[NGW Magazine] Gazprom Goes for Directness

Gazprom has to guarantee firm gas deliveries to its customers, or the value of its gas goes down; not everyone however sees its direct pipelines to market in the same, benign light.

The size of Gazprom’s exports to Turkey – 29bn m³ last year – reveal the value of TurkStream to Gazprom: together with Blue Stream it would allow Gazprom to meet its existing export sales to Turkey without reliance on any transit states: Ukraine, Romania, and Bulgaria. The project has some developments: on May 26, Gazprom signed a protocol with the Turkish government on the Turkish onshore section of Turk Stream governing the terms and conditions of the construction work. The press release did not specify the route or final destination but the Gazprom Export website indicates that the onshore Turkish section will run to Ipsala, on the Turkey-Greece border.

The route choice and plan goes beyond Turkey to another important market: Italy. Its size explains the company’s enthusiasm for gas deliveries to Italy via the second line of TurkStream and the proposed ‘Poseidon’ pipeline from Greece to Italy, which would reduce Gazprom’s dependence on gas transit via Ukraine when delivering gas to Italy. The agreement, signed in June 2017 by Gazprom, Edison, and Greek Depa, aims to establish a route for Russian gas exports to Italy via Turkey and Greece. A key element is the proposed Poseidon pipeline, under the Adriatic Sea from Greece to Italy. The Poseidon project is a parity JV between Depa and Edison.

While the first line of TurkStream is intended to supply the Turkish market, the second line is planned to supply customers in southeastern Europe. It is this desire to use TurkStream to supply customers beyond Turkey that makes the co-ordination of the Turkish onshore section of the project and the extension, both through the Greek transmission system and the Poseidon pipeline, so important for Gazprom as a gas supplier, and for the Turkish government, which seeks to generate transit revenues and increase its political importance to the EU. Some gas – up to 5bn m³/yr – will also flow through projected Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria, owned by Bulgarian Energy Holding (50%) and IGI Poseidon (50-50 Depa and Edison).

Huge demand in north-western Europe underlies NS2 push

The fact that declining Dutch gas production is leading to a rise in Dutch imports of Russian gas, together with the size of Gazprom’s exports to other countries in north-western Europe (Germany, France, and the UK), highlights the importance of NS2, from Gazprom’s perspective.

While European commentators speak of diversification being essential for security of supply, Gazprom is concerned for security of demand and transit, and has used this to argue for transitioning away from Ukraine in favour of NS2 for their important northwestern customers. Furthering the potential uses of NS2, the Eugal pipeline has been proposed as an onshore complement to NS2, to bring gas from the German Baltic coast to the German-Czech border, for onward delivery via the Czech system to the Baumgarten gas hub in Austria. The idea is to meet both the substantial growth in Austrian imports of Russian gas, and to offer an alternative route for Russian gas deliveries to Italy.

Gazprom Export highlights need for NS2

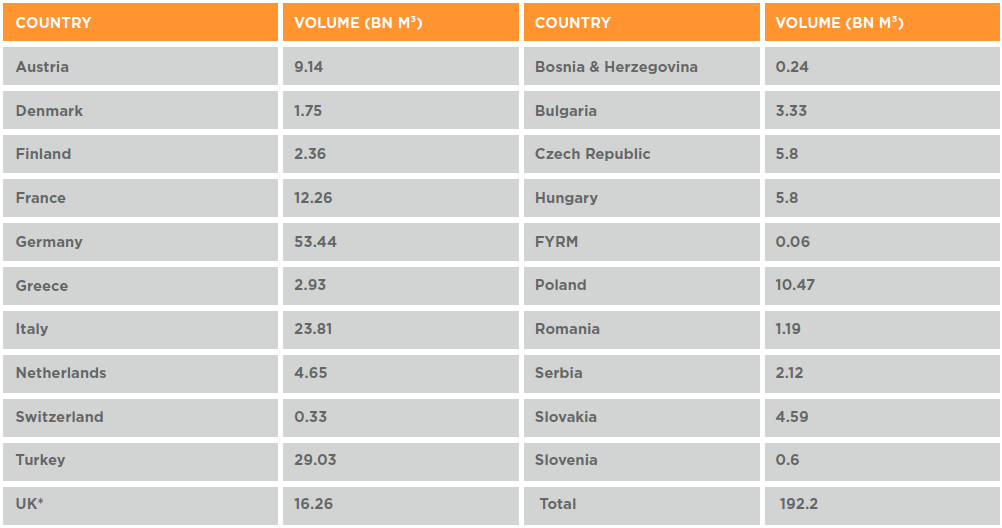

Gazprom Export has published a breakdown of its gas sales by destination in the calendar year 2017, when total sales to ‘Europe’ reached 192.2bn Russian m³ (see below). The breakdown includes 16 EU member states, plus Switzerland, Turkey, and three non-EU countries in southeastern Europe: Bosnia & Herzegovina, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Serbia. Gazprom excludes Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania from its definition of ‘Europe’, and instead groups them with its exports to the former Soviet Union (FSU).

Gazprom’s three largest markets – Germany (53.44bn m³/yr), Turkey (29.03bn m³), and Italy (23.81bn m³) – accounted for 55% of Gazprom’s total European sales (106.28bn m³). When the UK (16.26bn m³) and France (12.26bn m³) are added to the list, sales to the five largest markets accounted for 70.1% (134.8bn m³) of Gazprom’s European sales in 2017. A full listing of these ‘European’ gas sales numbers is provided in the table.

Gazprom Export European gas sales by destination in 2017

* This may include GM&T deals done in UK but for delivery elsewhere (Editor) | Credit: Gazprom Export)

Close observers may note differences in the figures reported here and in other sources, owing to different standards of measurement. If the various conversion factors (discussed below) are applied to Gazprom’s exports in 2017, the total sales to Europe of 192.2bn m³ reported by Gazprom would fall to 183.75bn m³. This still leaves Gazprom by far the largest supplier of natural gas to the European market, but is worth analysing.

While natural gas is often reported by volume (in cubic metres in Europe, or cubic feet in North America), what really matters is the energy content of that gas. This varies according the geographical location of where the gas was produced, meaning the quality of the gas even in one system, such as the UK, is not constant. As the UK natural gas transmission system operator (TSO), National Grid, notes:

Calorific value (CV) is a measure of heating power and is dependent upon the composition of the gas. The CV refers to the amount of energy released when a known volume of gas is completely combusted under specified conditions. The CV of gas, which is dry, gross and measured at standard conditions of temperature (15°C) and pressure (1013.25 millibars), is usually quoted in megajoules/metre³ (MJ/m³).

While natural gas is mostly methane (87-97%), it contains other components, such as ethane, propane, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide, in varying proportions. Therefore, one cubic metre of natural gas from one source may have a slightly higher or lower energy content than a cubic metre of natural gas from another source, because it has a different chemical composition. This variation is illustrated by the CV. The second point follows on from the first. The quote from National Grid above refers to the measurement of natural gas under ‘Standard conditions’, at 15°C under normal atmospheric pressure. However, some sources measure gas under ‘Normal conditions’, at 0°C under normal atmospheric pressure. Because natural gas expands as the temperature rises, one cubic metre of natural gas at 0°C expands to 1.055 cubic metres at 15°C whilst retaining the same energy content, or CV.

For example, in Europe, the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (Entsog) publishes its data in normal cubic metres (i.e. measured at 0°C), while the EU statistical agency, Eurostat, the International Energy Agency (IEA), and BP (Statistical Review of World Energy), all publish their data in standard cubic metres (i.e. measured at 15°C). So too does Norway's offshore regulator, the petroleum directorate.

To complicate matters further, the data published by Gazprom are expressed in Russian standard cubic metres, which are measured at 20°C under normal atmospheric pressure. Therefore, every such unit has a slightly lower calorific value than its counterpart, the European standard cubic metre. To account for this change, it is necessary to multiply every Russian standard cubic metre by a factor of 0.983. The key conclusion here is that the combination of the calorific value of the gas and the temperature under which the gas is measured means that data from different sources are not directly comparable. Therefore, the figures reported by Gazprom Export will not match up with the figures reported by Entsog in their statistical charts, nor with the data published by Eurostat, the IEA, or BP.

Ben McPherson, Jack Sharples