[NGW Magazine] Argentina and Chile: Compare and Contrast

Majors are becoming more interested in frontier gas exploration in the far south of Chile and Argentina but these remote regions still present a number of challenges for energy companies.

Argentina’s “vast underexplored frontier acreage will appeal to exploration-focused players,” energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie predicted in its report Latin America Upstream 2018, published in January.

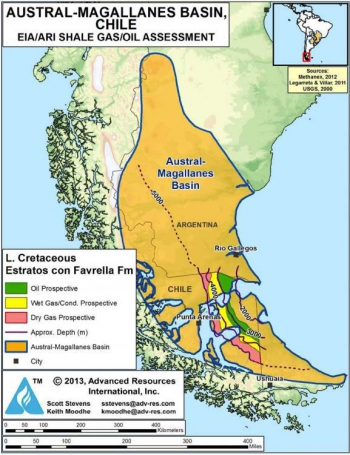

In particular, the Magallanes Basin – which is in the far south of Patagonia crossing the Chile-Argentina border – is attracting majors that are testing for tight gas in the region, Wood Mackenzie said. “The majors will look to complement their Vaca Muerta positions with offshore exposure,” the analysts added. The vast Vaca Muerta formation, in the Argentine province of Neuquen, is one of the largest shale deposits in the world.

Credit: EIA

Companies that include Chilean state producer Enap, US major ConocoPhillips, Argentina-based explorer Compania General de Combustibles, US independent GeoPark and Argentina’s state run oil firm YPF are all evaluating the economics of horizontal tight gas wells in frontier regions of Argentina and Chile.

The Chilean portion of the potentially shale-rich Magallanes basin – known in Argentina as the Austral Basin – holds an estimated 49 trillion ft³ of shale gas, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). Overall Chile has an estimated 55 trillion ft³ of technically recoverable shale reserves, but little unconventional production to date. Although most of the Magallanes Basin is found in Argentina, most activity to date has taken place on the Chilean side.

The Chilean portion of the basin, which is in the Tierra del Fuego region, started producing conventional natural gas more than 60 years ago and accounts for most of the country’s oil and gas output. Enap produces around 5,000 barrels/day from conventional reservoirs in the Magallanes Basin, and has begun exploring for tight gas.

Fell block, home of the Uaken 1 exploration well (Credit: GeoPark)

The firm has been planning since at least 2011 to also explore for shale gas in the region, and signed an agreement with ConocoPhillips to explore and potentially produce shale gas in the Magallanes in 2016.

Latin America-focused explorer GeoPark has been active for 15 years in the Fell Block, located in the Magallanes Basin near the border with Argentina, Alberto Matamoros, GeoPark’s Director for Argentina and Chile, said in an interview with NGW. In January, the company said it had completed drilling and testing of the Uaken 1 exploration well at Chile’s Fell block, which is 100% operated by the US-based independent.

The well, which was drilled to a total depth of 3,658 ft, has an average production rate of 0.8mn ft³/day of gas and is already in production, GeoPark said.

What is different about the Uaken 1 gas discovery is that it is a shallow well and that production is from El Salto formation, said Matamoros. That opens the door to both new prospects as well as some already drilled wells that have produced from other formations, he added. “These are low cost wells, just $1-1.5mn to drill, compared with the average of $3.5-$5mn for deeper wells,” he said.

The firm has a long-term contract to sell gas produced at the block to a Methanex methanol plant, which is about 100 km away. “This is an unusual market because GeoPark’s primary client is very close by and is already connected by pipeline,” said Matamoros. “Moreover, the methanol-producing client has excess capacity, so there is potential for additional demand. Thus, the prospect for additional production and sales are very good in Chile,” he added.

However he admitted that the extreme climate in the south of Chile does overall pose a challenge for operators; and so does not having full availability to service providers and drilling companies that thrive in other basins with more oil and gas activity.

"But the state-run company, Enap, has installed good infrastructure and the methanol gas client is very close by with a good pipeline, thus minimizing transport costs,” he said.

In addition, the business environment in Chile – one of the most attractive in Latin America – is an advantage, he said. “The rule of law is clear and respected, contract sanctity is established and transparent, and there are clear arbitration channels for dispute settlement,” he pointed out.

In addition, the royalty scheme for gas in Chile is “the most attractive in Latin America” at 3.5% flat royalty – and the corporate taxes are close to 20%," he added.

Over the border in Argentina, there are an estimated 802 trillion ft³ of shale gas reserves, which has drawn investor interest in recent years but mainly in central Argentina, at Vaca Muerta, rather than in the south.

Vaca Muerta (Credit: YPF)

However the challenges of operating in Argentina have also surfaced. Operations can be set back by inadequate infrastructure, lack of in-depth information about the subsoil, and trade union unrest, among other factors.

Development costs are also significantly higher than elsewhere – a shale well, for instance, can cost up to five times its equivalent in the US, putting pressure on project costs at a time when low oil prices have caused many energy firms to cut back.

The challenges faced at Vaca Muerta could deter companies from venturing into Argentina’s extreme south, at least in the short-term. Once infrastructure and other issues are resolved at Vaca Muerta however, companies may have more confidence to venture into frontier regions.

If the operating environment continues to get easier in southern Chile through infrastructure improvements and greater access to service providers and drillers, then majors may gravitate south to join GeoPark and others already operating there, or venture into less-explored frontier regions. Given the remoteness and climate challenges of the region, progress is likely but may take some time.

Sophie Davies