Pretoria addresses the blackouts [NGW Magazine]

South Africa is the continent’s most industrialised economy and it also has the biggest energy consumption per capita, owing to its heavy industry and mining. The International Energy Agency (IEA) put this at 2.3 metric tons oil equivalent (mtoe) in 2018 – above the world average 2 mtoe and almost three times as much as Africa’s next biggest, Nigeria, which weighs in at 0.8 mtoe/capita.

But the country has suffered from crippling black-outs for over a decade and this is preventing economic growth. In order to address this the government last October approved the Integrated Resource Plan ‘IRP 2019.’

The plan addresses electricity supply and demand to 2030, pursuing a diversified energy mix that pays due respect to security of supplies and the environment. The last such plan was IRP 2010 but the problems with blackouts started as long ago as 2007.

The release of IRP 2019 coincided with yet more unplanned outages and rolling blackouts – the widest blackouts ever being witnessed in December, with an estimated 40% loss of power generation capacity – that have continued this year. Repeated nationwide blackouts throughout 2019 dragged South Africa’s economy into contraction.

Failure to reform near-bankrupt state companies, including the troubled electricity monopoly Eskom, coincided with sharp declines in all economic sectors and growing state debt; and corruption continues to destroy value. Last year was the sixth year of declining GDP per capita, and in December, the IMF concluded: “With low growth and low job creation, the increasing labour force is projected to exacerbate unemployment pressures, poverty, and inequality.” It is not surprising that the country’s credit-rating has been lowered by the agency Moody’s from stable to negative.

Eskom, the country’s biggest state-owned company and responsible for 95% of electricity supply, can no longer keep up payments on its $30bn debts and carry out proper maintenance.

In this context the country’s president, Cyril Ramaphosa, said after the release of IRP 2019: “The latest round of load shedding makes even clearer the urgency with which we must act to protect our energy supply.” He added: “The updated IRP takes into account the constraints that are facing Eskom and electricity users’ desire to have alternatives to meet their energy requirements… The IRP supports a diversified energy mix that includes coal, natural gas, renewable energy, battery storage and nuclear power.”

He also confirmed the appointment of a new permanent Eskom CEO who, together with a strengthened board, has been tasked with “turning the entity around.”

IRP 2019

The plan envisages a range of scenarios under which power demand grows at between 1.3%/yr and 2%/yr until 2030 before slowing to between 1.2%/yr and 1.6%/yr between 2030 and 2050.

A key aim of IRP 2019 is to reduce reliance on coal: South Africa is the world’s seventh largest coal producer, with 85,000 people working in the industry. Coal’s share of power generation in 2018 was 89%. It also provided 74% of the country’s primary energy.

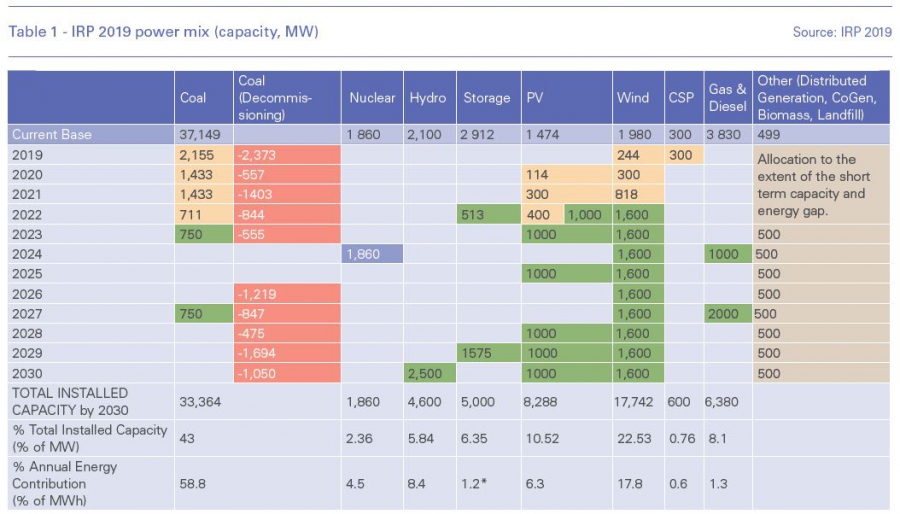

The government plans to decommission 5.7 GW of old coal-fired capacity by 2023, and another 5.3 GW by 2030. However, it also plans to commission 7.2 GW of new, high efficiency-low emissions (HELE), coal capacity this decade (Table 1). The net effect is to reduce coal’s contribution to South Africa’s installed power capacity to 33.4 GW, or 43%, from 75.5% in 2018, generating 59% of the country electricity demand by 2030.

The gap will be filled largely by renewables, through the addition of 6.8 GW of solar PV and 15.8 GW of wind capacity. This will take wind’s contribution to 17.7 GW, or 22.5% and solar PV to 8.3 GW, or 10.5%. Hydropower will account for 5.8% and nuclear and concentrated solar power for 3.1% of South Africa’s power capacity. The IRP also envisages increasing battery storage to 5 GW by 2030.

Natural gas will also play a role, by increasing gas- and diesel-fired unit capacity to 6.4 GW, from 3.8 GW now and providing 8.1% of the country’s power capacity by 2030. This reflects the limited availability of gas resources in the short and possibly medium-term (see below).

Nevertheless, the minister of mineral resources and energy, Gwede Mantashe, expects gas to be an important part of the energy mix after the mid-2020s. In order to support the development of gas infrastructure, Eskom intends to convert diesel-fired peaker power plants to gas

He recognises the flexibility that gas to power technologies can provide to complement intermittent renewable energy and meet demand during peaking hours.

Interestingly, out of the 37.5 GW of capacity to be built by 2030, 73% or 27.2GW will be from clean energy – mostly wind.

Under IRP 2019 Eskom will need to comply with South Africa’s Minimum Emissions Standard (MES) over time. And in an echo of the European Green Deal, the transition towards less carbon-emitting technologies must be fair. Workers and communities in affected areas must, as far as possible, not be left worse off.

IRP 2019 sets out nine supply and demand policies to prevent load shedding and extensive use of diesel peaker plants:

- Create a medium-term power purchase programme to set up reserve capacity;

- Start on technical and regulatory work for the 20-year extension of the life of the Koeberg nuclear power plant;

- Support Eskom financially and legally to comply with minimum emissions standards;

- Convene a team to put together a ‘just transition plan’ within a year in consultation with all social partners;

- Retain the current annual build limits on renewables until the report on the just transition is released;

- Plan for an environment that supports a just transition;

- Support the development of gas infrastructure by converting all diesel-fired power plants to gas;

- Start work on a 2.5-GW nuclear programme;

- Support strategic power projects in neighbouring countries that enable the development of cross-border transmission infrastructure.

Unfortunately energy efficiency measures appear to have been omitted, even though it is one of the goals in South Africa’s National Development Plan (NDP), which states that by 2030 the country should “reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve energy efficiency.”

IRP 2019 is important because it covers the procurement of generation capacity up to 2030. Mantashe is counting on the IRP to lead the country to economic recovery.

It is also the first such plan to shift the focus away from the large-scale, complex, baseload infrastructure South Africa has relied upon for the past 15 years, towards distributed renewable generation that can be developed by the private sector.

IRP also says no more coal plants will be built after 2030 and that 24.1GW coal capacity will be decommissioned by 2050.

In its Africa Energy Outlook 2019, in a section on South Africa, the IEA says:

- Diversifying energy supply away from coal would have many benefits, including a reduction in the number of premature deaths from pollution, but the social implications of changes would need careful management;

- Reforming and restructuring Eskom would strengthen the reliability of the power system, support growing industrialisation and help efforts to diversify the energy mix;

- Strengthening efficiency throughout the economy would reduce demand for both materials and energy, while the implementation of minimum energy performance standards for electric motors in the industry and mining sectors would be an important first step towards unlocking further efficiency gains.

Mantashe has called the IRP 2019 a ‘work in progress’, saying it will be reviewed on a continuous basis – something missing from IRP 2010.

Natural gas

In the short-term the government plans to pursue expanding gas import options from Mozambique’s Rovuma Basin. Some Mozambique gas is already being imported by pipeline into the eastern parts of South Africa by Sasol.

IRP 2019 says that as gas use will be low in the short to medium term, “it will not likely justify the development of new gas infrastructure and power plants predicated on such sub-optimal volumes of gas. Consequently, the development of gas infrastructure will be supported.”

The government also plans to support a first LNG import terminal at Coega, in the Eastern Cape, mostly to support power generation. This could happen as early as 2024 to 2025.

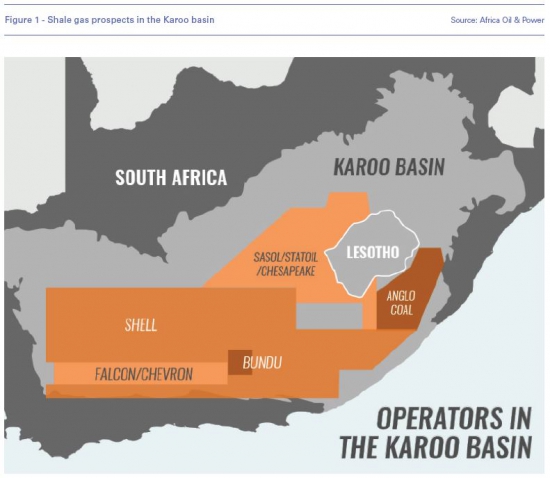

There are also opportunities for coal-bed methane and possibly shale gas. The IEA has estimated South Africa may hold 485 tn ft³ of shale gas. This is mostly in in the semi-arid Karoo basin (Figure 1), where water scarcity might pose problems. An additional problem is that South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) found in July 2019 that the exploration for petroleum by fracking should not take place before it can be lawfully regulated. However, this may now be overcome by the approval of the Upstream Petroleum Resources Development Bill.

IRP 2019 says: “Exploration to assess the magnitude of local recoverable shale and coastal gas is being pursued and must be accelerated.” In the longer-term domestic gas resources could be adequate to enable power generation but at present, local demand for natural gas is limited to some industrial and domestic use.

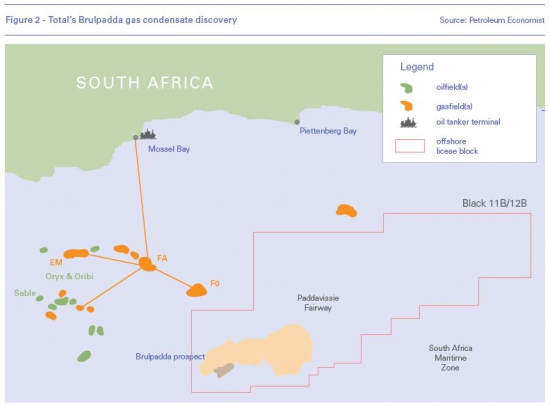

The medium-term future may lie with Total’s offshore gas discovery Brulpadda, in the Outeniqua Basin off Mossel Bay (Figure 2). This could open a completely new petroleum and gas province in Southern Africa. The French major said: “With this discovery, Total has opened a new world-class gas and oil play and is well positioned to test several follow-on prospects on the same block.”

It is in an area where other oil, gas and gas condensate discoveries have already been made and developed. But Brulpadda is the first to be drilled in the promising Outeniqua Basin and in deep-water. However, metocean conditions could be challenging.

The Brulpadda gas block was discovered by Total in February 2019. It covers an area of 19,000 km², and the discovery is about 175 km south of Mossel Bay. Total announced that it found a potential 1bn barrels oil equivalent of gas and gas condensates in the block. Recoverable quantities are still to be confirmed. Since then Total has completed further 3D seismic surveys and it is now planning to continue its drilling programme during Q1 2020.

With the government and Total signing an MoU last year giving the company complete rights to operate, gas from Brulpadda could start flowing in the mid-2020s.

But if domestic demand remains limited, gas condensates would have to be exported to make exploitation commercially viable.

Other majors with interests offshore South Africa include US ExxonMobil, Italian Eni and Norwegian Equinor, but they have not yet carried out any drilling.

Development of onshore and offshore gas prospects requires regulatory certainty. But progress with proposed changes to the Mineral and Petroleum Resource Development Act (MPRDA) has been slow. However, last year, the government took steps to split off the petroleum aspect of the bill from the mining, a move welcomed by the gas industry.

On January 6, the government approved the publishing of the draft Upstream Petroleum Resources Development Bill for public comments by 21 February. Once finalised, it should provide greater policy certainty and a stable environment for investment in the South African oil and gas sector.

The bill provides for the state to receive a 20% free stake in all projects, which must also have a minimum of 10% black ownership – both of which demands will challenge investors. The other problem is that taxes and royalty regimes still need to be drawn up by the finance minister. It remains to be seen if this will attract the investment needed to kick-start the sector. The longer this takes to put in place, the longer it will take to bring Brulpadda into production.

In addition, the government plans to issue an amendment to the Gas Act of 2001, to be tabled soon. The purpose of this will be to support gas-to-power projects, planned after 2023 (Table 1), to complement intermittent renewable energy.

The new Bill and the discovery of Brulpadda could reinvigorate exploration in the region.

Carbon emissions

In 2018 South Africa’s energy sector accounted for about 80% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), of which half came from generation.

Even though IRP 2019 states that coal plants will have to meet the country’s emissions standards – set up in IRP 2010 – so far Eskom has been applying for and receiving postponements on the basis that retrofitting plants is too costly. This obviously defeats the purpose of the emissions standards.

Carbon Brief states that “South Africa is the world’s 14th largest emitter of GHGs. Its CO2 emissions are principally due to a heavy reliance on coal.”

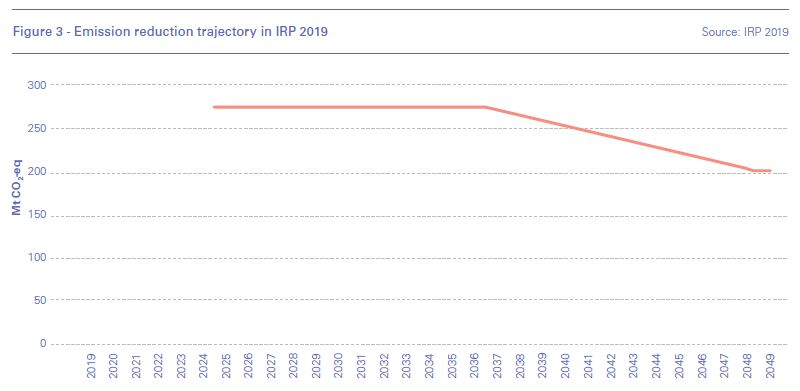

In response to the Paris Agreement, South Africa pledged that its emissions would peak between 2020 and 2025, allowing them to plateau for roughly a decade before they start to fall (Figure 3). Climate Action Tracker rates this as ‘highly insufficient.’

South Africa is at an advanced stage of formulating a National Climate Change Bill on mitigating the effects of climate change and expects to pass this into law in the near future. According to environment minister, Barbara Creecy, its purpose is to ensure the long-term just transition to a climate-resilient and lower carbon economy and society.

The signing last May into law of South Africa’s much delayed carbon tax might also contribute into curbing emissions. It comes into force on 1 June 2022.

The shift to renewables between now and 2030 will help reduce emissions, contributing to South Africa’s drive to meet its Paris Agreement pledges.

It is also one of the key goals in the country’s NDP. It states that by 2030 South Africa should “Produce sufficient energy to support industry at competitive prices, ensuring access for poor households, while reducing carbon emissions per unit of power by about a third.”

Restructuring of Eskom

The biggest challenge to the successful implementation of IRP 2019 is Eskom which may be fundamentally insolvent. Not only due to its massive debt, but it also reported a net loss after tax of $1.4bn for the 2019 financial year. It expects to make a similar loss in the 2020 financial year. This makes it even more difficult for the company to service its debt and invest in plant maintenance and in new infrastructure. About a fifth of its power plants are not operational at any one time.

The company has not built any major infrastructure for 20 years, and as a result it lacks the project management skills. This is exacerbated by rampant corruption at all levels. However, the government has set out plans to restructure Eskom, dividing it into three parts – generation, transmission and distribution – over the next three years. It has also confirmed plans to end Eskom’s near-monopoly over power supply, forcing the company to compete with independent power producers to generate electricity at least cost.

A new CEO, Andre de Ruyter, was appointed early January and has already tabled some ideas to Eskom’s board. He proposes to take longer to consider the potential effects of the company’s unbundling. He said: “For us to rush into full legal separation from day one creates a number of risks: transfer of assets, our lenders will be very concerned about the assets that they have loaned us money against… There’s a lot of planning that needs to go into the unbundling and restructuring of Eskom.”

Key to this will be to urgently get into grips with Eskom’s precarious financial position by restructuring its debts while addressing and shoring up the reliability of its power supply system.

De Ruyter accepts the need for private investment to increase reliable electricity generation, “not necessarily just with renewable energy, but with all sources that make sense.”

Challenges

By shifting emphasis to renewables, the government not only addresses its emissions problem, but it also brings in the private sector with private investment and much-needed project management experience.

With blackouts shutting down mines, the government has already agreed to allow mining companies to generate renewable energy for their own use, without the need for licences.

However, there is criticism of IRP 2019 from environmental NGOs that persistence with high levels of coal consumption is not in line with the president’s promise to address the climate crisis. But new coal power projects may yet face headwinds: environmentally conscious banks and institutional investors are reducing their exposure to coal. In such a situation renewables and gas could come to the rescue.

In fact IRP 2019 states that although there are annual build limits for renewables, in the long run such limits will be reviewed to take into account demand and supply requirements.

In the meanwhile, the biggest challenge is the low level of reliability of Eskom’s ageing coal plants, suffering frequent breakdowns, forcing the company to resort to frequent power cuts, impacting South Africa’s economic output. As a short term measure, the government is trying to procure 2GW to 3GW new generating capacity as fast as possible.

Following a research mission during November, the IMF sounded urgent alarms over South Africa’s economy. Economic growth is set to remain below population growth for the sixth consecutive year in 2020. It identified the inefficient operations of state-owned enterprises in the electricity and transport sectors, and in particular Eskom, as a drain on the country’s economy. The question now is whether South Africa is getting close to an IMF bail-out.

With such deteriorating economic conditions will South Africa be able to carry out the required energy reforms, including Eskom, and implement IRP 2019? It is urgent that it does – as implementation can contribute to the country’s economic recovery – but the country’s governance needs an upgrade too.