Russia’s contaminated oil [NGW Magazine]

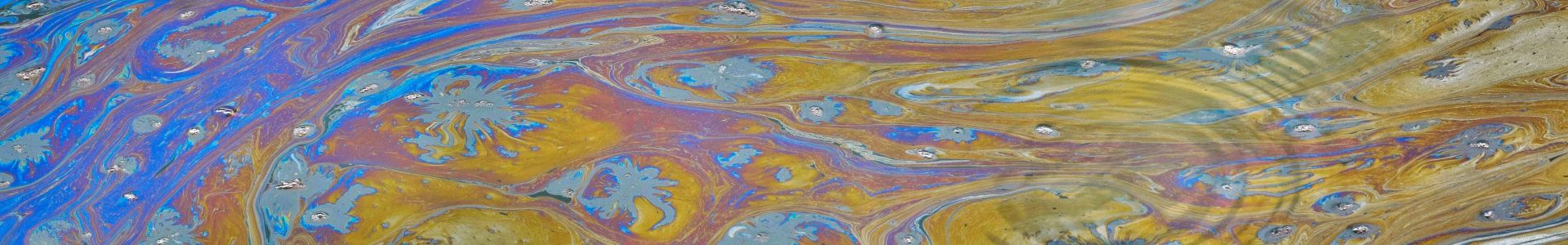

In April 2019, the major Soviet-era Druzhba oil line received a large amount of polluted oil, which duly moved through several European countries, including Belarus, Ukraine and Poland, and into Germany.

So far there has been no clear explanation of how this came about. Some have said it was sabotage by one of the Russian oil companies seeking control of the operator, state-owned Transneft.

The pollution not only created problems for Russia’s oil delivery, and Russia’s economy in general, but also might create serious problems for the building of Nord Stream 2 (NS 2), giving the project’s many enemies reason to claim that it is not ecologically or environmentally safe.

Economic implications and demands for compensation

The event in itself is a serious blow to Russia’s economy. The losses were manifold. First, the tainted oil had to be pumped out of the pipeline at considerable expense. The first attempt was unsuccessful, and some observers implied that a complete cleaning of the pipeline was impossible, and that Moscow does not actually have a “Plan B” for exports by land. Second, there were few buyers for the oil, tainted with acidic chlorides. Third, the incident provided a good excuse for countries which have issues with Russia to demand compensation and other concessions. This was, for example, the case with Belarus, which is officially a “union state” with Russia, mostly for economic reasons, including cheap gas and oil. But problems have emerged periodically, and Minsk and Moscow have engaged in periodic “gas/oil wars,” with Moscow able to reduce benefits for Minsk. The Druzhba disaster coincided with a new round of oil/gas wars. Minsk became embittered and even threatened to part company with Moscow. The problem with oil also provided Belarusian leader Alexander Lukashenko with a reason to demand considerable compensation for real and imagined damages.

Minsk said the tainted oil reached the Mozyr refinery April 22 and seriously damaged the facilities. The day after, Belarus stopped deliveries of oil products to Ukraine, Poland and the Baltic states and said repairing the damage would cost least $30mn, while it would claim a much larger sum as compensation for the broader economic damage done.

Minsk was not alone in its complaints and demands for compensation. Kazakhstan, supposedly a close ally and member of the Eurasian Union with Russia and Belarus as co-founders, also demanded compensation.

Still, the most serious problems could be caused by the tarnishing of Russia’s image as a reliable and safe deliverer of not just oil but also gas.

Druzhba disaster and implications for NS 2

Those who strongly oppose NS 2 have long pointed out that Russia has a weak claim to be considered a reliable source. One of the major arguments was Moscow’s penchant for using gas supplies as a way to promote its geopolitical interests. And they could usually point to gas wars which Russia waged against its western neighbours, most clearly with Ukraine. Moscow usually discounted this notion and alleged that the conflict with Ukraine and interruption of the gas delivery was due not to geopolitical but purely economic reasons: Ukraine did not pay for gas it had received, and had even stolen some of the gas sent to Europe. Still, those who objected to NS 2’s construction insisted that Moscow was driven not just by economic, but also by geopolitical, interests, and was not to be trusted. Washington, anxious to sell American LNG, was especially anxious to present Russia’s gas as less reliable, even if cheap. While possible geopolitical implications have been constantly raised by those who object to the project, and the US is threatening legislation to impose sanctions on companies involved with it, so far the ecological implications of the project have been ignored. In fact, it is Moscow that has drawn attention to the problems of ecology associated with subsea gas lines, albeit in the long-way-off Caspian.

For a generation, Turkmenistan had wanted to build a gas line which would provide it with the opportunity to send gas to Europe. Anglo-Dutch major Shell and US engineers Bechtel were among the companies eyeing this new route in the late 1990s. But Moscow vehemently resisted this plan, and built up the Caspian Sea navy to buttress its argument with threats. By 2018, one could assume that Moscow had finally relented, as it had formally conceded that the Caspian Sea states, including Turkmenistan, had the right to build gas lines. But there is no sign that Turkmenistan has engaged in this kind of activity or has even assembled a team of potential investors. The permission to build gas lines is conditional, by the agreement of Caspian Sea states, on the project being ecologically safe. If any of these states announce that they have reason to suspect such a project is not safe, from an ecological point of view, that can be enough to stop it. And one could assume that Russia would do this, and use force to back up its argument, given the way it has continued to strengthen its Caspian Sea fleet. The same ecological concerns were also quite important – at least in the Kremlin’s propaganda – in dealing with Ukraine. While insisting on the importance of NS 2, Moscow stated that the Ukrainian gas lines were quite unreliable: they are old and could explode. However, now the same tactics could be used by Denmark, which has still not provided permission to build NS 2, and has demanded an extensive formal assessment of the environmental risk the project poses.

This might take months, and delay the construction for some time. One could wonder what kind of conclusion the Danes will make in regard to the ecological dimensions of NS 2. Still, it is clear that the present-day problems with tainted oil have created additional problems for Moscow and could potentially undermine the country’s reputation as a predictable supplier of either oil or gas.

Denmark, the environment and Nord Stream

Denmark is the only country that has not issued a final permission for NS 2 to use its seabed, making it hard for the builders to schedule the construction work over the peak period, the summer; and ecological considerations are quite important for Copenhagen. At least, this is what the Danish officials told the public.

The Danish Energy Agency (DEA) has requested from NS 2 company an environmental assessment of an alternative southern route further south of Bornholm in the country’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) but not the territorial sea, a much narrower stretch of water through which NS 1 passes. That route was initially allowed and then was retracted when the foreign ministry took control of the decision-making process on security grounds, as it made the process too uncertain. NS 2 then considered two new routes, one of which only became available this spring when a decades-old Poland-Denmark territorial dispute ended in Denmark’s favour, with Poland ceding more water to the south of Bornholm than it previously allowed.

That might have been linked to Poland’s need for a treaty with Denmark governing the Baltic Pipe, carrying Norwegian gas to Poland across Denmark.

The DEA is carrying out an assessment on how the new Gazprom-backed gas pipeline from Russia to Germany would affect the environment in its EEZ of the Baltic Sea. There was the suspicion that Denmark had been dragging its feet in the hope that the European Commission would simply block the project on legal grounds before it had to give its approval.

Copenhagen found no problems after the initial assessment, when it said that all the risks had been assessed in accordance with DNV-GL standards to be negligible, low or within the acceptable region. But that did not mean that the threat had passed. In 1945, 50,000 tons of chemical weapons were sunk in the sea near the Dutch shores, and Copenhagen was concerned that NS 2 could disturb them, leading to serious damage to the environment, and the assessment of that risk could take several months. All of this implies that NS 2 could well not be finished by the deadline, launched at best in the middle of 2020. The delay could be as long as a year, and this was acknowledged even by Russian observers. Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller also acknowledged that the launch of NS 2 could be delayed – if not stopped for good as some have claimed.

These clear attempts to delay the construction of the project, or the actual desire to stop it completely on the basis of various excuses, have outraged Gazprom. The European Commission has always said it would seek to regulate, not halt, NS 2. The Swiss-based project company NS2 AG has written to the president of the European Union, Jean-Claude Juncker, invoking Article 26 of the Energy Charter Treaty, seeking guarantees of fair treatment – in particular the fundamental principles of non-discrimination and the protection of legitimate expectations.