Russia’s views on energy and territory [NGW Magazine]

The Russian government approved its Energy Strategy to 2035 (ES-2035) in April. A month earlier, the president, Vladimir Putin signed off the ‘Basic Principles of Russian Federation State Policy in the Arctic to 2035’ (BPA-2035) defining how Russia’s state policy in the Arctic zone will be implemented.

In May 2019, Putin approved a new energy security doctrine which includes “strengthening co-operation with foreign partners, defending Russian energy companies' legal rights abroad and access to international markets, and further developing Russia's import replacement program.”

The doctrine reflects changes in the “Russian government's energy priorities in the wake of the introduction of Western sanctions against Russia since 2014, and successful co-operation on managing oil market volatility with Opec since 2017.”

ES-2035 identifies a number of key goals:

- Sustaining Russia’s position in global energy markets;

- Diversifying energy exports towards Asian markets;

- Ensuring energy availability and affordability for domestic consumers;

- Reducing energy intensity and emissions;

- Developing renewable energy systems.

ES-2035 specifies production, consumption and export targets to be achieved for all forms of energy at two specific milestones: 2024 and 2035. It assumes average annual GDP growth of 2%-3%.

Taking 2018 as the reference year, the key priorities and conservative and optimistic forecasts identified in ES-2035 are:

- Primary energy resource production rises 4.8%-7.4% by 2024 and by 8.6%-21.2% the end of the period.

- Energy demand goes up 6%-10.4%.

- Power demand rises 30%-35%, up to 1370-142 TWh/yr.

- Energy exports to rise 10.7%-13.9% by 2024 and 16.1%- 32.4%.

- The primary fuel mix to change so that:

- Ø Natural gas rises from 41% in 2018 to 46%-47%;

- Ø Crude oil declines from 39% in 2018 to 31%-32%;

- Ø Coal rises from 13% in 2018 to 14%-16%;

- Ø Non-fossil fuels, mostly hydro and nuclear, to remain stable at less than 8%.

The fact that energy exports are key to Russia’s future is evident from the ambitious export targets. Russia is one of the top energy exporters in the world and it appears to be determined to maintain that position. In 2018 it was the leading gas exporter, runner-up in crude oil and third in coal exports.

A key assumption in ES-2035 is that global energy will be provided predominantly by hydrocarbons.

Although ES-2035 is a long-term strategy, it also takes account of the turmoil in energy markets, envisaging further co-operation among the world's energy producers to regulate the market. It talks about "strengthening co-operation with Opec and non-Opec producers and other international co-operation opportunities." This was brought to the fore April 13 with the Opec+ agreement to end the oil price war and cut global oil production by 9.7mn barrels/day. Russia is now firmly embedded into this process, having earlier resisted involvement in cuts from May.

Even though these documents provide general guidelines to the future development of Russia’s energy sectors, a key question is how relevant will they remain in a fast-changing global energy world. Covid-19 is causing major upheavals in global geopolitics, the global economy and global energy, as vividly witnessed during the last two months, that will take years to recover from. Post-Covid-19 the world will be different.

Nevertheless, these documents describe Russia’s energy development path to 2035 and provide a better understanding of the country’s future energy policies.

Impact of energy on Russia’s economy

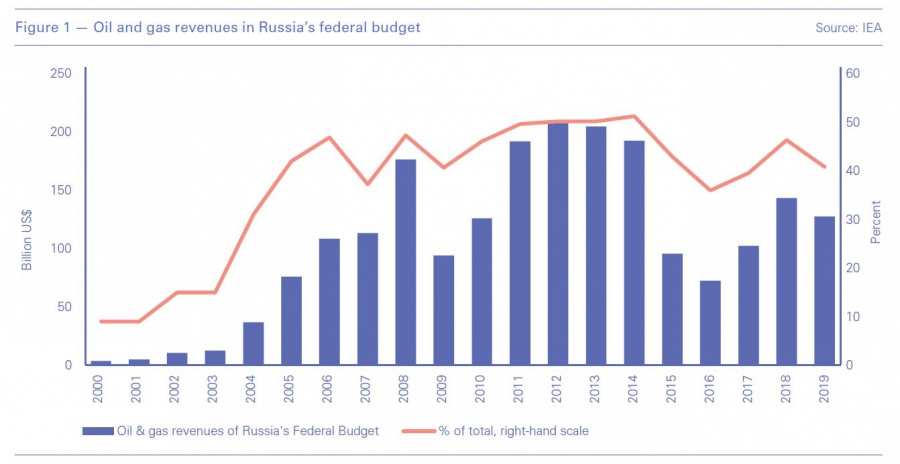

Energy plays a dominant role in Russia’s economy and exports. In 2019 oil and gas were responsible for more than 60% of Russia's exports and provided more than 30% of the country's GDP. Oil and gas revenues also make a major contribution to Russia’s federal budget (Figure 1).

Since the last oil price war in 2014, and as a result of the international sanctions by the US and the EU, Russia was forced to diversify. This led to a drive for self-sufficiency and import substitution, especially with regard to oil and gas technology and equipment, some of which – turbines and some grades of steel for example – can also have military applications.

In order to reduce dependence of the Russian energy sector on imports, emphasis is placed on achieving a significant increase in the share of domestic equipment, goods and services. Adapting to sanctions has therefore stimulated research and development at home, benefiting the Russian economy.

Russia has however had only limited success diversifying its exports from raw materials, with the notable exception of military hardware.

In addition, its sovereign wealth fund holds more than $150bn and its budget is based on a more realistic fiscal break-even oil price of about $42/barrel. In 2018 and 2019 Russia’s government ran a budget surplus, and its total public debt is only about 15% of GDP. These are impressive figures that set Russia on a stronger footing to deal with the ups and downs of the global energy sector.

But nevertheless, Russia is still dependent on oil and gas revenues that make it vulnerable to the developments – and the turmoil - in the global market.

Despite sanctions, Russia remains attractive to many international oil companies (IOCs) because of its huge remaining undeveloped resource base.

Oil

Russia has been successful in growing oil production over the last 20 years from about 6mn b/d in 1999 to more than 11.25mn b/d in 2019. This has helped Russian oil companies Rosneft and Lukoil become serious players in the international oil industry.

However, in the period to 2024 ES-2035 expects oil production to stay within the range 11.15mn b/d to 11.25mn b/d, declining to between 9.84mn b/d and 11.15mn b/d.

Efforts to maintain the country's oil output close to current levels include the transformation of the country's current revenue-based tax system to one based on profits, measures to maximize output from mature fields and the development of hard-to-recover reserves, including oil from shale formations.

It is hoped that the new tax measures will provide greater incentives to invest in new greenfield projects, as well as more expensive enhanced recovery techniques.

Special attention is also paid in ES-2035 to the country's offshore resources and the Arctic onshore region, which are expected to become key to future production. The strategy also envisages the development of home-grown technology by Russian companies, including oil-field services and digital technology – this is well on the way.

Gas and LNG

Russia has been successful in growing its gas production over the last 20 years from about 590bn m³/yr in 1999 to about 790bn m³/yr in 2019.

ES-2035 expects gas production to range between 795bn and 820bn m³/yr by 2024, rising to between 860bn m³ and 1tn m³/yr by 2035.

ES-2035 also has set a goal to increase LNG production to between 46mn and 65mn mt/yr by 2024 and to between 80mn and140mn mt/yr by 2035 from around 30mn mt/yr last year. The wide range reflects the uncertainty around future LNG projects worldwide, but also Russia’s determination to set more ambitious targets for LNG.

ES-2035 places particular importance on gas through:

- Higher potential from the gas-fields in Yamal and eastern Siberia and an optimistic view on the prospects of new LNG projects.

- Rapid development of eastern Siberian and the Russian far east resources for exports to the Asia-Pacific region.

- Implied preservation of Gazprom’s central role in the industry. This is not explicitly mentioned in ES-2035, but neither is the possibility of Gazprom’s unbundling and the separation of the gas transportation network. Gazprom remains the dominant producer.

It recognises that in the near term, gas imports by European countries – Russia’s main energy export market – will rise with the fall in domestic production. But it also recognises that there will be increased diversification of supply sources to Europe. In the longer term there will also be an increase in the share of renewable energy in Europe’s energy balance.

The Asia-Pacific region is the centre of gravity for energy demand growth and ES-2035 sees this as providing new opportunities for Russian energy exports, but building transport infrastructure will be very costly.

Russia is aiming to become a major player in the global LNG market, in the same league as major producers such as Australia, Qatar and US. In order to facilitate this, Russia's parliament, the Duma, passed legal amendments in April allowing more projects and potentially new players to develop liquefaction facilities, as it looks to establish itself as a top-tier LNG exporter.

It sees LNG as an opportunity to diversify its gas exports, which are dominated by pipeline gas supplies to Europe. Part of this diversification includes use the northern sea route to ship LNG cargoes east or west from Novatek’s existing and new Arctic LNG plants.

In addition to the massive increase in LNG production, ES-2035 sets the goal of making Russia a global leader in the production and export of hydrogen to take advantage of the decarbonisation trend in the energy industry, particularly in Europe.

Even though not explicitly stated in ES-2035, Moscow’s support of Novatek’s LNG projects does not impact Gazprom’s monopoly as a pipeline gas exporter.

The new 38bn m³/yr Power of Siberia pipeline taking gas from Russia to China, inaugurated last December, marks a turn by Russia to the east. There are also plans for a second, 50bn m³/yr, pipeline from Russia to northern China – through Mongolia – that Putin announced in March.

Russia is also confident that Nord Stream 2 will be completed. With Turk Stream 2, it completes Gazprom’s strategy to be a major energy supplier in Europe without being dependent on transit through third countries, an idea which it first realised with the Blue Stream line to Turkey.

Apart from global political realignments, sanctions have pushed Russia and China closer together, with closer co-operation in energy, including pipelines and LNG. Another factor is the decline of gas demand in Europe: depending on the success the European Commission has with the Green Deal, the bloc’s gas demand will decline even further, which could accelerate Russia’s pivot to the east.

Renewables and carbon emissions

ES-2035 expects a significant increase in electricity production in Russia over the period, but this will be met mostly by thermal power plants, nuclear and hydro.

The share of renewables, solar and wind, remains negligible. In 2018 solar and wind accounted for 1.4 TWh, or about 0.1% of the total power output. According to ES-2035, the target is to increase this share to between 46-52 TWh by 2035. Although growth appears to be very strong, it will constitute less than 4% of the total power output by then.

ES-2035 also identifies use of energy saving and energy efficiency technologies to limit increase in the total energy demand and to reduce the energy intensity of GDP. There is a huge potential in this, as Russia’s energy intensity exceeds the global average by 1.5 times.

Russia signed the Paris Agreement in 2016 and ratified it in September 2019, with voluntary obligations to limit anthropogenic greenhouse-gas emissions to 70% to 75% of 1990 emissions by 2030, provided that the role of forests is taken into account as much as possible. This is actually a very low target, which is guaranteed.

This is reflected in the Climate Action Tracker report on Russia that states: “It is more than likely that Russia will achieve its Paris Agreement target, a target so weak it would not require a decrease in greenhouse gas emissions from current levels – nor would it require the government to adopt a low-carbon economic development strategy. As a result, we have given Russia a rating of Critically Inefficient.”

However, the Tracker also points out that there is an upward trend in the uptake of renewables and an increasing number of regulations promoting renewable energy deployment. This has been attributed to the benefits of renewable energy sources in Russia, which include contributing to economic growth, diversifying its energy mix, and reducing energy supply costs in remote areas of the country.

Despite this, renewable energy does not have a prominent role in ES-2035.

Plans for the Arctic

BPA-2035 sets out Russia’s policy plans to develop the energy-rich Arctic region. It includes incentives to accelerate economic development, boost investment in energy projects and even paying people to relocate to the region.

Key to this is development of new energy projects using the northern sea route to export oil and gas to overseas markets, as it becomes navigable for longer each year.

As a means to attract investment, the government has outlined four main types of projects for development:

- Extraction of hydrocarbons offshore;

- Extraction of hydrocarbons on the Russian continent, with an emphasis on developing LNG and gas-chemicals projects;

- Production of LNG and other projects related to gas-chemicals;

- Other projects including extraction of minerals, and various infrastructure projects, such as seaports and pipelines.

BPA-2035 outlines various incentives to attract interest for such projects.

A key factor behind this is Russia’s determination to stop further depopulation of the Russian Arctic region by increasing its attractiveness through new economic opportunities and job creation.

There are two key drivers underpinning Russia’s Arctic policy:

- Production and export of LNG, which over the next 15 years, could turn Russia into one of the largest players on the global LNG market. Central to this are Yamal LNG and Arctic LNG 2.

- Opening up the northern sea route, intended not only to give Russia access to natural resources in the Arctic, but also to provide a maritime corridor for Chinese goods travelling to the EU. Russia aims to solidify its role as the main transportation artery between China and Europe both on land and by sea.

Russia also proposes to create a new state corporation, ‘Rosshelf,’ “specifically tasked with the exploration and extraction of hydrocarbons in the far north and the far east. Accordingly, this corporation should be given exclusive rights to represent Russia’s interests and to exploit Russian resources and grant the right to participate in projects to private investors.” Russia sees the promotion of “mutually beneficial economic partnership with Arctic and non-Arctic states” as an objective for Arctic co-operation. So far there has been some competition with Canada, Norway, Denmark and the US. This becamd visible when Russia planted its flag on the seabed under the North Pole in 2007, claiming the Lomonosov Ridge extended that far.

BPA-2035 details Russia’s strategic interests, scope, ambition and mechanisms to develop the Arctic region. It is, therefore, not surprising that it introduces the concept of “ensuring sovereignty and territorial integrity” at the top of the country’s national interests.

Interestingly, the document was published just ahead of Russia chairing the Arctic Council in 2021. BPA-2035 identifies this as “the key regional institution co-ordinating the international cooperation in the Arctic.”

But with Asian economies – seen as the primary market for Russia’s Arctic resources – slowing down and oil and gas prices remaining low, it remains to be seen how far Russia’s plans to develop the Arctic region can go in realising their potential. Certainly, so far, Novatec has been very successful in demonstrating how this potential can be turned into commercial reality.

Challenges

The first draft of ES-2035 was prepared in 2015, but it took four years before it was revised by Russia’s energy ministry in October 2019 and submitted to government, to be finally approved in April. This inordinate delay may be related to a lack of consensus between key government and industry players about the direction of energy policy, possibly owing to the rapid and far-reaching changes in the global energy sector.

Or it might be because of the longevity of the regime: most governments try to rush things through to be sure of leaving a monument. Now in his late 40s, Novak has been minister since 2012, barring a brief period in January when the government resigned temporarily.

Either way, energy strategies that look so far into the future risk being wrong-footed by events that continue to shake global oil and gas markets.

Several crucial but politically sensitive energy issues still need further clarification of policies. These include:

- a future fiscal regime for oil and gas that could incentivise output and prevent production declines;

- industrial and technological policy;

- the choice of the future model for Russia’s gas industry and whether it is going to develop under continued state regulation or in a market environment;

- climate policy and the strategy to promote renewables and other technologies of energy transition;

- the future of competition in wholesale and retail power markets.

It is also unclear how Russia will address its huge dependency on hydrocarbon exports and how it plans to compete in a fast-changing global energy market.

Given the increasing challenges the oil and gas sector is facing globally, including low prices and declining markets, Russia needs to consider further diversification of its economy. How this can be achieved is not clear in ES-2035.

International sanctions against Russia have reinforced internal trends toward a greater role of the state in the Russian economy at the expense of openness and market-driven policies. In addition, pivot to the east has made Russia more dependent on China, which brings its own vulnerabilities. But it at least provides a balance to its dependence on gas exports to Europe, which can have its own challenges as the problems of constructing Nord Stream 2 have shown.

Despite identifying Europe and Asia-Pacific as the key markets for Russian energy exports, ES-2035 does not present a detailed and comprehensive strategy of how this will be achieved in the longer term, particularly given the rapid changes in these markets.

But as long as its economy remains dependent on oil and gas income, it will continue being exposed to shifts in global energy prices. Another short-coming is that ES-2035 does not take into account the possibility of declining export demand in the future.

What is clear though is that during the next 15 years Russia is going to remain an energy powerhouse and one of the largest world oil and gas exporters.