[NGW Magazine] Mastery of the Arctic

The undecided legal possession of the Arctic means that different countries are able to assert their rights to it with little fear of redress. So far Russia is making most of the running in terms of business deals, while Norway is busy issuing licences.

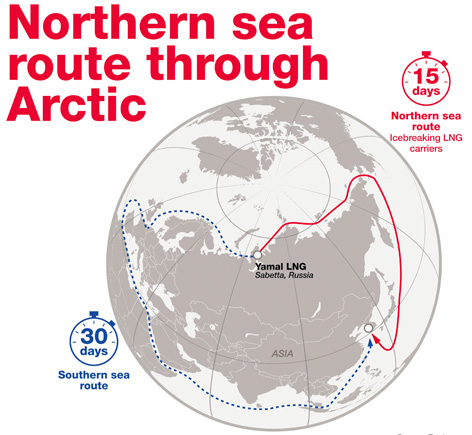

Advances in liquefaction technology and prospects of opening up much shorter transport routes that link North America and Eurasia have enhanced the prospects of Arctic gas exploration and production. The 40% shorter distance, compared with the Suez or Panama canals, still faces problems in winter but global warming could even solve that problem too by 2040. As a result, the Arctic has become a strategic region for governments and the gas industry but views on how to manage it range from militarisation to regional co-operation and trade.

Norway, Canada, US, Russia, Denmark (Greenland) and Iceland want sovereignty over Arctic areas and hence exclusive rights to its resources and some have applied to the United Nations’ Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). However the status of the Arctic is undefined in international law, with some bodies arguing that it should remain a no-man’s land. Iceland claimed its right to the Aegir Basin area and the western and southern parts of Reykjanes Ridge (2009).

Denmark has filed five submissions, and these were made in respect of the north of the Faroe Islands (2009), the Faroe-Rockall Plateau Region (2010), as well as the Northern (2014), North-Eastern (2013) and Southern Continental Shelf of Greenland (2012).

The Norwegian submission covered the North East Atlantic and the Arctic (2006) - some of these claims were regulated independently by Norway and Russia in the Treaty concerning Maritime Delimitation and Co-operation in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean in 2010. Although the treaty is unique in the Arctic context, it does omit a sensitive topic, namely future gas and oil exploration and production around the Svalbard archipelago.

Canada has so far only made one submission, in respect of the Atlantic Ocean (2013). However, it is expected to file its second, the so-called “North Pole” final submission, concerning the Lomonosov and Alpha-Mendeleev Ridges somewhere in 2018. Russia’s submission of 2015 is under review by the CLCS which met February 12-23 this year and its decision will have a substantial impact on Arctic exploration and the shape of future transportation routes in the far north.

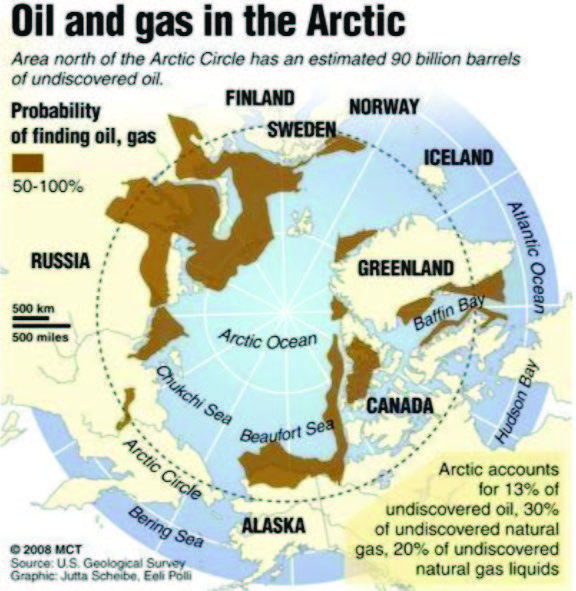

Countries with no Arctic territory are also keen to have a say in its future: China, Japan and the South Korea are interested in transportation routes and energy resources. And the EU presented an integrated European Union policy for the Arctic in April 2016 and appointed its first ambassador at large for Arctic Affairs, Marie-Anne Coninsx, then the EU ambassador to Canada. The keen interest for this region is well understandable: there is a lot at stake above latitude 66°30' N.

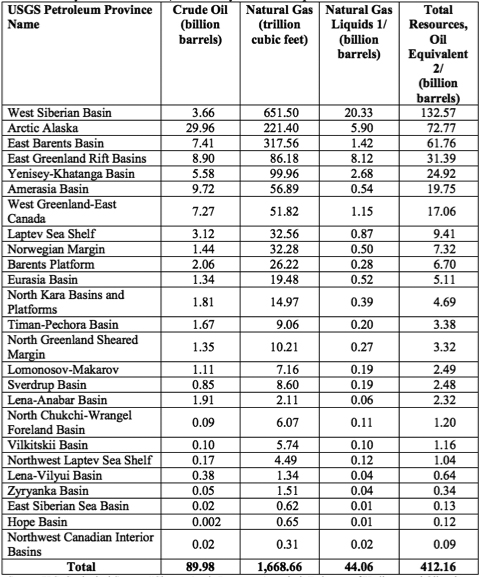

The gas deposits in the Arctic are abundant and account for about 22-30% of the world’s undiscovered natural gas resources.

Arctic Mean Estimated Undiscovered Technically Recoverable, Conventional Oil and Natural Gas Resources

U.S. Energy Information Administration

The Arctic Ocean covers 14mn km² and is mostly less than 500 metres deep. Digital technology for seismic and other prospecting methods is moving forward, saving time in both exploitation and remediation if things should go wrong.

However, environmentalists have put forward radical arguments for a total ban of Arctic exploration for oil and gas, arguing for example that it is incompatible with the Paris Agreement of 2016. These claims have yet to be tested in the courts.

For the gas industry the signal is clear however: corporate directives and social responsibility strategies should improve the overall standardisation and harmonisation of technical and operational business practices in areas such as health, environment and safety. Transparency and exchange of the best practices in these areas between enterprises is therefore advisable.

As for today, it is fair to say that Arctic, covering an area of roughly 20mn km², remains an unsolved puzzle and poses a challenge in political, economic and environmental terms, as Norway demonstrates.

Norway, known for its welfare policies, is an energy nation and a petroleum giant. Besides, Norway is a polar champion, with polar heroes – such as Fridtjof Nansen and Roald Amundsen – and also a well-established Arctic strategy thanks to the work of Stoltenberg’s two consecutive cabinets.

Their work has defined the northern regions as Norway's most important foreign policy area. Norwegians have long developed their competence in Arctic oil and gas exploration and parliament opened up parts of the Barents Sea as early as 1989.

On the other hand, most of the country’s electricity comes from hydropower: clean energy accounts for 69% of Norway’s total energy use. Its energy policy emphasises sustainable development and assigns Enova organisation a main responsibility for Norway’s conversion towards being a low-emission society.

And a previous prime minister, Gro Harlem Brundtland, chaired the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) and coined the concept of sustainable development - first introduced to the public in 1987 by WCDE’s report Our Common Future.

The minister of petroleum and energy, Terje Soviknes (Progress Party) replaced Tord Andre Lien at a time when environmental groups brought the case against the Norwegian government claiming that the king’s resolution of June 10, 2016, which permitted the 23rd round of licensing, violated section 112 of the constitution. Section 122 says that every person has the right to a clean and diverse environment and furthermore natural resources should be managed by comprehensive long-term considerations whereby this right will be safeguarded for future generations.

Credit: MCT

On January 4 this year, the Oslo District Court dismissed the case; but environmentalists were ready for that, announcing a month later their plans to appeal to the Supreme Court.

Also, in the 23rd round three licences in the northeastern part of the Barents Sea were awarded to Statoil and Cairn’s subsidiary Capricorn. Russia claimed this violated the Svalbard Treaty (1920) but Lien explained to the Russian government that Svalbard was a part of the Norwegian continental shelf and hence the awards were valid.

The 1920 Treaty of Svalbard recognises Norway’s sovereignty over the archipelago but gives all countries the right to exercise maritime, industrial, mining and commercial activity where the Norwegian rule of law applies.

American, Russian and Norwegian companies began drilling for oil and gas on Svalbard as long ago as 1960, the first commercial drilling taking place in Kongsfjorden (Kvadehuksletta 1962-1966). But it took until the late 1980s to find commercial gas on Svalbard.

Soon after, Russian Trust Arktikugol made a significant oil discovery in Billefjorden (1992). In 2004, Russia announced it would proceed with oil and gas exploration around the Svalbard-archipelago, and it remains determined to keep this promise.

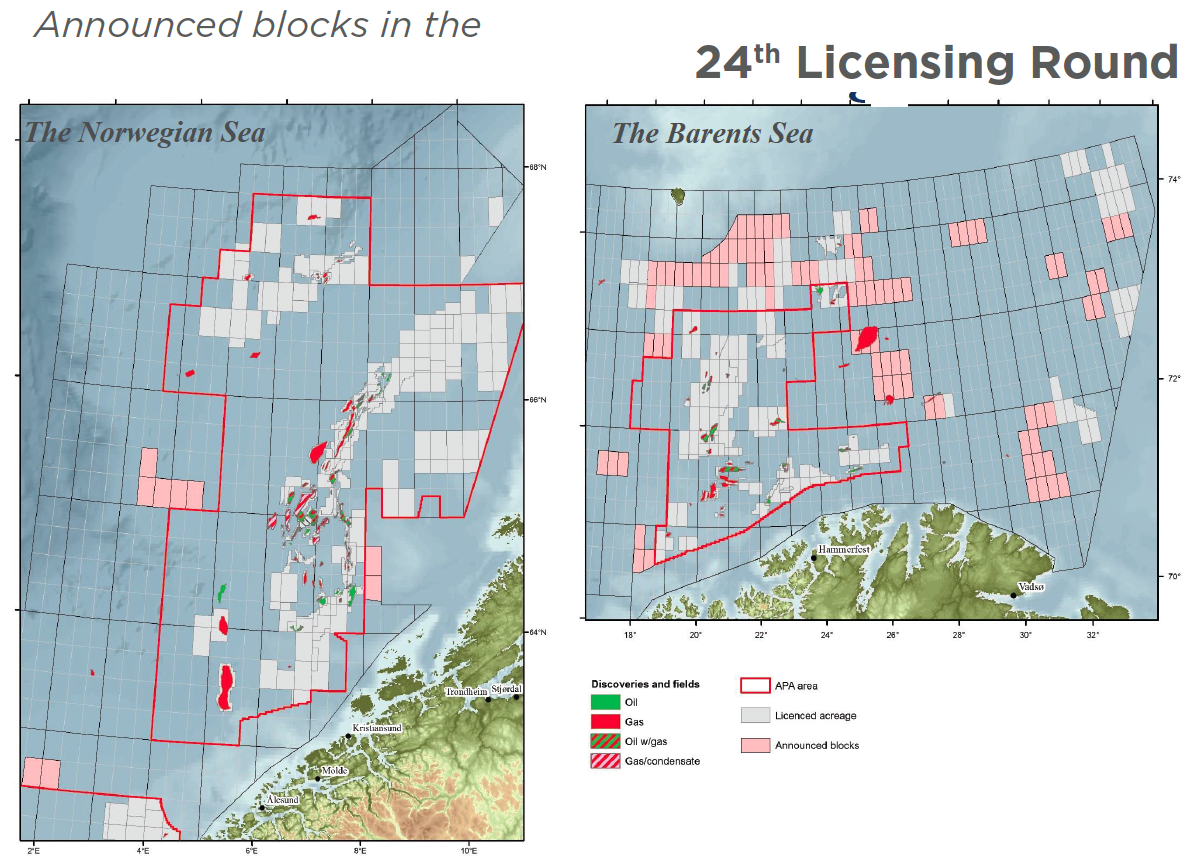

Credit: Government of Norway

On August 29, 2016, Norway invited companies to nominate blocks for the 24th licensing round in the frontier areas of the Norwegian Sea and the Barents Sea. In total, 11 companies took part: Anglo-Dutch Shell, AkerBP, UK Centrica Resources, Russian-owned DEA, Japanese Idemitsu Petroleum; Kuwaiti Kufpec, Swedish Lundin, Austrian OMV, RN Nordic Oil, Statoil Petroleum; and German Wintershall. On June 21, 2017, the 24th licensing round was announced, and 102 blocks were offered: 93 in the Barents Sea and 9 in the Norwegian Sea.

The 24th round’s awards are to be announced in the first half of 2018.

Soon after the 24th round was announced, on October 10, 2017, the parliamentary commissioner Une Aina Bastholm (The Green Party) submitted a proposal asking parliament to suspend the planned allocation of new exploration permits.

On February 15 the parliamentary committee on energy and environment issued an official response to this proposal. Most of the committee underlined the importance of the petroleum industry for Norway and proposed that the parliament ask the Norwegian government to submit a new petroleum report on Norwegian oil and gas policy – in view of the climate challenge and the new market situation.

In addition, the parliament was asked by the Green Party (GP) and the Socialist Left Party (SLP) to stop the APA awards as well.

Neither of the proposals were adopted. On February 27 this year, the parliament rejected the joint GP and SLP proposal as well as the Bastholm’s proposal by a vote of 93 to 8.

Recently, it was also proposed in the parliament to ask the Norwegian government to submit a new petroleum report on Norwegian oil and gas policy in view of climate challenges and the new market situation. The results of the parliament’s votes (52 to 48) that day were only marginally in favour of dismissing this proposal.

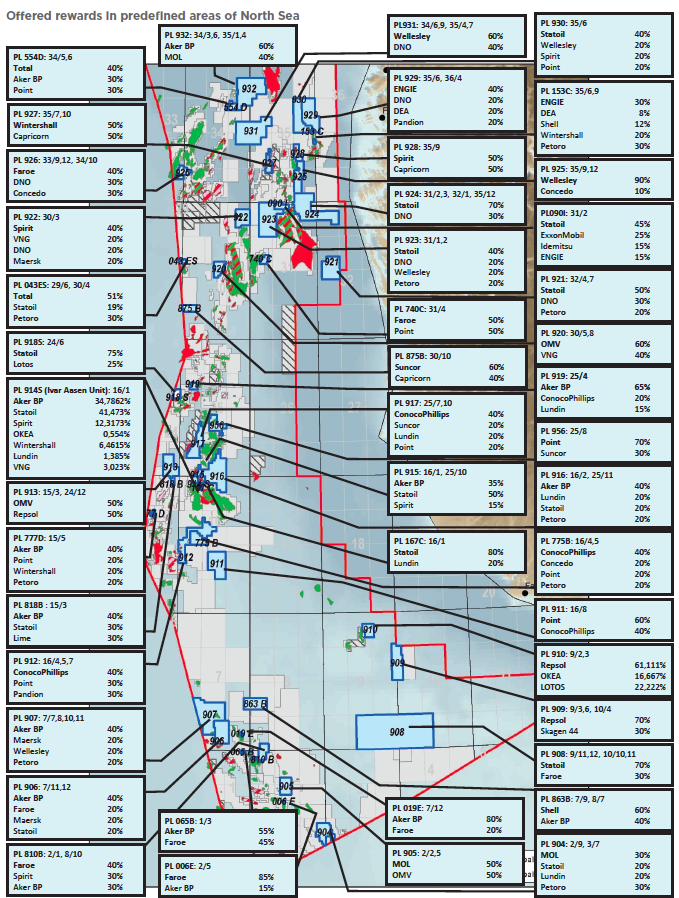

Credit: Norwegian Petroleum Directorate

The aim of the Norwegian government is clear. As Soviknes himself said at the Oslo Energy Forum February 10, “Gas is part of the solution – not the problem.” Norway will drill. And gas will be needed. This is especially true for the European Union where gas, known for its environmental benefits relative to other fossil fuels, has been identified as the main solution to the problem of oil, coal and carbon emissions.

Norway’s prime minster, Erna Solberg, said that allocating attractive exploration areas was a key element of Norway’s petroleum policy.

These intentions are also reflected in the recent Award in Pre-Defined Areas (APA 2017) licencing round. In mid-January the ministry awarded 75 exploration licences to 34 companies to carry out exploration work in Norwegian fields in mature areas of: the North Sea (45), the Norwegian Sea (22) and the Barents Sea (8). As such, the APA 2017 resulted in a record high number of awards, 19 more than the previous APA round in 2016.

So far however, the greatest records in the Arctic have been set by Russia. Aware that it accounts for half the Arctic population and owns more than a half of all the Arctic coastline, Moscow has taken the opportunities that arise in the High North with determination. President Vladimir Putin has kept the Arctic high on his political agenda. In 2014, the government issued its Principles of the Arctic State Policy of the Russian Federation to 2020 and Beyond.

Credit: Total

This country has the largest fleet of nuclear icebreakers in the world. One of them is even accessible to the public. For a fee of $28,000 an individual can take a 14-day cruise in the High North on board the 50 Let Pobedy – which dates the vessel’s naming ceremony to 1995, 50 years after Russia's victory in the Second World War. In August 2017, this icebreaker set a record for a voyage from Murmansk to the North Pole in just 79 hours. Also, last summer the Russian icebreaking LNG carrier Christophe de Margerie made its first transit through the Northern Sea Route. The vessel carried LNG from Snohvit offshore Norway to Boryeong in South Korea and delivered a cargo for Total Gas & Power. The Christophe de Margerie took 15 days, half the time a transit through Suez Canal would normally take.

It is perhaps not too early to say that while some Arctic fronts are forming, the centre of gravity of the global gas market is moving towards the Asian-Pacific region where the Arctic component plays a strong, if not a pivotal, role. However, the territorial claims to the Arctic can complicate the safety of the region until they are solved by agreements between the involved countries and with respect to the UN CLCS’ technical recommendations. The final shape of the Arctic is yet to be decided.

Paulina Landry