Shipping futures: is LNG the fuel of choice? [LNG Condensed]

Following on from a study published in April on LNG’s potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) from shipping, industry group SEA LNG have delved into the economic case for the fuel’s adoption. The study, LNG as a marine fuel – the opportunity for investment, tests LNG-powered vessels against conventional ships and those fitted with open-loop scrubbers, assessing a range of potential fuel price scenarios as implementation of the IMO’s 0.5% sulphur cap looms from January 1 next year.

Scrubber timing

The study argues that time has pretty much run out for ship owners hoping to fit scrubbers. These strip sulphur from a vessel’s fuel emissions, allowing them to continue to burn high sulphur fuel oil (HSFO). According to the study, scrubbers ordered now will not be operational until mid-2020, owing to the backlog of orders and lack of shipyard capacity.

When a scrubber is operational has significant bearing on the investment case because of the likely impact of the IMO sulphur regulation on HSFO prices.

Desulphurisation capacity in the global refining industry is widely regarded as insufficient to cope with the expected increase in demand for fuel oil with less than 0.5% sulphur by mass. HSFO prices are thus expected to fall sharply on or before first-half 2020, as ships switch to lower sulphur fuels, before gradually rising back to more normal levels.

This adjustment will take place as a result of continued scrubber installations, raising demand for HSFO from its lowered base, and refining sector investment in desulphurisation and other means of converting HSFO into more usable and valuable oil products, reducing the product’s availability.

The price plunge and then readjustment mean that recovering the investment cost of a scrubber is likely to take progressively longer the later the installation takes place.

According to shipping consultants Clarksons, as of February, only 4% of the world fleet by number and 10% by tonnage had scrubbers installed or were waiting to have them installed. The figures are for vessels of over 2,000 metric tons gross.

Scrubber woes

Closure of the opportunity window for scrubbers, formally known as exhaust gas cleaning systems, is not the only headwind they face. Open-loop scrubbers discharge the pollutants captured from the engine exhaust into the sea, leading to concerns that they simply transfer air pollution into the water.

China, Singapore and the port of Fujairah in the UAE have all banned the use of open-loop scrubbers in their territorial waters from the start of next year. Individual ports in Finland, Lithuania, Ireland and Russia are also reported to have introduced bans.

Moreover, Lloyds List on September 12, citing corrosion experts, reported that there had been a significant increase in corroded pipework repairs relating to the acceleration in scrubber installations ahead of the IMO regulation implementation, resulting in additional downtime and costs.

The article also cited shipowner DFDS as saying it has experienced virtually no downtime as a result of its scrubbers and comments from other observers that the issue had become highly politicised.

Nonetheless, disenchantment with open-loop scrubbers suggests a shift to closed-loop systems which have higher capital investment and operational costs, or to other alternatives such as LNG.

The SEA LNG-commissioned study also says the operational costs of open-loop scrubbers have been underestimated, but nevertheless assumes a fairly conservative 1% parasitic fuel penalty for their operation.

Emissions debate

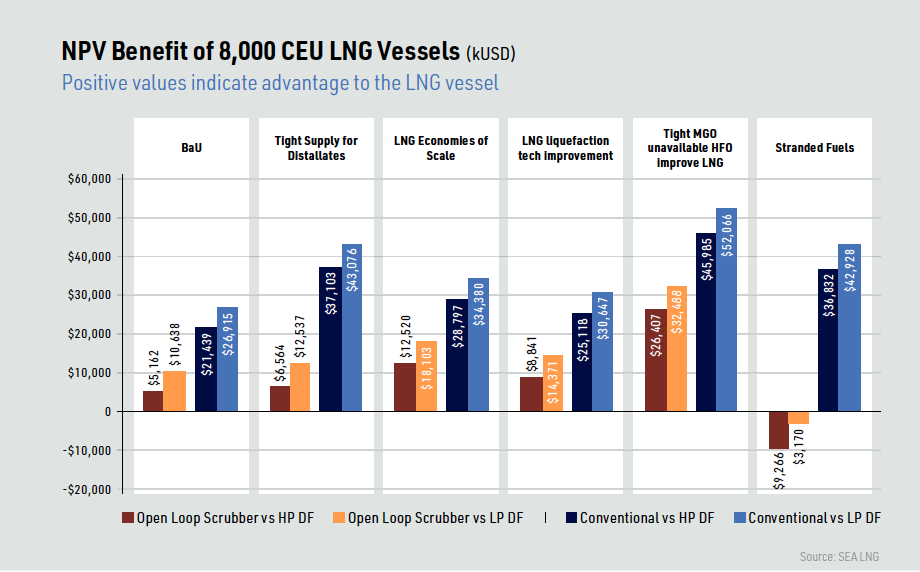

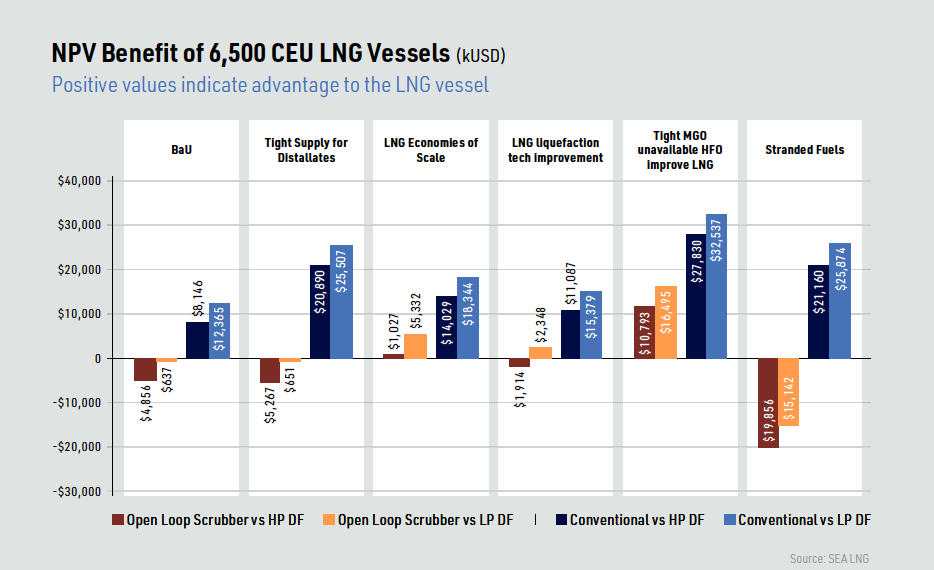

The SEA LNG study examined two trading routes for pure car truck carriers (PCTC), using a 6,500 car equivalent (CEU) vessel for Atlantic trade and an 8,000 CEU vessel for the Pacific. Its conclusion was that LNG as a marine fuel delivers the best return on a net present value basis over 10 years, with fast pay back periods of below three years, although not in all scenarios.

The investment returns were calculated without ascribing a value to LNG’s GHG benefits, an area in which different studies have produced different results. Broadly speaking those studies see LNG as delivering air pollution benefits, owing to reduced nitrogen oxide, sulphur oxide and particulates emissions, but they provide a more nuanced picture when it comes to lifecycle GHGs.

According to LNG Condensed’s investigations of various studies, including SEA LNG’s earlier report, Life Cycle GHG Emission Study on the Use of LNG as a Marine Fuel, the situation is that LNG as a shipping fuel can but does not necessarily generate GHG emissions savings and does not do so to the extent required to meet long-term IMO GHG targets.

LNG appears to be the best short-term option to achieve meaningful decarbonisation, if best practice is employed, within the shipping sector, while new decarbonisation technologies are developed. The use of RLNG – renewable LNG – even as a small proportion of overall fuel use significantly increases the GHG savings from LNG in shipping.

Newbuild versus retrofit

The SEA LNG study is based on a newbuild LNG dual-fuel vessel and as such only addresses part of the problem faced by ship owners. It acknowledges that LNG retrofit costs are higher and require a young vessel with enough future lifetime to justify the costs.

But this is not the central dilemma presented by IMO 2020 which is what to do with existing fleets. Ship age and future lifetime play a huge role in the decisions ship owners make, and a large part of LNG’s case is its capacity to future proof against regulatory tightening of emissions standards, which has more relevance for newbuild vessels.

Fuel costs

However, the main question SEA LNG’s second study addresses is more prosaic, but no less important: will LNG engines pay?

Any such study has to make assumptions about capital investment costs and operational costs. Operational costs incorporate assumptions about future fuel costs, and the SEA LNG report provides different scenarios to test LNG’s economic performance versus oil products.

Its starting point is that “LNG marine fuel is less price volatile than traditional oil based marine fuels.” This is because the cost of LNG comprises the cost of natural gas (25%), a liquefaction fee and then transportation costs, and can be contracted on a long-term basis, while traditional maritime fuels reflect the volatility of crude oil prices, the report says.

This position is contestable. First, while there has been substantial change in the way in which long-term LNG contracts are priced, the vast majority remain tied to the Brent crude oil price, which means they are also affected by oil price volatility. Second, the emergence of a spot market for LNG, in which it trades as a commodity in its own right, can create additional volatility.

If this is viewed in terms of overall price swings – rather than a strictly technical economic definition of volatility – then spot LNG pricing can be pretty unstable, ranging from below $5/mn Btu this summer to close to $20/mn Btu over winter 2017/18 when Chinese LNG demand shot up ahead of expected increases in supply. This is a substantially bigger high/low price range than for oil over the same period.

In reality, oil indexation cuts both ways. Long-term contracts linked to Brent in winter 2017/18 arguably acted as an anchor to run-away prices in the LNG spot market.

Nonetheless, the growth of LNG supply in recent years -- in particular US LNG, backed by the stability of US natural gas prices -- does create a good case for LNG price stability over the short to medium term. However, this is a function of current market conditions rather than some form of stability inherent to LNG as a commodity.

Scenario planning

The study finds that for 8,000 CEU LNG vessels the net present value benefit is substantial in all scenarios against conventional engines, and in all cases versus scrubbers except for its ‘stranded fuel’ forecast. This assumes a sharp drop in HSFO prices from January 1, 2020 and that ship owners already have scrubbers installed from this point.

For the 6,500 CEU LNG vessel, LNG again wins out against conventional vessels, but open-loop scrubbers are better, although only marginally so, in a minority of scenarios, for example business-as-usual, tight supply for distillates, stranded fuels and for an open-loop scrubber versus a two-stroke HP dual-fuel LNG engine in a scenario which assumes gains in LNG liquefaction technology.

The study points out that the lower GHG emissions attributed to LNG in shipping may bring potential financial rewards, for example via some form of carbon pricing, but does not include these in its calculations. In terms of its 10-year investment horizon and operational cost estimates for scrubbers the study is also conservative. It excludes from its calculation any end-of-life vessel value.

However, as with any scenario planning exercise, making the right investment choice depends on which scenario – or one unforeseen – actually comes to pass. This is the big unknowable.

The study’s point that the window for scrubbers to benefit from the stranded fuels scenario has all but passed is a good one. So too is the likely downward trend in LNG engine capex as the market becomes more competitive. Combined with LNG’s regulatory future proofing, this all adds up to a strong investment case, even if a more negative view on LNG versus oil products pricing is assumed.

Ship-building cycle

However, it is still all about newbuilds and the deciding factor here is likely to be the timing of a major new ship-building cycle, which in turn depends on the outlook for global trade.

This has taken a beating this year, owing largely to the US-China trade war. Forecasts for global GDP growth have been revised downward and while container trade continues to grow it is doing so more slowly than in the past.

According to DNV GL, as of May this year, there were 163 LNG vessels in operation and 155 on order. The figures exclude LNG carriers and inland waterway vessels.

Martin Wold, head of the DNV Alternative Fuels Insight platform at DNV GL said that while new LNG ship orders had remained steady at about 40 a year in recent years, that number had been passed in the first five months of 2019, which “could be a sign that the pace for LNG fuel investments is picking up.” He also said installed LNG tank volume will more than triple from around 100,000m3 today by the end of 2020 – i.e. larger ships are adopting LNG.

Even so, it is not the rush to construction that LNG enthusiasts had hoped for. The actual impact of IMO 2020 may change that, but it will also take a recovery in world trade and a new cycle of shipbuilding to really test ship owners’ enthusiasm for LNG as a shipping fuel.

At the same time, given that a large part of the GHG emissions come from the LNG supply chain rather than its direct use as a fuel, there is strong case for cross-industry co-operation between producers, transporters and users of LNG as a fuel to demonstrate that they are indeed employing the best full supply chain practices possible. Some form of financial reward via carbon pricing or ‘clean’ gas certification could both incentivise best practice and, as SEA LNG points out, tip the economic case for LNG adoption further in the fuel’s favour in the future.

The studies commissioned by SEA LNG can be found here:

|

|

You can download the latest issue of LNG Condensed here.