Slovakia keeps options open [NGW Magazine]

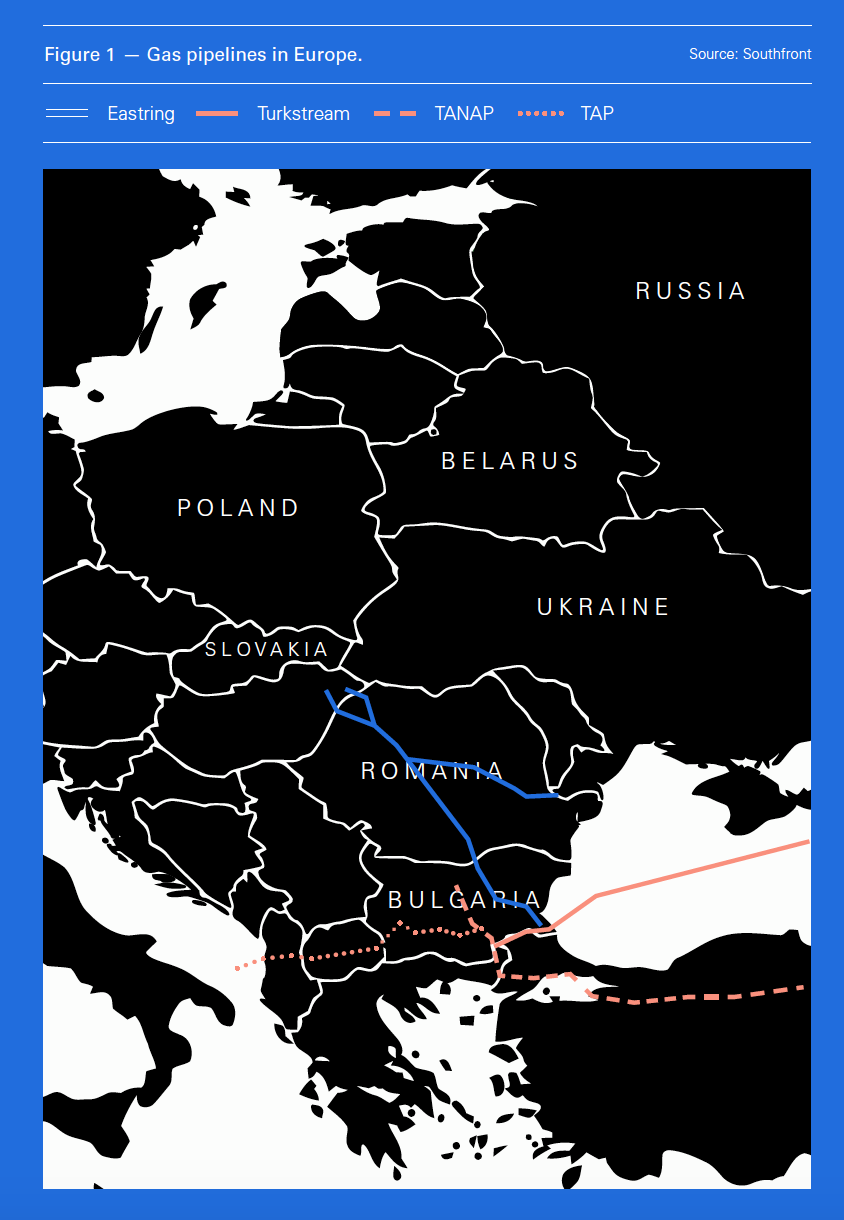

Like other gas pipeline projects in central and eastern Europe, the Slovakia-led Eastring project has been around for some years, rolling with the geo-political punches and adapting to strategic decisions made upstream.

Planned to run south from Slovakia to Hungary and then dive into the Balkans, a feasibility study on the €2.6bn ($3bn) first phase of the project was recently completed. But Eastring is still keen to keep all its options open so that it is not taken unawares.

Just 25 years old, dwarfed by its neighbours, and set on the easternmost edge of the EU, Slovakia has long viewed its vital role in European gas flows as a source of pride and marker of international weight. It owns the EU’s biggest transit pipeline system, capable of transporting some 90bn m³/yr. However, the country is on tenterhooks concerning its nearly €1bn business collecting Russian gas at its eastern border with Ukraine and carrying it westwards to Austria’s Baumgarten hub.

That worry inspired Eastring, but as Russian efforts to circumvent Ukraine as a transit state have ebbed and flowed, so too has the project’s strategy. While Gazprom is unlikely to ditch Ukraine entirely by its pronounced 2019 target, Slovakia still needs to search for new meaning and a new role for its slimmed-down trunkline.

“Slovakia has built itself up as an East-West bridge, and its energy role is key to that,” points out a regional expert in energy markets at Brno‘s Masaryk University, Martin Jirusek.

Double agent

Slovak transmission system operator (TSO) Eustream initially proposed Eastring in 2014, as the EU was in the midst of dismantling Russia’s bid to build the giant South Stream route under the Black Sea to Bulgaria. The project pledged to improve energy security for the isolated Balkan states hard hit by the gas war of 2006 and 2009, when Russian flows through Ukraine were abruptly curtailed in the depth of winter.

That plan helped Eastring secure the status of an EU project of common interest (PCI) under the EU’s Connecting Europe Facility, which aims to help reduce Moscow’s leverage in central and eastern Europe by diversifying supply. However, the project has gone through myriad changes already in its short history.

Eastring even originally considered a brief detour into Ukraine. However, it has now settled on making its way through Hungary. The route it will take after that to/from the Turkish border is yet to be confirmed, although it has memorandums of understanding with Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria.

As well as the route, the role Eastring hopes to play is also less than straightforward. While the project will still offer southeastern Europe an alternative to Russian gas that has crossed Ukraine, it sees flows headed in the opposite directions as its main commercial opportunity.

Russia has replaced the defunct South Stream with TurkStream 2. Eastring hopes to collect gas arriving via the 15.75bn m³/yr second string, likely to launch operations in 2021, to ship it to central Europe.

That would see the project effectively aid the Kremlin’s bid to circumvent Ukraine. But Eastring is a double agent and is also eyeing a role in the EU’s Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) strategy, transporting Caspian Sea flows arriving at Turkey’s western border via the Tanap pipeline to the EU.

“Things have changed significantly since the Eastring project was first proposed,” admits Eustream’s head of regulation and network development Michal Lalik. “The route, the cost, the political background are all different now. The quick development of other pipelines like TransAdriatic Pipeline and Turkish Stream have changed a lot of considerations for Eastring.”

Eustream marketing copy proclaims “Eastring is the only project that offers direct routing between the developed EU markets and the southeast Europe region. As Turkey becomes a major gas hub with excess import capacities, it will look for a way to export surplus gas, while the same applies to the Balkan Gas Hub project in Bulgaria. New sources of natural gas (Caspian & Middle East Gas, TurkStream, LNG) will create an excess of natural gas in Turkey/Balkan region. However, there is currently no infrastructure to transfer this excess natural gas further into Europe.”

Tangled web

Eustream – 51% state-owned but controlled by EPH, the closely-held Czech-Slovak energy holding that owns the remaining shares – announced in September the completion of a feasibility study.

The findings are now being analysed by Eustream. The document suggests that the work of building a 1,200-km line from Slovakia to the Bulgaria-Turkey border could start by 2022, and go online by 2025 with initial demand of 12bn m³/yr. The pipeline would have an initial capacity of 15bn m³-20bn m³, with a potential upgrade up to 40bn m³/yr in a second phase.

The feasibility study earned a grant of €1mn in EU funding, with Brussels eyeing the project’s promise to alleviate the risks of southeastern Europe’s almost total reliance on Russian gas sent via Ukraine.

“[Eastring] offers unique and workable solutions for a single European market,” Eustream claimed in a press release. “It will enhance the EU‘s energy security and strengthen the competitiveness of its natural gas market.”

However, Eustream continues to mull its routing options as it watches the development of the region’s tangled web of planned projects.

“We’re currently analysing the feasibility study,” reports Lalik. “We’re assessing three options of the routing, which differ in all project countries.”

That hints at support for recent unconfirmed Russian media reports that Gazprom wants TurkStream gas bound for the EU to run through Serbia rather than Romania, and then on to Slovakia. Bulgaria and Serbia plan to launch an auction for binding bids for capacity on future pipeline projects by the middle of December, Srbijagas officials were quoted as saying in late November.

“The most realistic route is Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Slovakia running gas from TurkStream to the northwest,” states Jirusek. “Or Romanian gas in the same direction; but then it’s competing against BRUA.”

Another PCI, the 4.4bn m³ BRUA faces the same sort of shifting sands as Eastring as it tries to negotiate CEE’s highly politicised gas pipeline network. Planned to link Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Austria, terminating at Baumgarten, the project is being held up by Hungarian ambitions to make itself a hub for the potential bonanza offered by several major projects in the Romanian Black Sea.

However, Lalik states clearly that Eastring has “no ambition regarding Romanian Black Sea production”.

Sources at Hungarian TSO FGSZ told NGW earlier this year that the currently disused Hungary-Slovakia interconnector could be expanded to 5.2bn m³ to allow Romanian Black Sea gas to make its way to Austria. Eustream confirmed in October that a “successful allocation procedure for the HUSKAT project route” had been held.

Up in the air

One thing that is certain is that Eustream will continue to stress that Eastring’s original purpose still stands. Offering the isolated Balkan markets a link to EU gas is key to securing EU funding.

“Security of supply for the Balkans is important for the EU,” agrees Lalik. However, he points out that Eastring also “needs a commercial impetus.”

Providing transit for Russian and Azerbaijani gas to central Europe is that necessary impetus, the feasibility study asserts. But some contend that neither the commercial nor the energy security cases put forward hold water.

“Although marketed as an answer to current central and eastern European gas supply security challenges, the Eastring pipeline is actually mainly focused on issues connected to the Slovak gas transit,” state Slovak analysts Matus Misik and Andrej Norsko.

“Given the likelihood of a future flat gas demand curve in Europe, combined with the possibility of importing gas as LNG or from western Europe, we consider maintaining transit rent of a semi-private company and perceived energy security represent an insufficient reason for providing public financial support towards building a major infrastructural project,” their 2017 analysis continues.

However, Eustream expects that maintaining Eastring on the EU’s PCI list should be a “reasonably straightforward” part of a hugely complex project, Lalik says. Eastring is unlikely to go forward without EU funding, he admits.

Eustream will then move on to preparing project documentation in 2019, which is expected to take another two years. “It’s a 1,000-km plus pipeline across four countries. It will take years,” Lalik points out.

The Slovak TSO hopes that with the feasibility study under its belt, it can start to make real progress. The positive analyses “move us closer toward investment decisions,” general director Rastislav Nukovic stated in September.

However, Eastring’s prospects remain up in the air, which is hardly an unusual story for pipelines eyeing the southeastern corner of Europe. The SGC has seen numerous contenders fall by the wayside: As well as South Steam, the EU’s Nabucco, Ukraine’s White Stream, Agri (the Azerbaijan–Georgia–Romania interconnector) and Tesla (Greece-Macedonia-Serbia-Hungary-Austria) have all but disappeared from view.

“Even though Eastring is a PCI project, that does not mean it will proceed,” Jirusek asserts. “I wouldn’t bet it will happen any time soon. I don’t think there’s an urgent need for Eastring. TurkStream [gas] can use existing infrastructure or go via TAP.

“What we could see is a limited version that would consist of an interconnector to Romania, rather than running all the way to the Turkish border,” the analyst adds.