[NGW Magazine] SE Europe: Linking Supply to Demand

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 20

By Charles Ellinas

There are many unknowns in the Southern Corridor Region such as Black Sea production and overall demand; even if not all the projects vying for funding are built, the choice of supplier will be wider than now.

The European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (Entsog) sees progress in a number of major projects that will enhance the role of the Southern Corridor region (SC), comprising the EU countries in southeast Europe (SEE) in its new study.

Released September 19, it is the third edition of the SC Gas Regional Investment Plan (Grip 2017) covering the ten-year reference period 2017 to 2026.

It was prepared by SC’s transmission system operators (TSO) under the co-ordination of Greek TSO Desfa. It builds on Entsog’s Ten-Year Network Development Plan, TYNDP 2017-2026, published in December 2016.

Grip 2017 aims to shape the SC region energy landscape in the coming decade. The nine EU countries it covers are: Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

Natural gas supply

Indigenous natural gas production plays an important role in some SC countries, particularly in Romania where it is expected to cover 79% of annual demand in 2017, rising to 100% by 2026.

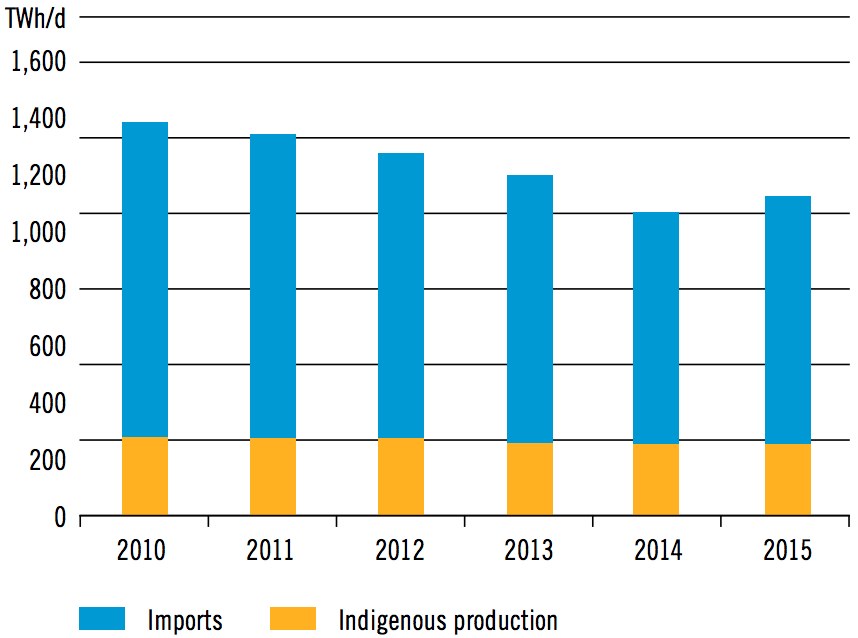

Over the five years to 2015 indigenous gas production in the SC region was more or less stable. Its share was 22% of the overall demand in the SC region in 2015 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Gas imports and indigenous production in the SC region

Grip 2017

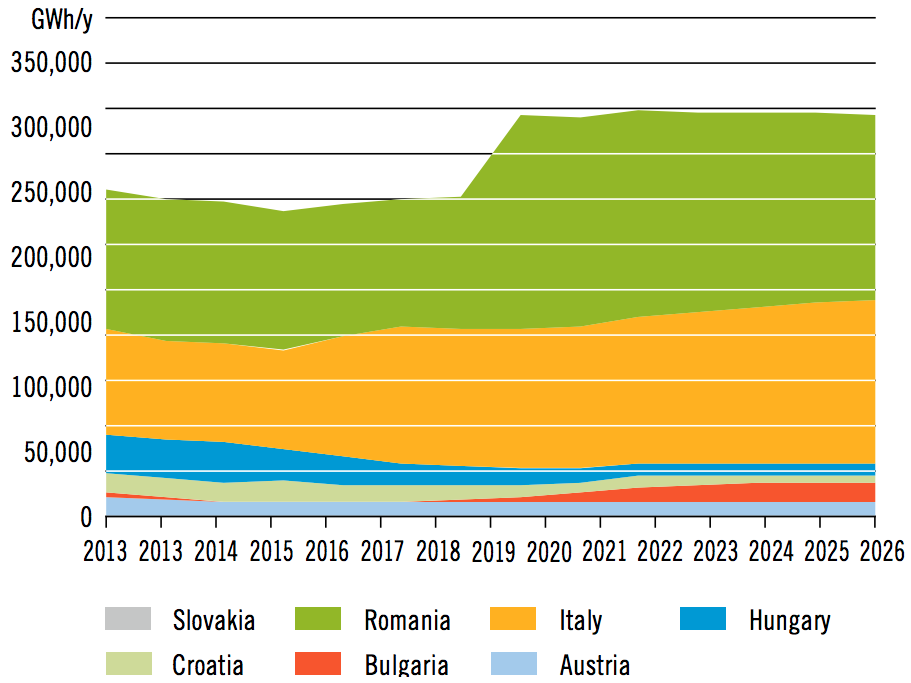

Forecast national gas production of countries in the SC region over the reference period is shown in Figure 2. Romania expects to bring newly discovered gas-fields in the Black Sea onstream by 2020, becoming the major gas producer in the region.

Figure 2: Forecast national gas production

Grip 2017

Grip 2017 also considered gas imports from Cyprus, especially through the eastern Mediterranean gas pipeline. The feasibility study for this was funded by the European Commission as a ‘project of common interest’.

However, this depends on the potential amount of gas, still to be discovered, and the commercial feasibility of the pipeline. Low gas prices in Europe make it a challenge.

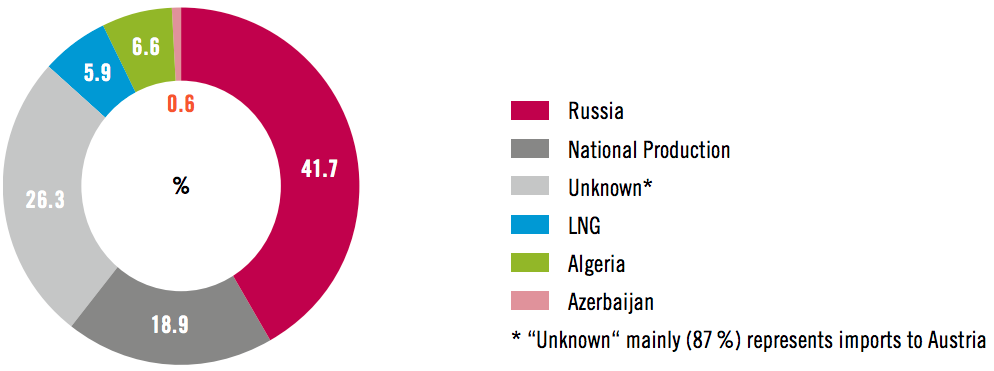

Gas imports to the SC region were well diversified in 2015, with only 41.7% coming from Russia (Figure 3). However, in Bulgaria, Croatia and Hungary, Russian gas accounted for more than four fifths of the supply.

Figure 3: Diversification of 2015 gas imports to the SC region

Grip 2017

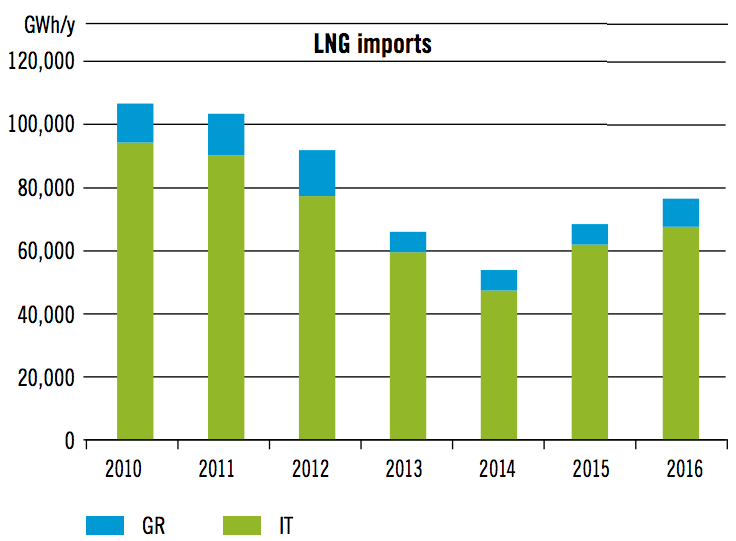

LNG imports by Italy and Greece, having declined in the period 2010 to 2014, have been seeing a resurgence since then driven by low prices (Figure 4). Grip 2017 notes that much will depend on what LNG prices do in the coming years and new LNG import terminals, but it expects that LNG may increase its share of the region’s imports from its 6% in 2015.

Figure 4: Evolution of LNG imports by Italy and Greece

Grip 2017

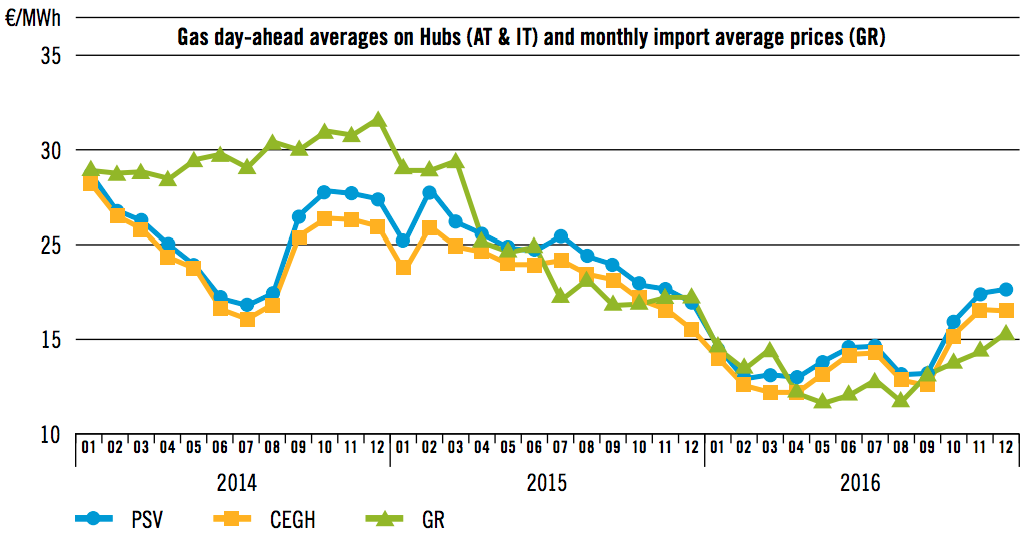

Gas import prices in the SC region converged during the last two years (Figure 5), but remain slightly higher than those of the markets of central and western Europe. The difference between Greek, Austrian (CEGH) and Italian (Punto di Scambio Virtuale) hub prices is due to oil indexation.

Figure 5: Comparison of gas prices in the SC region

Grip 2017

Not surprisingly, Austrian and Italian hub prices are more closely aligned by virtue of their linkage to the major European hubs: the Dutch Title Transfer Facility and British National Balancing Point.

However, Italian gas prices are consistently higher than Austrian gas prices, on average by more than €1/MWh, reflecting the north-south flow of gas. This is one of the reasons Italy is pursuing direct gas imports through a southern route.

Natural gas demand

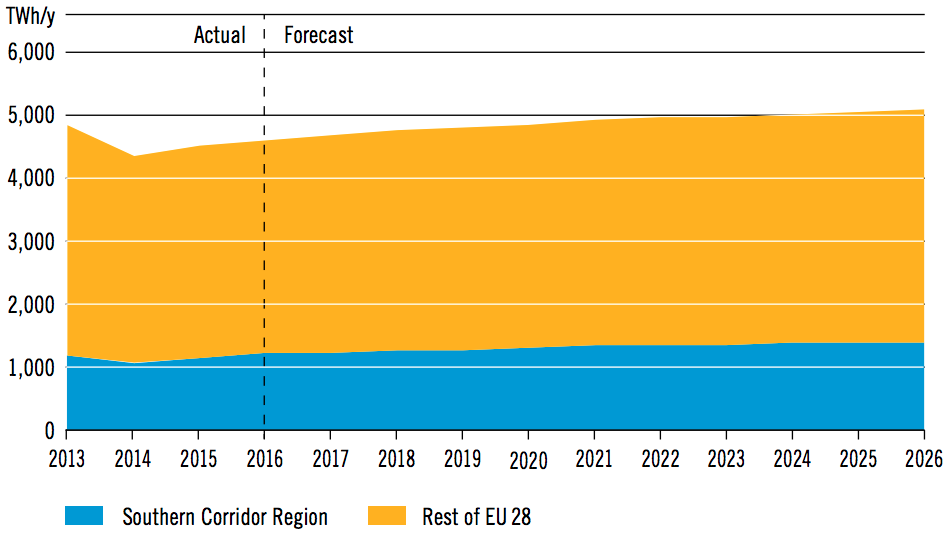

The SC region is responsible for a quarter of European gas demand, which is projected to grow to 27% over the next decade as SC markets grow and gas penetration continues (Figure 6). Italy remains the largest gas market in the SC region, representing 63% of the total demand. However, an examination of annual demand trends over the last seven years is revealing.

Figure 6: SC annual gas demand versus EU-28

Grip 2017

The downward trend that prevailed 2010-14 is partly due to economic contraction but also to the low prices of coal and of carbon emissions under the EU emission trading scheme, which has perversely squeezed out gas.

In addition, over the same period, increased uptake in renewables reduced total demand for gas in electricity generation. In other words, gas was squeezed between cheap coal and subsidised renewables.

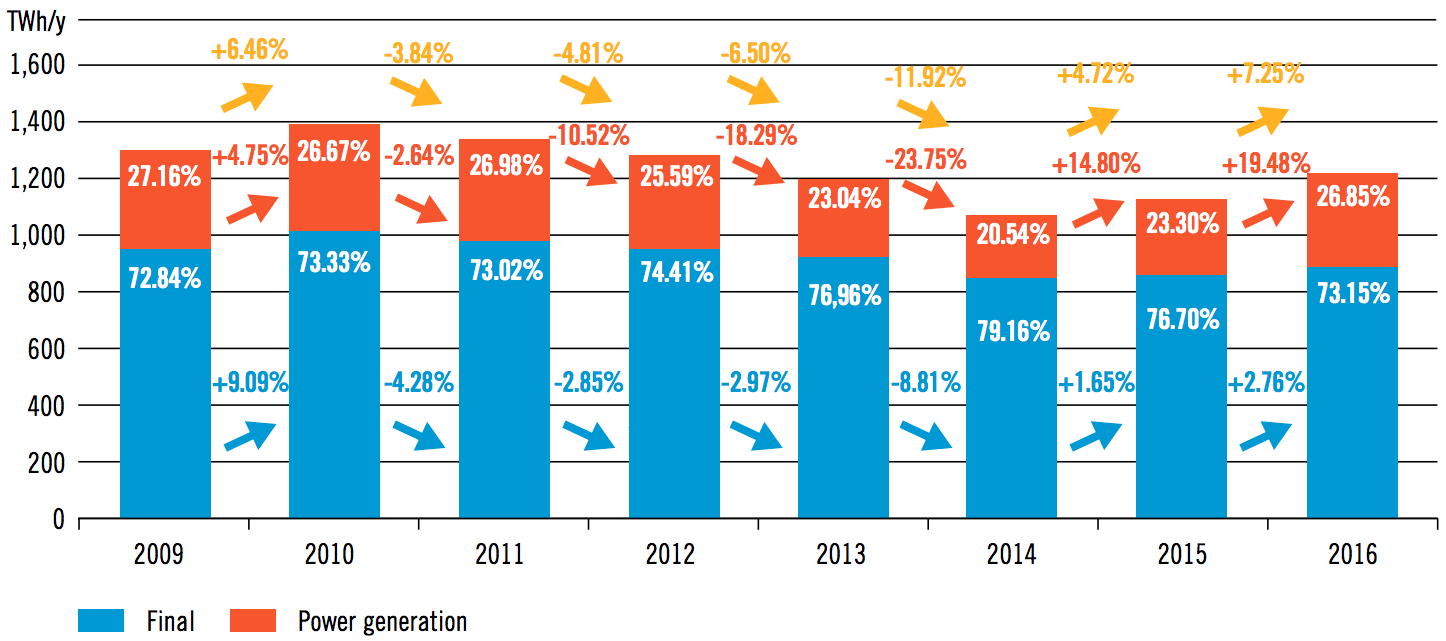

Figure 7: Changing SC annual demand

Grip 2017

However, this downward trend was reversed in the period between 2015 to 2017 thanks to the reduction in the oil price, which led to cheaper gas through oil indexation.

Evidently, fuel price matters despite pressure from the Paris Climate Agreement and EU to reduce emissions. Even in the SC region, like elsewhere in the world, the ups and downs in the use of natural gas are largely dictated by prices.

However, SC gas demand may increase further in future due to phasing-out of nuclear plants in some countries and increasing pressure to reduce pollution from coal plants.

Impact of renewables

The use of renewables, including hydro, and gas in power generation in SC countries in 2015 is summarised in Table 1.

It is evident that there is great variability both in the use of renewables and gas. Grip 2017 states that there are no available annual data about planned installation and use of renewable sources in primary energy production over the next ten years in any of the countries of the SC region.

However, those countries which provided data did show rising use of renewables.

For example, in Greece the share of renewables in power generation is expected to reach 32% by 2027, compared with 11% last year.

Italy is planning the complete phase-out of coal by 2030, enshrined in its National Energy Strategy, to be replaced by gas and renewables.

The most significant developments expected to impact future use of renewables and energy efficiency in the SC region will be driven by the need to comply with European energy and climate energy objectives, and by the adoption of a challenging long-term EU strategy with progressively ambitious objectives.

Key projects

Grip 2017 contains details of all transmission and interconnection projects in the SC region presented by country. Out of a total of 131 projects:

- 65 were present in Grip 2014–2023

- 8 have been successfully commissioned

- 44 are new projects

- 14 have been withdrawn

Out of these, 20 are at FID stage.

The resilience of SC’s gas transmission and interconnection network was examined through modelling expected gas flows through three sources: Russian gas, LNG and Azeri gas.

Particular reference is made in Grip 2017 to the importance of the TransAnatolian and TransAdriatic pipelines (Tanap and TAP), IAP, EastMed, Interconnector Greece-Italy Poseidon (IGTI), Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (IGB) and Eastring.

Grip 2017 notes that despite progress with TAP, there are still uncertainties in realising several initiatives, such as the North-South and East-West interconnections. At a meeting in early September, the energy ministers of Bulgaria and Greece called on the EU to allocate more funds for the Vertical Gas Corridor. This comprises the LNG import terminal at Alexandroupolis, IGB and the Bulgaria-Serbia interconnector.

In the case of IGI Poseidon, Grip 2017 states that the cancellation of the South Stream pipeline may be a good reason to keep this plan alive. Its main objective is to complete the natural gas corridor through Turkey, Greece and Italy.

The report acknowledges that in February 2016 ‘the shareholders of IGI Poseidon, respectively [Greek importer] Depa with 50% and [EDF-owned] Edison with 50%, signed with Gazprom a Memorandum of Understanding in relation to gas supplies from Russia across the Black sea through third countries to Greece and from Greece to Italy to develop a gas pipeline project between Greece and Italy, enabling the realization of a new route for gas supply’.

This was followed up by a further agreement between the three parties in St Petersburg in June 2017. With Turkey ratifying the IGTI pipeline early October, it opens up possibilities for Russian gas to Europe through this route.

Gazprom is proceeding with plans to complete both strings of TurkStream by 2019 and Hungary has already confirmed plans to buy gas through TurkStream 2, rather than alternatives that could arrive at the planned Krk LNG terminal (see below). Additional supplies of gas through these transmission projects will have a positive effect on security of supply and diversification of routes and sources of gas in SC countries and Europe more generally.

LNG or UGS

LNG import projects in the SC region are intended to contribute to diversification of sources and increase security of supply in case of disruptions of existing and other sources. These include new terminals or expansion of existing terminals.

The Croatian LNG terminal at Krk island represents an additional source of natural gas for Croatia as well as its neighbours such as Hungary, Slovenia, Austria, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Serbia, by providing a new gas supply route for the central and south-eastern European countries (CESEC). LNG terminals in Greece: at Revythousa and Alexandroupolis: the main objective of these projects is to provide an additional source of natural gas for Greece and enable gas to flow to the north to Bulgaria, FYRoM, Serbia, Romania, Hungary and up to Ukraine, through the Vertical Gas Corridor. Porto Empedocle LNG in Italy: Italy’s new national energy strategy 2030 lays out plans to develop an additional LNG terminal. Numerous candidates have been proposed but only three have received full authorisation. Of these, Enel’s 8bn m³/yr facility planned for Porto Empedocle in Sicily is the most likely to be defined as strategic. Medgas LNG is another option.

However as is the case with the rest of Europe, SC LNG import terminals are under-used, wasting money depending how much value is put on security of supply. Underground gas storage projects include facilities in Bulgaria, Romania, Greece and Italy to enable seasonal balance of supply and demand and to make gas supply more reliable.

Security of supply

In terms of supply the SC region faces probably the biggest challenges across Europe. However, should they materialise, new potential sources of gas, such as the Caspian, eastern Mediterranean, Middle East and new routes are expected to have a positive impact on the region, but also Europe. Additional potential may be provided by the TurkStream pipeline, of which two lines are now being built from Russia directly to Turkey.

In addition, the new LNG terminals, in the Adriatic and in northern Greece are key projects that can contribute to the improvement of network flexibility and security of supplies.

Under normal, non-disruption, conditions, Grip 2017 states that demand and supply of the SC region are well balanced. However, the region is still vulnerable to the disruption of the Ukrainian route. New projects, including completion of PCIs, will help satisfy part of the expected demand but are not sufficient to fully mitigate the situation. As a result, some of the new projects, such as those that are aiming at the transmission of gas through Turkey from various sources, are needed to ensure a complete redress.

However, even then Romania remains exposed, but this could be drastically changed once the new gas-fields in the Black Sea are put in operation.

This again proves that the region has high dependence on Russian gas, although this is expected to be reduced for some of the countries once the PCIs are built. These findings support European commission’s view that the EU is well on its way to a resilient gas system, up to 2025, that can respond to any supply shocks. On this basis, assuming that projects identified in EU’s energy strategy are implemented, no new investments are envisaged.

Charles Ellinas