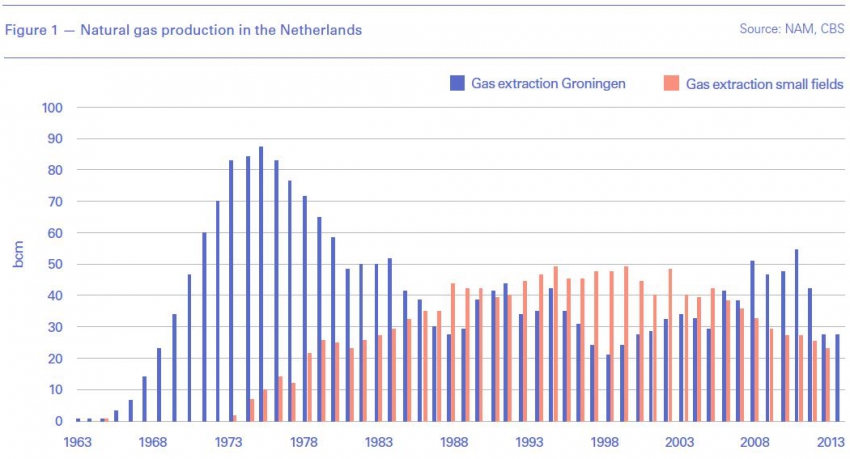

Dutch gas policy has received a lot of publicity in recent years. The Dutch government decided in 2018 to phase out production from the giant Groningen field, which is now expected to be closed down in 2022. Nevertheless, production from small fields – all the other fields – is continuing in the Netherlands, albeit it declining rates since the turn of the century, mainly for geological reason. But they are still expected to deliver some 10 to 12bn m³ by 2030, according to official estimates.

These estimates, however, have been called into question by Van den Beukel and Van Geuns, two well-known Dutch energy analyst with a geological background. In their paper, “The deteriorating outlook for Dutch small natural gas fields”, published by HCSS, an independent geopolitical think tank, the researchers argue that the small fields' production is more likely to be 5bn m³/yr by the end of the decade, and may very well collapse altogether.

Virtual standstill

The researchers note that exploration activity to find new offshore fields has dwindled to a fifth of what it was in 2012. Exploration activity onshore has come to a virtual standstill, even though “there is no geological reason” for this “dramatic decrease.” They observe that the “exploration potential has stayed at a relatively constant level” and there are still “about 200-300bn m³ of (risked) exploration potential from the Dutch offshore.”

The two researchers ascribe this decline in exploration activity to a series of adverse policies from the Dutch government which have shaken the confidence of operators in Dutch gas prospects. These include: a “significantly worse tax regime than in the UK”; regulatory obstacles and delays (they cite the example of a discovery made offshore in 2017 which is expected to see first production in 2023 at the earliest), new very strict environmental legislation banning nitrogen oxide emissions, and strong resistance from local authorities to new onshore exploration and production activities.

These anti-gas measures must be seen in the context of “a (negative) change in the public image of natural gas in the Netherlands,” note the authors. In an earlier paper for HCSS, published in February 2019, Van den Beukel and Van Geuns had observed that the gas industry in the Netherlands has lost its “social licence to operate” as a result of public concerns over induced earthquakes and climate change. The authors see no reason to expect any improvement in the investment climate. “If anything,” they write, “things are more likely to get worse rather than better.”

Negative spiral

The negative political and public sentiments towards natural gas production in the Netherlands threaten to set in motion a negative spiral, the authors warn, as operators become increasingly hesitant to invest in the Dutch gas sector. “It is becoming more difficult for Dutch subsidiaries to obtain funding from international head offices,” write Van den Beukel and Van Geuns. Making matters worse is that gas prices are expected to stay low in the medium term and production costs are likely to go up as “decreasing production results in higher unit operating costs.”

Van den Beukel and Van Geuns further note that a recent “lookback” study from EBN, the state entity that is a non-operating partner in all Dutch gas fields, shows that over the last decades official predictions of future production from the small fields have consistently overestimated real production.

For these reasons, the two researchers believe that the current official outlook of 10-12bn m³/yr of small fields production by 2030 is likely to be far too high. They believe 5bn m3 is more likely and do not rule out the possibility that there will be no Dutch gas production in 2030 at all. They add: “this scenario becomes more likely if natural gas prices stay at the current low levels for an extensive period of time.”

Higher imports

_f500x553_1580724329.JPG)

This is already happening, Van den Beukel and Van Geuns note. From 2014 to 2018 annual Gazprom pipeline exports to Europe increased from less than 150bn m3 to over 200bn m3. In 2018 and 2019, the import of LNG into Europe started to rise significantly. European imports of LNG are now expected to be around 100bn m3 for the 2020-2025 period, double the level of 2010-2017.

Higher imports of LNG and Russian gas not only cost money, they also have a negative effect on greenhouse gas emissions, the authors observe. While lower gas production in the Netherlands leads to lower national greenhouse gas emissions, the effect on total greenhouse gas emissions is the opposite. “Replacing Dutch gas with imported gas results in significantly higher upstream emissions,” the authors note, as Russian gas and shale gas have much higher methane leakage.

In their paper, they calculate that “the replacement in the EU of Dutch gas by Russian gas and LNG negates all progress that has been made by increasing the share of solar and wind in the Dutch power mix.” The authors argue – in a separate opinion piece – that for this reason alone the government should take action to “save Dutch gas production.”

Dutch grid charges face big rise

Electricity and gas network tariffs are likely to surge in the coming decade as the energy transition gets underway in Europe and the Groningen gas field is closed, Dutch industrial users' body VEMW said January 27.

In order to control this cost explosion and tariff increases, a strong effort will have to be made to integrate systems and use efficient flexibility resources, it said, following a presentation made for its members by network operators.

The energy transition means "billions in investments in the electricity networks." State power grid operator TenneT, plans to invest around €5.5bn ($6.1bn) in its high-voltage grids on land and €7bn in the offshore grids by 2030. That compares with the current asset value of €5bn.

Operational costs, in particular for electricity and power, are also rising sharply owing to the shift between supply and demand, with intermittency and decentralisation of production being the most important drivers. The costs for regional network operators are also rising, thanks to the electrification of energy requirements and major investments in infrastructure: €5bn of new infrastructure and €15-25bn of replacement.

The need for natural gas transport will drop with the termination of the domestic Groningen field and substitution by electrification, hydrogen and green gas. The gas transport costs of €800mn/yr nationally and €1.2bn/yr regionally will be borne by fewer parties, who will have to pay more. However the existing infrastructure can at least be used to carry other kinds of gas.

VEMW head Hans Grunfeld said the focus must be on system integration between the various carriers, such as electricity, hydrogen, green gas, heat and CO2, in order to keep tariffs lower. "VEMW argues for the use of all efficient means of flexibility in order to avoid unnecessarily expensive investments. We are pleased that the network operators TenneT, Gasunie Transport Services, Stedin and Liander are entering into open and transparent discussions with us and want to think along with us about taking advantage of opportunities, including a tariff differentiation aimed at removing barriers that frustrate and inhibit the desired energy transition."

Gasunie and TenneT published a study into the new investments needed and the impact of the energy transition on their business January 22, arguing there for close co-operation. Both operators are state-owned.

William Powell