Sanctions one of many pieces in Iranian LNG jigsaw [Gas In Transition]

Western dependence on Russian oil and gas has never faced such intense scrutiny. Amid a raft of sanctions, the US has called an immediate halt to Russian hydrocarbon imports. The UK has pledged to follow suit by the end of the year. The EU is in a more difficult position, as it depends on Russia for about 40% of its gas needs. However, the German government, in particular, now appears to have abandoned hope that energy sector engagement can help restrain the worst of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s foreign policy excesses.

The crisis has prompted Western leaders to seek improved relations with other important oil and gas suppliers. UK prime minister Boris Johnson has tried to smooth over his country’s strained relations with Riyadh, while Qatar finds itself with a long list of suitors. US diplomats have tested the water to see if the governments of Venezuela and Iran would be open to agreements that could pave the way for the lifting of sanctions on both countries.

.png) Iranian potential

Iranian potential

Iran has the second biggest gas reserves in the world (see figure 1), but accounts for less than 1% of international trade in gas through its piped exports to Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Iraq (see figure 2). Its ambitions to develop LNG plants have long been hampered by international sanctions, but potentially it could host an LNG industry on a par with the world’s largest producers.

Tehran has made a lot of noise about not needing Western support to develop LNG plants, arguing that it can either go it alone or rely on other foreign backers. The National Iranian Gas Export Company and other Iranian state owned investors began developing the first of four planned 5.4mn mt/yr LNG trains in the Pars Special Economic Zone in 2007, but the anticipated sale of a 40% stake to a foreign partner never emerged and the project was never completed.

This suggests that Tehran does need Western investors, developers and technology, as well as market support to bring LNG projects on stream.

Nuclear deal resurrected?

Tehran has always insisted that its nuclear programme has purely civilian rather than military goals, but international monitors and Western governments disagree. Under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed by Iran, the US, the UK, France, Germany, Russia, China and the EU in 2015, Iran was to dispose of its stocks of enriched uranium and massively reduce its enrichment and heavy water production capabilities in return for the suspension of sanctions.

However, the US pulled out of the agreement because former US president Donald Trump wanted a permanent ban on Iranian uranium enrichment and a ban on Iran developing ballistic missiles capable of deploying nuclear weapons. In addition, Trump wanted the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to be given access to Iranian military sites.

Iran said it would resume its nuclear programme as a result of the US withdrawal and the IAEA reported this March that the country had exceeded limits on its stock of enriched uranium.

US president Joe Biden promised to breathe new life into the agreement when he came to power in January 2021 and talks have been held in Vienna over the past eleven months.

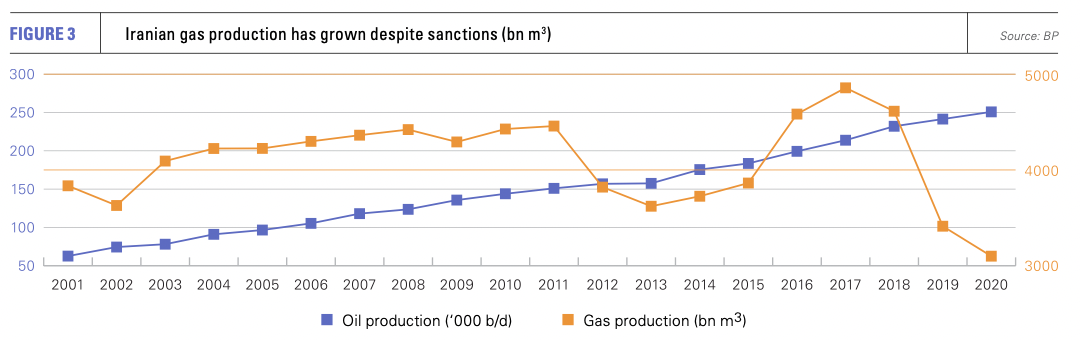

Official Iranian media outlets have greatly talked up Iran’s gas potential in recent months (see figure 3), suggesting that the government is keen to reach an agreement. However, a number of stumbling blocks remain, including the US refusal to lift its designation of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps as a foreign terrorist organisation.

Washington’s position is key, given that it was the US that originally pulled out of the JCPOA. Its sanctions on Iran not only apply to US investment in Iran, but also block access to the US financial system for Iranian companies and, crucially, levy penalties on non-US firms that do business with Iran via their US operations.

Not just about sanctions

Even if a new nuclear deal is agreed, there are a number of reasons why investors should remain cautious.

First, it is possible that the war in Ukraine and sanctions against Russia may actually make a renewed JCPOA less rather than more likely. Russia was one of the original signatories of the JCPOA and would be required to sign a revived deal. It has demanded that its trade with Iran be protected from US sanctions under any new agreement. In addition, it had been expected that Russia would import Iran’s stockpile of excess enriched uranium and provide fuel for Iran’s Bushehr power plant.

First, it is possible that the war in Ukraine and sanctions against Russia may actually make a renewed JCPOA less rather than more likely. Russia was one of the original signatories of the JCPOA and would be required to sign a revived deal. It has demanded that its trade with Iran be protected from US sanctions under any new agreement. In addition, it had been expected that Russia would import Iran’s stockpile of excess enriched uranium and provide fuel for Iran’s Bushehr power plant.

It appears unclear whether Moscow would veto a new agreement, which could be signed in a different form, providing that the US, Iran and probably China agree. It is also possible that other countries could take over Russia’s commitments under the original JCPOA, if necessary.

Second, LNG plant development involves long-term investment certainty. In the past 20 years, Iran’s relations with the West have been volatile. Any developer would have to be confident that their investment will not be stranded by future swings in political relations.

The current suspension of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project is a case in point. Another, perhaps more relevant example, is the Iran-Pakistan pipeline, where work on the Pakistani side has been held up by US sanctions for many years. At no point over the last two decades has any major potential investor been sufficiently confident to make a final investment decision in Iranian LNG.

Third, Iranian opposition to and restrictions on foreign investment in the country’s oil and gas industry remain. While some within the country’s political establishment have welcomed Western involvement in developing their economy, opponents have generally held sway. Even when European and North American governments have looked favourably upon investment in Iran, the investment regime has included too many restrictive elements, including requirements to work through Iranian partners and limits on profits.

Third, Iranian opposition to and restrictions on foreign investment in the country’s oil and gas industry remain. While some within the country’s political establishment have welcomed Western involvement in developing their economy, opponents have generally held sway. Even when European and North American governments have looked favourably upon investment in Iran, the investment regime has included too many restrictive elements, including requirements to work through Iranian partners and limits on profits.

Political uncertainties

Uncertainties abound in all areas. Even if Tehran were to put pen to paper on a nuclear deal now, important elements in the government appear determined to secure nuclear weapons. There is little doubt that joining the nuclear club would give Iran huge bargaining power in relation to its biggest enemies, including the US itself, Israel and Saudi Arabia. Reports over exactly how much progress its nuclear programme has made vary greatly, but it seems reasonable to assume that it has advanced its technological aims in the four years since the US pulled out of the 2015 agreement.

If nuclear detente is reliant on Biden’s position as president, then it would help if he stayed in post for two terms, or another president interested in reviving the deal was elected. At present, Biden’s opinion polls indicate falling popularity amid economic problems and continued Covid deaths, but it is still too far out from the next election to guess at his chances of winning a second term.

.png) Moreover, as Washington’s eagerness to strike a deal with Tehran is based on its even greater keenness to cut ties with Putin’s Russia, much depends on Russian domestic developments. Barring an unlikely change of stance on Putin’s part, sanctions will probably stay in place until he is removed from power. There is every possibility that he could be overthrown by those within Russia. If a new government were installed in Moscow, Russian oil and gas could begin flowing to the West once again, particularly as the infrastructure to support the trade is already in place.

Moreover, as Washington’s eagerness to strike a deal with Tehran is based on its even greater keenness to cut ties with Putin’s Russia, much depends on Russian domestic developments. Barring an unlikely change of stance on Putin’s part, sanctions will probably stay in place until he is removed from power. There is every possibility that he could be overthrown by those within Russia. If a new government were installed in Moscow, Russian oil and gas could begin flowing to the West once again, particularly as the infrastructure to support the trade is already in place.

The prospect of a new nuclear deal between the West and Iran seemed more likely as soon as Biden was elected and Trump departed. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has injected more urgency into the talks. However, the fact is that many more pieces of the jigsaw must fall into place before Iranian LNG becomes a realistic proposition.