Project spotlight: Abadi LNG [LNG Condensed]

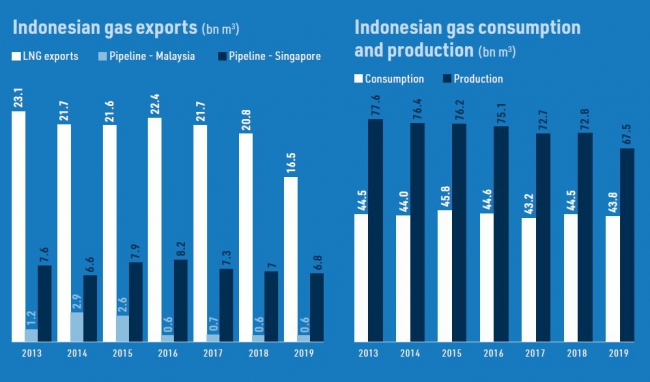

Declining gas output continues to affect the amount of gas available for export, both by pipeline to Malaysia and Singapore, and as LNG as Indonesia continues to consume more of its own LNG production itself.

New LNG projects are the primary means of reversing the country’s slide towards becoming a net importer of LNG. However, in September, it was reported that Train 3 at BP’s Tangguh LNG plant had suffered further delays as a result of labour restrictions relating to the Covid-19 pandemic. The train is now expected to start production in the fourth quarter of 2021, raising capacity at the facility by 3.8mn metric tons (mt)/year to 11.4mn mt/yr.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

Abadi gas field

Development of the Abadi LNG project would make a much greater difference. The Abadi gas field contains an estimated 283-340bn m3 of gas, but despite some advances, the project has yet to receive a final investment decision (FID) some 20 years after the field was first discovered.

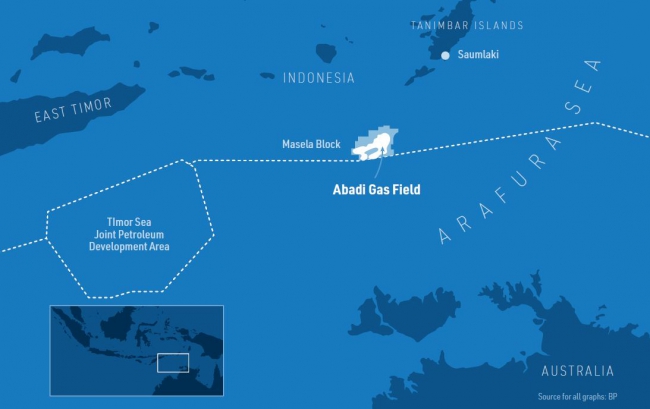

The field lies in the Masela block in the Arafura Sea in eastern Indonesia, covering about 2,500 km2, 150 km offshore Saumlaki in Maluku province. Nine appraisal wells were drilled on the field at different times between 2000 and 2014. The concession is owned 65% by Japan’s Inpex and 35% by Anglo-Dutch major Shell.

Given the field’s remote location, the initial plan was for a floating LNG plant, but following a decision by Inpex to delay the project’s development, the government sent the company back to the drawing board in 2016 with instructions to develop the gas field as an onshore development. A revised development plan for a 9.5mn mt/yr LNG plant were submitted in June 2019 with a projected price tag of $20bn. The field is also expected to provide additional gas via pipeline for local use and up to 35,000 b/d of condensate.

The plan was accepted by the government in July 2019 and included an additional seven-year time allocation for development and a 20-year extension to the production sharing agreement (PSC) expiring in 2028, extending the term of the PSC to November 15, 2055.

Contracts awarded

In May 2018, engineering company KBR was awarded the pre- front-end engineering design (Feed) contract for the onshore LNG processing plant, as well as for supporting utilities, storage tanks and export facilities, while in June the same year, the pre-Feed contract for subsea umbilical risers and flowlines and the gas export pipeline facilities was awarded to a consortium of Chiyoda Corp and PT Synergy Engineering.

In February last year, two memoranda of understanding (MOUs) were signed with PT PLN and PT Pupuk Indonesia for long-term domestic supply of LNG and pipeline gas supply. PT PLN is responsible for the majority of the country’s power generation and electricity distribution and transmission, while PGN operates the gas transmission and distribution grid.

The agreement on pipeline gas was for 4.2mn m3/d to be supplied to a co-production plant to be constructed by PT Pupuk Indonesia.

The contract for marine survey works was awarded to Fugro in March 2020, including geophysical and geotechnical surveys to support the Feed for the offshore production facilities and subsea pipeline to the onshore LNG terminal.

On December 4, Inpex announced that it had signed a further MOU with PT Perusahaan Gas Negra Tbk (PGN), Indonesia’s main national gas company, for the domestic supply of LNG from the project.

The MOUs mean that the project is progressing in terms of lining up its domestic gas obligation, but international buyers are still needed for additional offtake. In addition, final engineering plans will depend on the result of the marine survey works. According to Inpex, production will start up in the latter half of the 2020s, but an FID is unlikely without additional offtake agreements.

Moreover, there are persistent reports that Shell is looking to divest its stake in the project, although this position may have changed as a result of the write down last year in value of oil and gas assets. Consultants Wood Mackenzie have commented that a divestment is more likely when the project gets close to FID.

Net importer timing

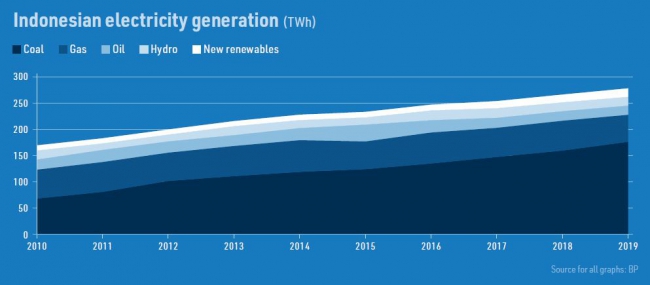

There is little question that Indonesia itself needs more gas, owing to the combination of declining domestic production and rising demand. The government plans to raise gas’s share of the energy mix from 18.1% in 2018 to 22% in 2025. This is likely to see an ever greater share of Indonesia’s LNG production consumed domestically. Jakarta has already announced that pipeline exports to Singapore will stop in 2023 and be diverted to the domestic market.

According to a study by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES), The dilemma of gas importing and exporting countries, published last August, which assumes both the development of Abadi LNG and completion of Tangguh Train 3, the government estimates that domestic LNG demand will offset natural gas exports by 2028 and the country would then become a net importer. All gas exports would cease by 2034.

A more conservative OIES estimate, which sees domestic gas demand grow more in line with historic rates, suggests the country will become a net gas importer in 2030.

The report says that maturing fields and unattractive upstream incentives are retarding production gains as developers shy away from developing more expensive gas fields, while at the same time a growing population and industrialisation are pushing up domestic demand. Moreover, pressure has grown for energy subsidies and a gas price cap for large consumers has been introduced. These, along with growing obligations to supply the domestic market, make new gas production for LNG projects even less likely.