Why Oilmen Will Never Be Interested In Renewables [GGP]

As climate change tightens its grip on the world, Congressional Democrats have proffered the Green New Deal, the latest attempt to shift us “away from oil” and toward wind and solar.

While the clean energy transition is vital, a powerful force stands in the way: Profits.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

The oil business consistently provides its investors with very large profits, far above the typical margins around 10 percent among publicly traded companies. Even the other two fossil fuels, coal and natural gas, rarely approach black gold’s consistent profits.

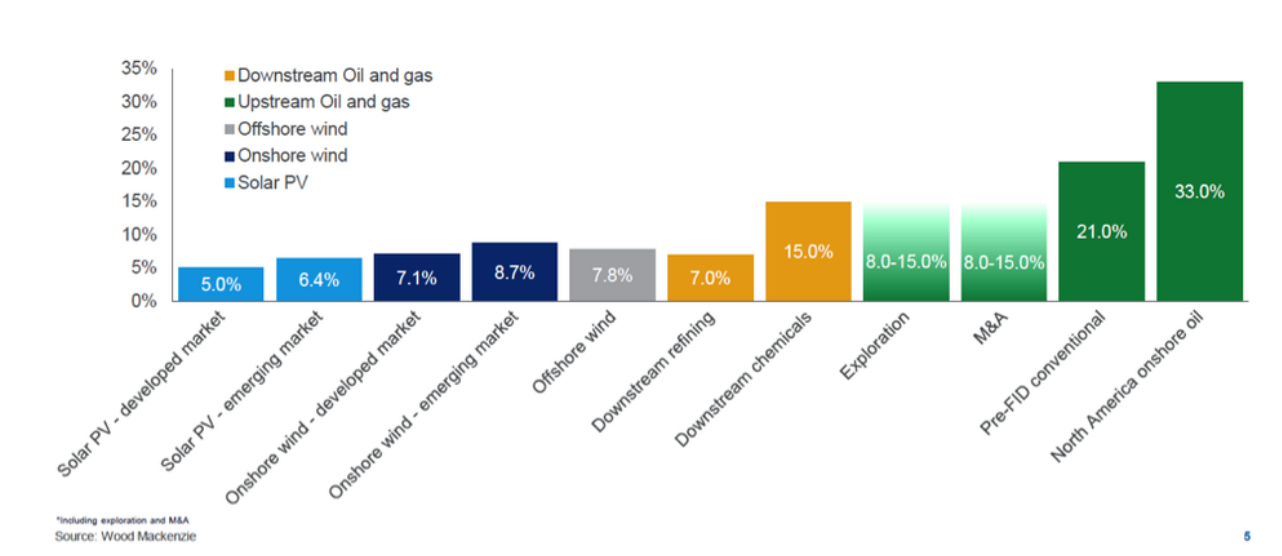

In places like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, where a barrel of oil costs less than $10 to produce and sells for $50 to $100, rates of return are many multiples of those eked out in more competitive businesses. Even in the relatively costly North American shale patch, recent returns hovered around 33 percent, according to consultancy Wood Mackenzie. (Fig. 1)

Figure 1: Internal rates of return for renewable energy projects range between 5% and 9% while those for onshore oil investments in the United States averaged 33%. (Source: Wood Mackenzie, "Oil & gas majors in renewable energy" slide presentation, November 2018.)

Under normal business circumstances, high returns like those in oil attract new entrants into the sector. The resulting competition is supposed to push down profits until they reach reasonable levels.

Exactly that has happened in the wind and solar industry, where innovation and economies of scale have cut costs, including of electricity generated for consumers. But competition has driven down profits, too. Returns on wind projects now average 7 percent, and just 5 percent for solar power, according to WoodMac.

Not in oil.

There, the OPEC cartel’s constraints on production have preserved stubbornly high profits for decades. Since policymakers in places like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait essentially refuse to meet the world’s full demand for oil, the market allows costlier producers, like the shale crews in Texas and North Dakota, to take a share.

Expecting Saudi Aramco or even ExxonMobil to drop oil and shift to clean energy is, in essence, asking them to give up the large profits that they and their shareholders have enjoyed for years, and trade them in for the lower profits in renewables.

“We have much higher expectations for the returns on the capital we invest,” ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods said in a recent interview.

As the Green New Dealers will surely learn, nobody receiving that level of profit will give it up voluntarily – not even if their product is contributing to climate change and, thus, exacerbating wildfires, or, as I saw firsthand last year in Houston, floods that inundated the homes and offices of oil companies and their employees.

Plenty of oil industry folks appreciate the climate benefits of renewables. Few want to invest or work in them. That’s mostly because paltry returns don’t allow for generous pay. Average salaries for engineers at ExxonMobil run upwards of $100,000. At SolarCity, the US installer of solar panels, pay averages $57,000.

That’s typical. Renewables jobs pay about half the salary as comparable oil jobs, and many come with no benefits or insurance. Suniva, the US manufacturer of solar panels, paid just 92 cents an hour to prisoners assembling its panels in 2015.

One way to coax the oil giants to take another look at renewables would be for governments to make oil less profitable by imposing a price for climate damage caused by burning oil, natural gas and coal. The Green New Deal resolution makes no mention of a carbon tax, but such a tax is under discussion in Congress.

The current proposal sets a price of $15 per ton of carbon equivalent emissions, which rises by $10 per year until emissions drop substantially below 2015 levels. The tax would be levied at the refinery or oil import terminal, coal mine, or at the entry point on a natural gas pipeline. Carbon costs would raise prices for consumers, but individual taxpayers would be reimbursed by redistributing revenues from the tax.

A carbon tax would certainly raise US fuel prices. But because transportation services are so valuable – and because there is still no viable substitute for oil in most transport – a carbon tax by itself wouldn’t be enough to discourage driving or bring diversification among oil companies.

Most decarbonization would take place in the power sector, which, in the United States, uses almost no oil. Coal would be the big loser, while natural gas and zero-carbon nuclear and renewables would gain.

For real change in the oil sector, the world – not just the US or Europe – would need the unlikely combination of high consumer prices and low producer prices. High consumer prices would reduce demand for oil by making end-users think twice about buying inefficient pickups and SUVs.

But a low producer price — the global wholesale price for a barrel of oil — is just as important. Low Brent and West Texas Intermediate prices would reduce oil rents and diminish the attractions of investing in oil relative to other parts of the energy sector.

Of course, the world has never seen high oil prices for consumers at the same time as low oil prices for producers. The market intervention required to bring this about would be unprecedented. At a minimum it would require countries to impose big carbon taxes and complementary border tariffs. These protections would be needed to guard against competition from free-riding countries that did not tax carbon.

Nobel laureate economist William Nordhaus advocates such a “climate club” scheme. The Green New Deal hints at these aspirations by proposing trade rules and border adjustments aimed at preventing US businesses from shifting carbon-intense processes offshore.

More likely, change will happen through gains in efficiency and alternative technology – hybrid and electric vehicles and fuel cells – along with government nudges through taxes on fuel and carbon.

The more consumers pay to damage the climate, the easier it will be to convince them to use less oil.

As black gold loses its magic, some oil majors might cast their nets wider. They might try their hand with renewables, perhaps parlaying their offshore expertise into erecting wind farms.

Jim Krane is the Wallace S. Wilson Fellow for Energy Studies at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. His new book is “Energy Kingdoms: Oil and Political Survival in the Persian Gulf.” Follow him on Twitter on @jimkrane

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.