Russia – climate saviour and winner of the energy transition? [GasTransitions]

There is no country in the world that will be affected more by the energy transition than Russia, the world’s largest fossil fuel exporter. Is the country prepared for this challenge? Or will this be Russia’s Kodak moment, asks Indra Overland, head of the Centre for Energy Research at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and Professor at Nord University, in an article in the February 2021 issue of Oxford Energy Forum dedicated to “The Geopolitics of Energy”. Perhaps surprisingly, according to Overland, although Russia may go down with the fossil fuel age, at the same time there is no country that’s in a better position to profit from decarbonisation than Russia.

How Russia will deal with the energy transition matters a lot – both to Russia itself and to the rest of the world, Overland points out. “Unlike Saudi Arabia – with which it vies for pre-eminence as the world’s largest oil exporter – Russia is also the world’s largest gas exporter and third-largest coal exporter. Fossil fuels play a pivotal role in Russia’s income, employment, power on the international stage, and identity. Russia also has the world’s second-largest nuclear arsenal and the world’s largest territory, giving it a major presence in Asia, Europe, and the Middle East alike. There is, therefore, also no other country whose fate in the global energy transition will matter as much to the rest of the world.”

According to Overland, there are several reasons to think that the Russian leadership are “not particularly well prepared” for the changes in the energy sector. First, “the Russian petroleum industry is one of the oldest and most entrenched in the world.” Secondly, “Russian actors have a weak track record of anticipating and preparing for change in the energy sector.” As an example, he cites the oil price instability in the 1980s which contributed to the demise of the Communist Party, and the shale gas revolution which was belittled for a long time by Russia’s gas executives.

Thirdly, “the Russian government sends out mixed climate policy signals.” It is not clear, Overland suggests, whether or to what extent Russian leaders take climate change seriously.

Political momentum

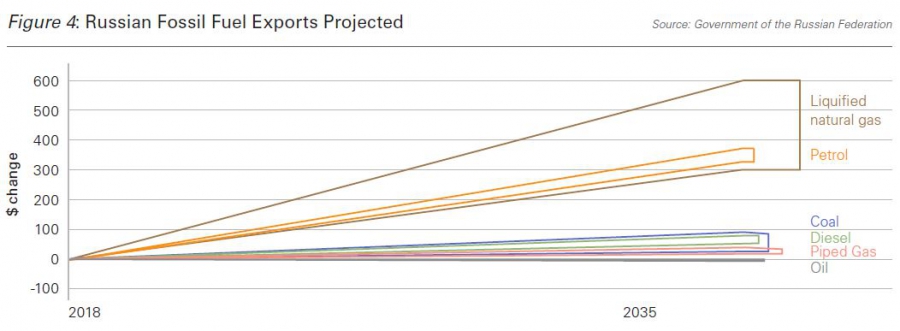

In its official projects, the Russian government foresees a significant rise in its fossil fuel exports, notes Overland. “It expects that only crude oil exports will decline, and that is because the government plans to refine more oil domestically and export higher-value refined products instead. In its most bullish scenario, it expects up to 86 per cent growth in coal exports, 373 per cent growth for petrol, and 603 per cent for liquified natural gas. Even in the government’s most modest scenario, substantial growth is expected.”

Overland suggests that these projections might well be way too optimistic. “One of Russia’s main decarbonisation bets is on natural gas as a transition fuel and on the EU needing to import more of it to replace its own declining production. A decade and a half ago, this line of thinking was dominant in the EU, too. However, more and more EU countries are placing their bets on renewables, electric vehicles, and green hydrogen rather than natural gas.”

In addition, Overland notes that “the price of emissions allowances in the European Emissions Trading System rose 665 per cent between 2017 and 2021. The EU’s proposed Green Deal involves further raising the price of greenhouse gas emissions substantially.” The EU is also planning to introduce carbon border taxes. “This means that companies exporting to the EU will face similar emissions costs as those based within the EU. “

More generally, “the pro-climate political momentum is stronger than ever” throughout the world, writes Overland. Investments in renewables and batteries are soaring.

Trouble

All of this spells trouble for the Russian fossil fuel state. Nevertheless, Russia has plenty of options to deal with the change, according to Overland. The country “has the world’s largest solar power resources [!], second-largest wind power resources, and fourth-largest hydropower resources (Overland et al., 2019). Only two G20 countries have greater renewable energy resources per capita than Russia: Australia and Canada. Accordingly, Russia could produce renewable energy for export, in the form of electricity or hydrogen or embedded in energy-intensive goods.”

Russia is also rich in minerals. It has “the world’s third-largest reserves of nickel (a key component in electric vehicle batteries), fourth-largest of copper (used for electric turbines, motors, and cables), fourth-largest of rare earths (used for several technologies), and seventh-largest of uranium (used for nuclear power). In terms of minerals and mining, Russia clearly has a contribution to make to the energy transition.”

Russia could also opt to produce “blue” and “turquoise” (from methane pyrolysis) hydrogen on a large scale. “In fact, no other country in the world has as much vested interest in the success of blue/turquoise hydrogen as Russia,” notes Overland.

The Norwegian researcher concludes that “Russia could go from being a major victim of decarbonisation to becoming its saviour. The energy transition is indeed a high-stakes game for Russia.”

|

“Russia needs regime change” The “current Russian business model, going all in for fossil fuels, will not be sustainable,” write Dutch researchers Jilles van den Beukel and Lucia van Geuns in a paper for the The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (HCSS) published in January 2021. Van den Beukel and Van Geuns note that “over the last decade, revenues from oil and gas production accounted for 40 to 50% of the Russian federal budget and about two-thirds of Russian exports, percentages that are higher than those for the Soviet Union in the 1980s.” However, “many countries have now started to decarbonise their energy systems”, and the Russian government “chooses to ignore” this. According to the authors, the current regime is too much invested in the fossil fuel sector to be able to change this. “A more sustainable business model, competitive in other industry segments, requires a more open and less corrupt society, effectively implying a regime change.” |