Portugal veers from all-electric path to “zero-carbon gas solutions” [GasTransitions]

When he presented Portugal’s new National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) for 2030 at a conference in Amsterdam early in March, João Galamba, the Portuguese Energy Secretary, made it clear that the Portuguese government had made an important “last-minute” change to its climate strategy. “When we compare the first draft [of the NECP] presented at the end of 2018 with the final version, in 2020,” he said, “we can say that green hydrogen was the missing link in our energy strategy”.

Galamba went out of his way to stress that gases, in particular, hydrogen, are now fully in the picture for the Portuguese government. “The role and importance of hydrogen is fully recognized in our final version of our National Energy and Climate Plan.” He said he sees five major roles for hydrogen in Portugal’s future energy system:

- “It is the energy carrier that increases the economic value of electricity produced from renewable energy sources

- It provides a long-term storage solution for renewable energy

- It avoids stranded assets in the energy sector

- It facilitates decarbonization of industry and transportation

- It can be used as a feeding stock for industry”

Galamba made it clear that Portugal does not just believe in the importance of “green” hydrogen, but of all “zero-carbon gas solutions”, including “biomethane” and “natural gas associated to CCS”.

In addition, gas networks, he said, will continue “to be needed to transport and distribute zero-carbon gases”.

According to the Energy Secretary, Portugal is now “working on the new legal framework to initiate the decarbonization of the natural gas grid, setting the technical and regulatory conditions for the injection of hydrogen (and biomethane) into the natural gas transport and distribution grids and extending (and adapting) the system of guarantees of origin/certification for renewable gases.” The government is planning to set a target of 10% of hydrogen in the gas grid by 2030.

A big if

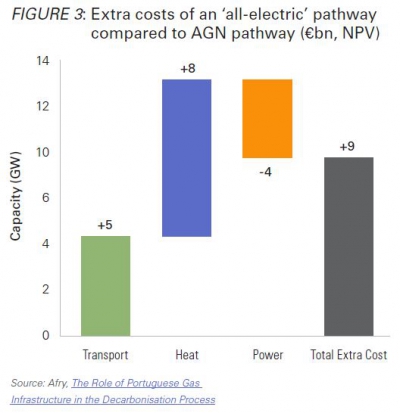

So why did the Portuguese government change its mind and suddenly decided to embrace hydrogen when just two years ago it was still on a course of full electrification? One of the factors, said Galamba, was a study done for the Portuguese gas industry by consultancy AFRY Management Consulting. This study, The Role of Portuguese Gas Infrastructure in the Decarbonisation Process, which was made public in March 2020, shows that Portugal can save a total of €9 billion in the period to 2050 if it continues to use its gas infrastructure compared to taking an all-electric decarbonisation pathway.

This does not mean, however, that the gas industry can take success for granted. Dorian de Kermadec of AFRY, one of the authors of the report, based in Madrid, told Gas Transitions that in order for the gas pathway to be viable, the gas industry needs to produce sufficient quantities of hydrogen and biomethane and it needs to support the development of a carbon capture and storage (CCS) network and storage facilities.

In particular the latter represents a big challenge. CCS currently does not exist in Portugal. The AFRY report concedes that “deployment of CCS is dependent on the creation of an European network to transport and store CO2, as it is assumed that all CO2 produced this way is stored in depleted gas fields in the North Sea, including fields in Norwegian, British and Dutch territories or in more local and suitable aquifers if they are available.” This is a big ‘if’. “Whether all countries choose to adapt and allow CCS to be part of this future will depend on how successful the gas industry is in lobbying and the openness of stakeholders,” notes the report.

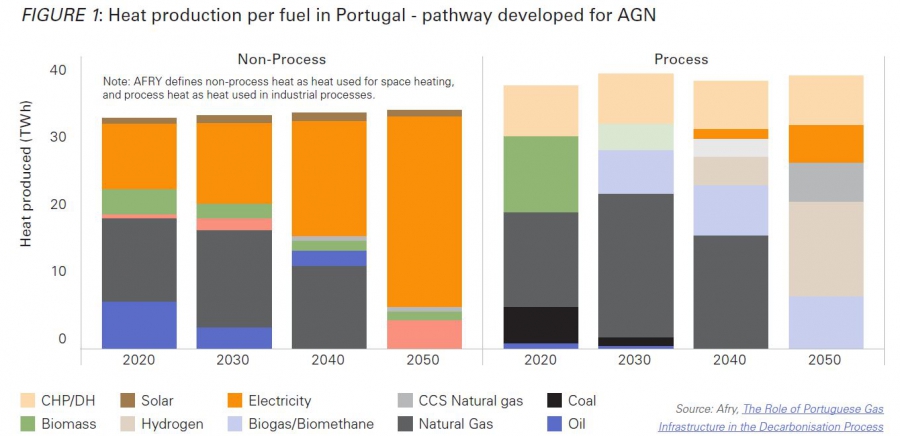

The AFRY report considers three demand sectors: transport, heat (space & water heating and industrial process heat) and power generation. In transport, zero carbon gases only play a limited role. In the space & water heating sector (“non-process”), natural gas is phased out completely, mainly to the benefit of electric appliances or hybrid systems. By contrast, in the industrial sector (“process heat”), most of the heat is supplied by hydrogen as well as biogas/biomethane and “CCS natural gas” (see figure 1).

“CCS natural gas” or “natural gas associated to CCS” refers to CCS technologies used to decarbonise heat production for industrial processes. According to De Kermadec, the AFRY scenario takes the assumption that industrial clusters in Portugal will need CCS technologies in any case to decarbonise their industrial processes, so for heat production they will be able to use either hydrogen (both green and blue hydrogen) or natural gas in combination with available CO2-capture technology.

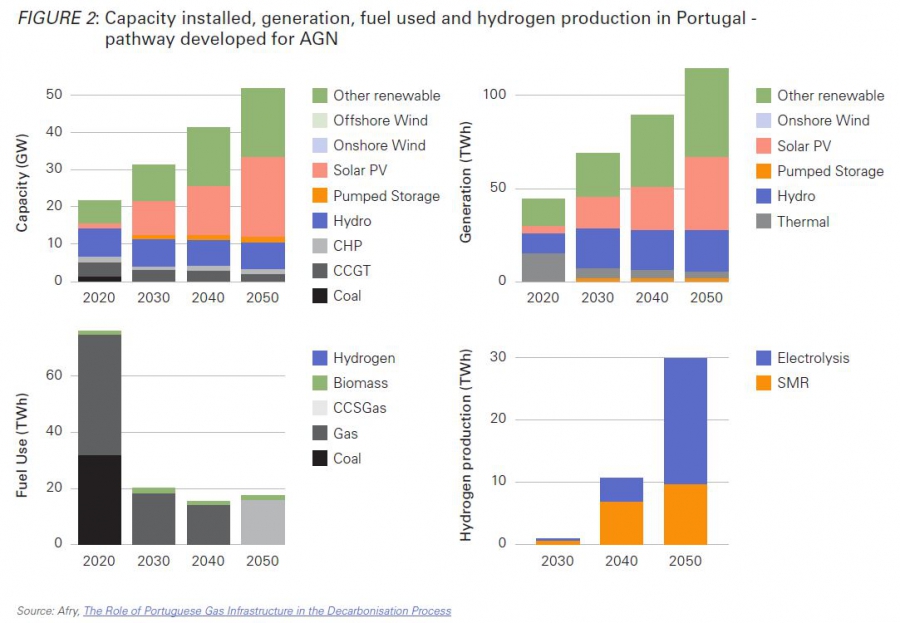

In power generation, the use of unabated natural gas is phased out, but the scenario does allow for a limited amount of back-up gas-fired capacity, using gas power plants fitted with CCS (See figure 2).

Hydrogen demand, in heating and transport, is covered by a mix of blue hydrogen (hydrogen from steam methane reforming combined with CCS) and green hydrogen. As the report notes, “SMR is available from 2030 onwards and increases rapidly between 2030 and 2040, remaining stable until 2050 as electrolysis becomes available by 2040, and alongside the continued high levels of RES deployment it then provides a more cost-efficient way of producing hydrogen.”

The AFRY-scenario leads to higher costs in the power sector, but these are more than compensated for by lower costs in the transport and heat sector, resulting in a total of €9 billion in savings over the whole period (figure 3).

The report does not provide details on the cost assumptions made by the researchers. De Kermadec told Gas Transitions that it was assumed that CAPEX of electrolysis would reduce by >35% between 2020 and 2050 whereas it would decrease more slowly for blue hydrogen. For wind power a cost reduction of 20% was assumed and for solar power 30%, also indirectly leading to lower costs for electrolysis. In addition, it was assumed that CAPEX of CCS would go down by some 30%.

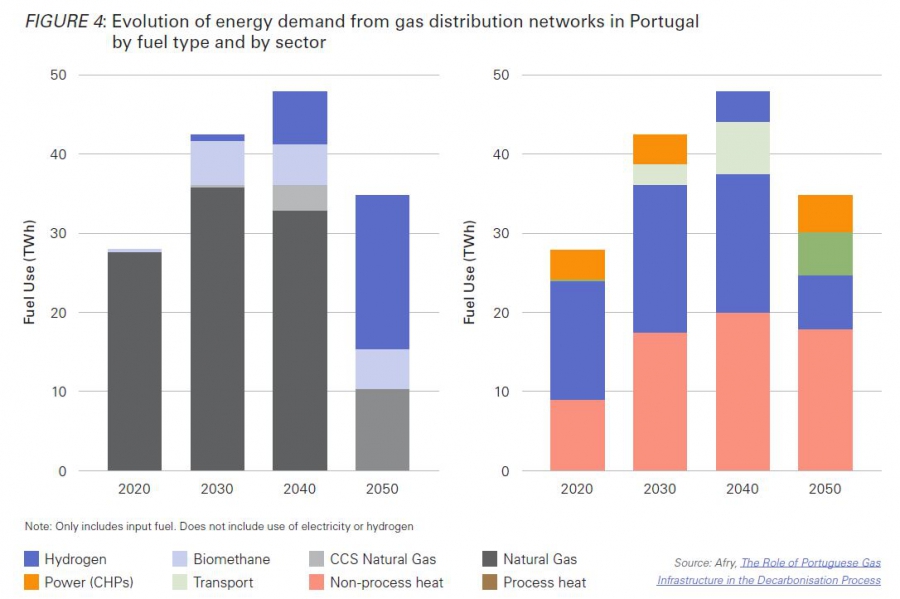

If this roadmap is followed, it will have important consequences for the Portuguese gas distribution networks, notes De Kermadec. As shown in figure 4, which De Kermadec says presents one of the major new insights from the report, the use of the gas networks even increases in the period up to 2040. Only after 2040 does it decline again.

For Portugal, this is important, as the country’s gas networks are relatively young, so this would avoid large stranded assets. Since all the pipelines are made of polyethylene they can be easily converted to hydrogen, notes the report.