Shell’s transition in focus [Gas in Transition]

Shell presented a new Energy Transition Strategy in mid-April which it will put before shareholders for an advisory vote at the company’s annual general meeting on May 18.

“This is the first time that an energy company has asked shareholders to vote on its energy transition strategy,” the company said in a press release.

The report sets out the company’s “short- and medium-term climate targets, customer-focused decarbonisation strategy, capital allocation and approach to climate-related policy and advocacy.”

Shell notes that the decision to publish this strategy “follows continuing engagement with shareholders, including with Climate Action 100+ which represents investors with assets of around $54 trillion.” The company will publish an update every three years until 2050. Every year, starting in 2022, it will also seek an advisory vote from its shareholders.

Sectoral integration

As one of the world’s largest – if not the largest – supplier of energy, Shell sends quite an important message to the world with its Energy Transition Strategy. The company produces around 1.4% of total primary energy, notes the report, but it sells no less than “around 4.6% of final energy consumed in the world.”

“Our share of energy production may decline over the coming decades, but we intend to grow our share of low-carbon energy sales,” it adds.

Shell intends to “reduce the carbon intensity of our energy products by working with our customers, sector by sector, to help them navigate the energy transition. We will start by adding more low-carbon products, such as biofuels and electricity, to the mix of energy products we sell. Eventually, low-carbon products will replace the higher carbon products that we sell today.”

One of the key elements of the new strategy is a focus on sectoral integration. Shell “is moving from an approach focused on types of products to one where our customer and account management is focused on sectors.” The company is “introducing sector-based businesses accountable for driving the decarbonisation of the sectors they cover such as aviation, commercial road transport, passenger transport, shipping, technology and industry.”

The report cites the road freight sector as an example, in which Shell is “working with transport companies, truck manufacturers and policymakers to identify pathways to decarbonisation. In the near term, we will continue to increase production of low-carbon biofuels. And we will offer biogas and LNG for trucks to customers in Europe, China and the US. In the longer term, we intend to increase our sales of hydrogen for transport. We are also part of the H2Accelerate consortium, which looks at ways to create infrastructure for generating and supplying clean hydrogen to hydrogen trucks as they become available across Europe.”

In step with society

For Shell it is clear that the company needs to move in step with the transition taking place in the larger society. “If we moved too far ahead of society, it is likely that we would be making products that our customers are unable or unwilling to buy,” says the Strategy report. “(…) Shell cannot get to net zero without society also being net zero.”

For example, says Shell, “if we invested in producing sustainable aviation fuel, and made it available on commercial terms at all the airports Shell serves today, the investment would not significantly lower our or society’s carbon emissions. Most aircraft are not yet certified to fly on 100% sustainable aviation fuel and the cost of the fuel is considerably more than traditional jet fuel, making it an uncompetitive choice for the airlines.”

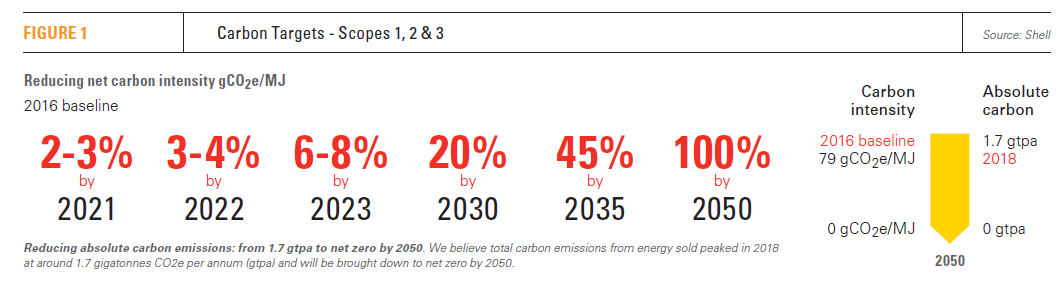

Shell has adopted an emission reduction target of 20% by 2030, reaching 45% by 2035, and 100% by 2050 (see chart). These include Scope 3 emissions, meaning emissions from the use of energy sold by Shell – i.e. not just the company’s own operational emissions.

In absolute terms, this translates into a 340mn metric ton/year reduction by 2030, 765mn mt/yr by in 2035 and 1.7bn mt/yr in 2050. Global greenhouse gas emissions are around 52bn mt/yr, so Shell’s contribution is around 3.25%.

Levers of decarbonisation

So how does this translate into concrete activities? In addition to pursuing “operational efficiency” in its own assets, Shell has five “levers” to help the company and its customers “decarbonise energy in the short, medium and long term”.

More natural gas

Shell notes that its oil production peaked in 2019 and is expected to decline 1-2%/year. The company anticipates “no new frontier exploration entries after 2025”. It will reduce the number of refineries from 13 sites today to six “high-value chemicals and energy parks”, and “reduce production of traditional fuels by 55% by 2030, from around 100mn mt/yr to 45mn mt/yr.”

At the same time, Shell intends “to grow volumes from our chemicals portfolio and increase cash generation from chemicals by $1-2bn/yr by 2030.” It will “produce chemicals from recycled waste, and by 2025 aim to process 1mn mt/yr of plastic waste.”

Shell sees the share of natural gas in its hydrocarbon production grow to 55% in 2030. “We intend to extend our leadership in LNG volumes and markets, with selective investments in competitive LNG assets to deliver more than 7mn mt/yr of new capacity on-stream by the middle of the decade,” says the report. “We will continue to support customers with their own net-zero ambitions, with offers such as carbon-neutral LNG, which uses nature-based carbon credits to offset full life-cycle emissions, including methane.” Shell’s LNG production in 2020 was 33.2mn mt, a decline of 2.2mn mt compared to 2019.CCS

CCS is an important part of Shell’s transition strategy. Today, Shell is involved in seven of the 51 large-scale CCS projects listed in 2019 by the Global CCS Institute, including for example the Quest CCS project in Canada and the Northern Lights project in Norway.

In 2020, Shell invested around $70mn in CCS. “This included progressing opportunities and operating costs for CCS assets in which Shell has an interest. We seek to have access to 25mn mt/yr of CCS capacity by 2035 – equal to 25 CCS facilities the size of our Quest project, or around 20% of the capacity of all CCS projects being studied around the world today.”

Natural sinks

“Investing in nature” is another pillar of Shell’s strategy. “The market for nature-based solutions and the number and type of projects which are being developed to meet this market demand is growing rapidly,” notes the company. “McKinsey Nature Analytics estimates that there is the potential for nature-based projects to store an additional 6.7 Gt [6.7bn mt] of CO2 every year by 2030. …. The Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets (TSVCM), sponsored by the Institute of International Finance (IIF), estimates that the market for carbon credits could be worth more than $50bn in 2030.”

Shell vows to use “high-quality nature-based solutions, independently verified to determine their carbon impact and their social and biodiversity benefits. In line with our approach of avoid, reduce and only then mitigate, we expect to offer our customers nature-based solutions to offset around 120mn mt/yr of our Scope 3 emissions by 2030.”

Shell is already offering its customers “carbon-neutral driving using nature-based carbon offsets in seven countries. We also offer carbon-neutral LNG cargoes, which use nature-based carbon credits to offset full life-cycle emissions, including methane.”

In 2020, Shell invested around $90mn in the future development and purchase of nature-based offsets, and the company expects to invest an additional $100mn/yr in similar projects. In 2020, it acquired Select Carbon in Australia, “which runs more than 70 carbon farming projects that span an area of around 10mn hectares.”

Low-carbon fuels

Shell expects to grow its biofuels production and distribution business, which in 2020 sold 9.5bn litres of biofuels. Its joint venture Raízen, which produces low-carbon biofuels from sugar cane in Brazil, recently announced the acquisition of Biosev. This is set to increase Raizen’s bioethanol production capacity by 50%, to 3.75bn litres/yr, around 3% of global production.

With regard to hydrogen, Shell intends to develop “integrated hydrogen hubs initially to serve industry and heavy-duty transport. We will begin by producing and supplying hydrogen for our own manufacturing sites, especially refineries. … We will also continue to extend our network of hydrogen retail stations, with an increasing focus on heavy-duty transport.”

The clean hydrogen market is still in the early stages, notes Shell, and the volumes are still modest. “But we see strong potential for growth especially in hard-to-abate sectors of the economy. We aim to achieve a double-digit market share of global clean hydrogen sales by 2030.”

Low-carbon power

Shell aims for its power business “to sell around 560 TWh/yr of electricity by 2030, which is twice as much electricity as we sell today, and for the electricity we sell to have lower carbon intensity than the grid average within the markets where we operate.”

The company is also increasing “the number of electric vehicle charging points globally – for homeowners and businesses and for use on our forecourts – from more than 60,000 today to more than 500,000 by 2025 and to 2.5mn by 2030. By comparison, that is around 7% of the total number of public and private charge points expected in Europe alone by 2030, according to research by Bloomberg.”

Shell currently has around 1mn customers of integrated home energy solutions (Shell Energy Retail), more than 80,000 operated electric vehicle charge points (primarily through NewMotion), 60,000 intelligent home battery energy storage systems (Sonnen). Shell is also “a leading player in the UK distributed energy market” (Limejump) and has a “growing power trading business across Europe”.

It has 160 MW of renewable generation capacity in operation (in the Netherlands) and 1.6 GW in development across solar and wind.

Capital allocation

Shell’s strategic shift will of course have an impact on the way it spends its money. The Energy Transition Strategy looks at this from the bright side. It notes that “compared with our conventional upstream assets, investments in low- and zero-carbon solutions can require lower amounts of capital…. The levels of capital investment needed to maintain a renewable energy business are also likely to be lower than in capital-intensive complex engineering projects common in the oil and gas industry.”

What is more, Shell notes that “we can grow our sales of low-carbon energy without necessarily investing in producing it ourselves by buying it from third parties and selling it to our customers. This model is part of our business today, we sell more than three times the energy we produce ourselves.”

Shell also sees an opportunity to “enter into different types of financial arrangements that enable renewable generation capacity to be built, without bearing the full capital cost of the project. For example, developing renewable production as part of joint ventures allows us to reduce the capital investment needed, while giving us access to valuable expertise from other partners. It also gives us the opportunity to secure a substantial portion of the energy produced, allowing us to grow customer sales.”

By contrast, the company’s investment in the upstream, in particular the oil business, will gradually be reduced. “Our planned capital investment of $8bn in our upstream business in the near term is well below the investment level required to offset the natural decline in production of our oil and gas reservoirs, and will not sustain current levels of production. As a result of this planned level of capital investment, we expect a gradual decline of about 1-2%/yr in total oil production through to 2030, including divestments.”