Nuclear expansion plans threaten South Korean LNG demand [Gas in Transition]

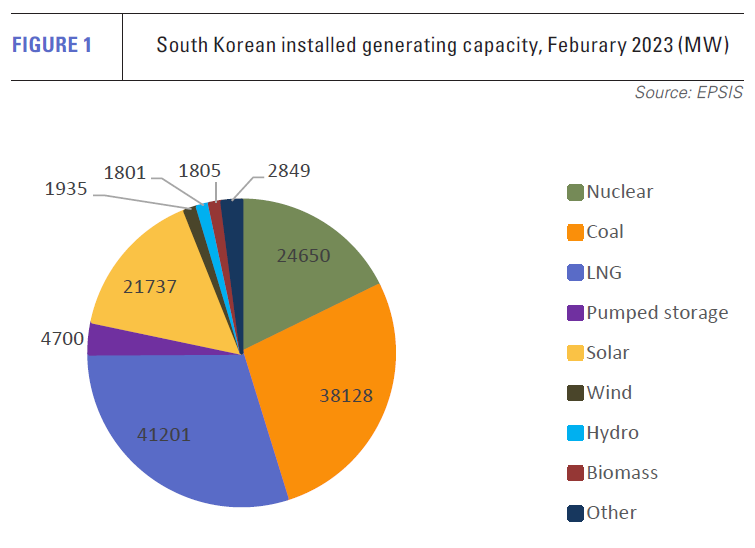

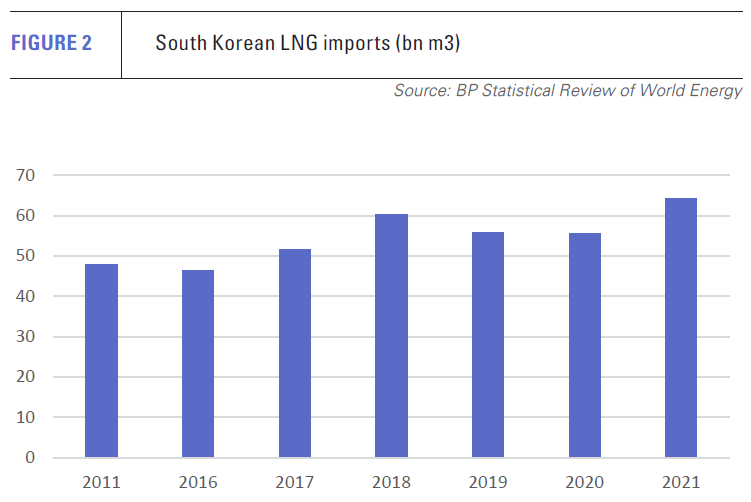

Electricity generation is the main determinant of South Korean LNG demand, with a large and increasing proportion of gas supplies used to produce power (see figures 1 and 2). In 2021, about 51% of gas was used to generate electricity, compared with 46% in 2011, according to data from the Korea Energy Economics Institute (KEEI), with these figures excluding power generated from city gas.

The plans produced every two years by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy are central to any assessment of future demand for gas and thus LNG. South Korean gas is all imported as LNG and the country has next to no domestic production of its own.

10th Basic Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand

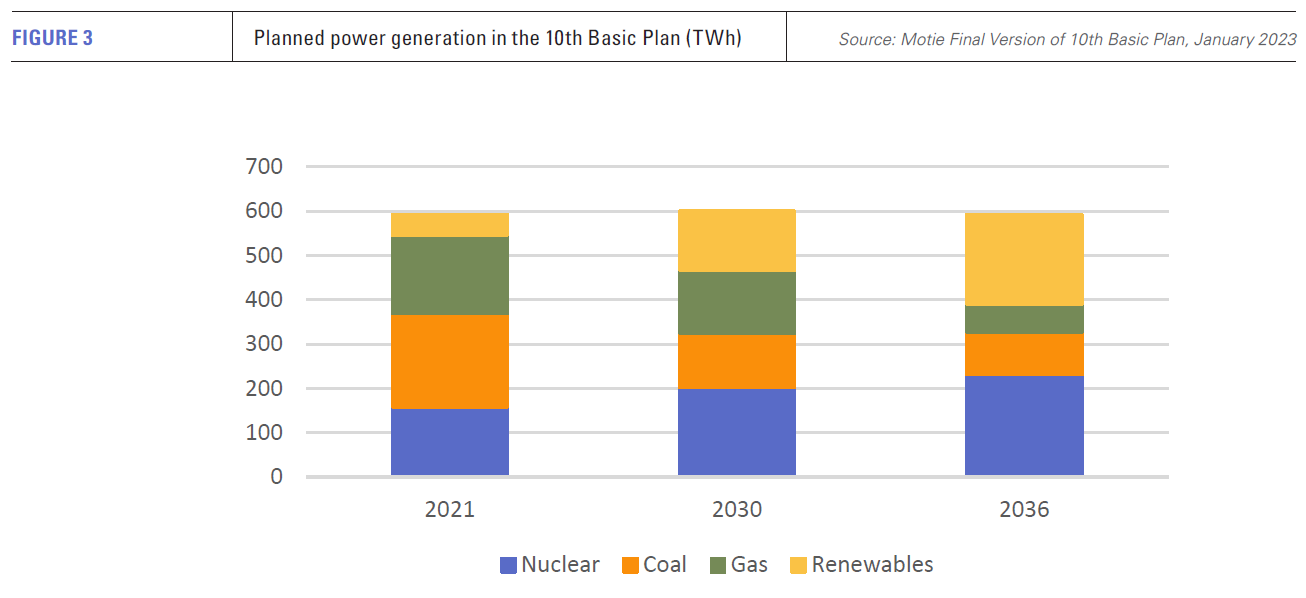

In a sharp turnaround in policy, the 10th plan is focused squarely on nuclear power generation, which is projected to rise from 23.4% of total electricity supply in 2018 to 32.4% in 2030 and 34.6% in 2036 (see figure 3). Six new reactors are due to enter operation by 2033 – four at the Shin Hanul and two at the Shin Kori complexes -- raising nuclear capacity from the current 24.7 GW to 31.7 GW in 2036.

By contrast the 9th plan, published in 2021, envisaged that reactor capacity would shrink to 19.4 GW by 2034, with nuclear generation in that year accounting for only 10.4% of total electricity supply. This was in line with the then government’s nuclear phase-out programme, which mandated that all reactors should be decommissioned once they had completed 40 years of operational life.

The change in the prospects for nuclear energy reflects the very different priorities of president Yoon Suk Yeol from those of his predecessor Moon Jae-in.

Following his election in May 2022, Yoon put the focus on nuclear expansion to ensure energy security and reduce dependence on imported fossil fuels, a focus reinforced by the volatility in international energy markets and war in Ukraine. As well as being intended to boost energy security, Yoon’s promotion of domestic nuclear power is intended to help win overseas reactor contracts.

Gas-fired capacity to increase, but gas burn to fall

The ninth and tenth plans do share similarities. Both envisage that carbon neutrality will be attained by 2050. Both anticipate renewable capacity will continue to increase strongly. However, there is a greater emphasis on wind than solar in the 10th plan. There is also a lower target for renewable energy’s share of electricity output in the 2030s than in the previous plan.

Both plans also envisage that coal use will fall sharply. In the 10th plan, coal-fired generation is projected to account for only 14.4% of electricity output in 2036, compared with 35.3% in 2021. The plan anticipates that 28 ageing coal-fired plants with 15.1 GW of capacity will be converted to LNG use in 2036. This would boost LNG-fired capacity to more than 65 GW.

However, the increase in capacity proposed in the 10th plan does not translate into increased gas-fired generation. In fact, gas-fired output fares very badly in the plan compared with its predecessor. The 9th plan envisaged that gas would account for almost a third of power generation in 2034, whereas the 10th plan envisages that gas’ share will fall to 22.9% in 2030 before plummeting to a meagre 9.3% in 2036.

9.3% of total electricity supply does not necessarily mean a large fall in gas requirements, if it is 9.3% of a much larger total. But this is not the case in the 10th plan, which projects that electricity generation will grow by only 1.4%/yr from the 600.4 TWh posted in 2021. Within that total, gas-fired generation is envisaged to fall from 176.4 TWh in 2021 to 142.4 TWh in 2030 and just 62.3 TWh in 2036.

This would mean a marked reduction in LNG demand from the power sector, which used 23.25mn mt in 2021, according to KEEI data. This is especially so as the average efficiency of gas-fired generating plants is likely to increase as coal-fired steam turbine plants are converted to combined-cycle operation using advanced gas turbine technology.

Too gloomy a prognosis?

At first sight, no. The modest growth projected in total electricity output is in keeping with the growth rate of 1.5%/yr recorded in the sector from 2011 to 2021. Growth in recent years has been below even this level, albeit in part because of the pandemic. While South Korean electricity generation may have topped 600 TWh for the first time in 2021, the figure was only 1.3% higher than the level reached in 2018.

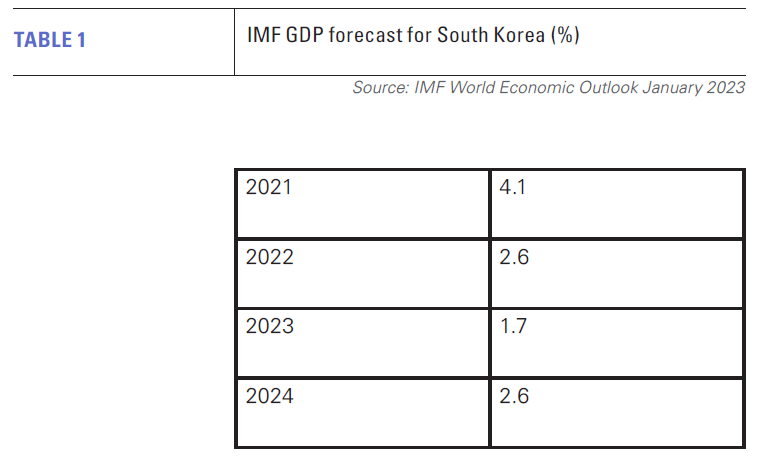

Nor is gas demand likely to be reprieved by a resumption of rapid growth in economic activity. Most domestic and international financial institutions expect that South Korean GDP growth in 2023 will be significantly lower than the 2.6% posted in 2022. GDP began contracting in fourth-quarter 2022 as a result of poor performance by the export, manufacturing and service sectors. Negative or low growth is expected to continue into first-half 2023, driven by declining exports as a result of weakness in the global market exacerbated by the consequences of China’s reopening.

Nor is gas demand likely to be reprieved by a resumption of rapid growth in economic activity. Most domestic and international financial institutions expect that South Korean GDP growth in 2023 will be significantly lower than the 2.6% posted in 2022. GDP began contracting in fourth-quarter 2022 as a result of poor performance by the export, manufacturing and service sectors. Negative or low growth is expected to continue into first-half 2023, driven by declining exports as a result of weakness in the global market exacerbated by the consequences of China’s reopening.

As a result, the financial group ING projected in January that South Korean GDP might grow by little more than 0.6% in 2023. The January edition of the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook was less bearish, but still saw growth of only 1.7% in 2023, followed by 2.6% in 2024. Further out the growth projections become more speculative, but for the most part not more bullish.

Taking these factors into account the 10th plan’s projection that gas-fired generation in 2036 could fall to about a third of that recorded in 2021 does seem possible, providing that the government’s nuclear and renewable targets are met. But that is a very big proviso.

Nuclear plans could be derailed

Achieving the nuclear target is perhaps the most open to uncertainty, given that the decision to shift from nuclear phase-out to nuclear expansion was primarily political in nature. Yoon is one of the most pro-nuclear of all South Korean politicians, and a change in administration could lead to a trimming back or even reversal of the expansion policy.

This is especially so given that public opinion on the subject is highly volatile. High international energy prices and concerns over energy security have given the edge to support for nuclear at present. But the vehement opposition to nuclear power witnessed in the past decade could easily revive as a result of nuclear incidents at home or abroad, or a recurrence of even minor scandals related to the nuclear industry.

The 50% increase projected in nuclear output to more than 230 TWh in 2036 may thus prove very difficult to achieve. And, even if the expansion programme does proceed, maintaining the larger nuclear fleet will require significant gas use during planned and often lengthy reactor outages. The 230 TWh nuclear target is very much a maximum expectation based on reactors operating, and it would be gas that would have to meet the gap resulting from planned and unplanned shutdowns.

The renewable target of more than 200 TWh in 2036 is less problematic in terms of both public opinion and the renewable industry’s past development and implementation performance. Falling real equipment costs are also in favour of renewables, although land costs are high and installation costs have not fallen to the same extent as equipment costs.

However, the era of generous payments for renewable output under the Renewable Portfolio Standard looks set to be curtailed, and the government’s emphasis on wind rather than solar capacity additions, particularly offshore with its longer lead times, could slow the overall renewable programme, suggesting that the 2036 target could be on the ambitious side.

As a result, the cliff edge apparently beckoning South Korean LNG may prove to be less of a threat than the 10th plan might suggest.

That said, demand for LNG from the electricity generation sector is likely to fall in the near term as a result of the weak economy and growth in coal and nuclear output. According to KEEI data, contraction had already begun in 2022, with the amount of gas used for power generation falling to 18.3mn mt in the first ten months of the year from 19.4mn mt in the same period of 2021. The KEEI anticipates that as a result overall gas use will fall to 44.1mn mt in 2023.

But beyond 2023 and possibly 2024, recovery in LNG demand is anticipated in the second half of the current decade and into the next. The consultancy Rystad Energy, for instance – after an assessment of the 10th Basic Plan – projects that South Korean LNG demand will still rise to 51mn mt in 2030 and 54mn mt in 2040.