[NGW Magazine] Russia creates gas demand

Gazprom, as an agent of Russian government, is uniquely placed to develop new demand for its gas as a transport fuel. Other companies will compete if the regulatory conditions improve.

Russia’s first small-scale gas liquefaction (SSLNG) projects were built in the Moscow and Leningrad oblasts in the early 1990s but there is a lot of room still for these to expand, given a favourable political and regulatory tailwind. Now overlooked by policy-makers and regulators, SSLNG could play a role in the country’s energy security and transport strategy.

Key to realizing this ambition is close co-operation between business entities and the government: the latter can influence market potential by regulations supporting demand, setting rates, taxes, concessions and so on. This is crucial for SSLNG players because if the government supports SSLNG, it could bring about a revolution in the Russian gas sector.

This co-operation is all the more important since the future of SSLNG is based mainly on the successful implementation of the government’s environment policies. A concerted approach to cutting the emissions of greenhouse gases, particulates and noise will benefit gas by penalising fuels that now are almost universally used in bunkering, urban transport and heavy goods vehicles.

Gazprom Export’s head of LNG Igor Mainitsky suggests that Russia has not given sufficient attention to LNG, emphasising instead the importance of electric and hybrid engines. He says this approach will slow down the development of LNG as a transport fuel. Statistics back this opinion up, by a quick comparison with the take-up of LNG heavy goods vehicles in other regions: China has 240,000; the US, 5,000; and Europe just 1,500.

The current forecast made by one division of Gazprom, Gazomotornoye Toplivo (GT), envisages that in 2030, there will be 63,000 heavy trucks in Russia. However, as the European experience shows, this forecast must be treated with caution. And given the lack of clarity on the government’s view on supporting SSLNG, it is unsurprising that only the state-owned Gazprom and its affiliates have entered this sector.

In Russia there are seven SSLNG sites, producing in total 100,000 metric tons (mt)/yr of LNG. There are many obstacles that this sector has to overcome, such as the lack of LNG dedicated infrastructure, or an agency whose job it is to develop LNG for transport and the lack of any definitive specific legal or regulatory framework.

Another difficulty is the heavy cost of technology, especially given that almost all the projects have been based on a range of models. Finally, the network of service centres for maintenance of vehicles using LNG is not well developed and not many vehicles are made that run on LNG. For example, the Russian truck manufacturer Kamaz said in May 2017 that it would manufacture trucks with LNG engines; but these vehicles were intended for Gazprom, which collaborated in their construction.

These limitations slow down the development of this segment, but it nevertheless has prospects because of the role that it may play in diversification of the possible uses of gas. In Russia, the target market is heavy trucks with a carrying capacity of more than 12 mt; intercity buses; city buses; maritime transport; heavy equipment with a carrying capacity of more than 90 mt; tractors; and gas turbine locomotives.

The deputy director-general of Gazprom GT, Vyacheslav Khakhalkin, sees advantages for LNG as it allows a 65% reduction of harmful emissions into the atmosphere compared with other fuels; engine life expectancy is 1.5 times longer; and there is the possibility of transporting LNG to regions far from the high-pressure grid. In addition there is still discussion about the most effective locations for SSLNG.

According to Gazprom GT analyses, distant regions will constitute only 7% of the SSLNG market, but seven priority clusters will constitute 90% of SSLNG market.

Seven priority clusters for SSLNG projects in Russia

Source: Gazprom

Gazprom GT has half the SSLNG market and is the most ambitious company in Russia’s LNG transport fuel sector, aiming to produce 668.5 mt/h of LNG by 2032.

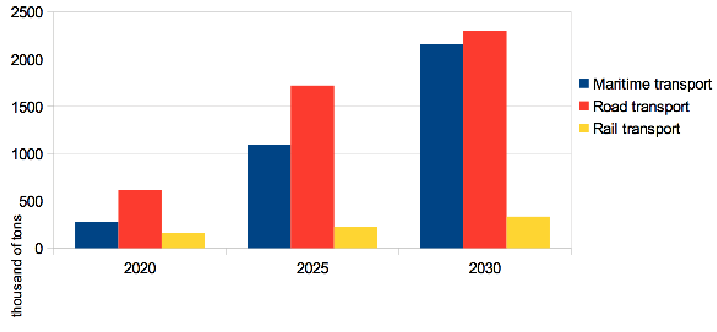

Potential demand for LNG as a motor fuel in Russia 2020-2030

Source: Gazprom Gazomotornoye Toplivo

One reason is the shortage of infrastructure. But there are other companies that are also planning to enter the SSLNG market.

In the Baikal region alone there are numerous companies such as Kada Neftegaz, Irkutsk Oil Company, Petromir, Bratskekogas and Yatek. There are however many difficulties from the political side, as the experience of the Baikal region shows: decisions by governors can trump project economics. This is also an argument for the creation of a government agency connecting business with regional administration, which could save SSLNG projects from such adverse decisions.

Gazprom GT is also planning to build an innovative passenger ship running on LNG on the Volga and Kama rivers in the Republic of Tatarstan: this will be the first example of LNG used in inland navigation in Russia. And some companies are more nimble than Gazprom, such as Zelenodolsk Gorky.

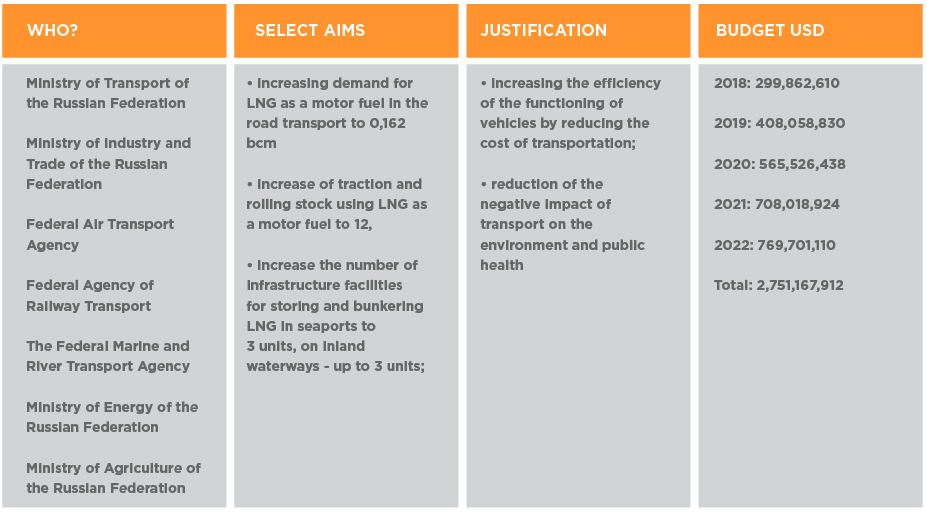

Government programme: Expanding the use of natural gas as a motor fuel for transport and special-purpose vehicles 2018-2022

Source: Ministry of Transport of the Russian Federation

CEO Renat Mistakhov has claimed that his company could build a vessel running on LNG within 17 months. The company has already developed a few conceptual LNG ships projects with a range of 400 km and capacity for 142 passengers. This is part of the government’s programme “Expanding the use of natural gas as a motor fuel for transport and special-purpose vehicles”

Experimental bunkering infrastructure for inland navigation will be built in Tatarstan and for maritime transport in the Baltic region, starting this year, but it will take some time to assess its progress, the more so as the Baikal region has demonstrated that regional policies can have a bigger influence on SSLNG projects than economic factors.

SSLNG is also under-used in the power sector, partly owing to a small price difference between LNG and other fuels, but the government could stimulate the market through regulation.

In the Baltic region a privately-owned Russian company “LNG Gorskaya” is building a project which will produce 1.26mn mt of LNG for delivery to buyers in Europe and bunker vessels in the Gulf of Finland, using a stationary barge.

The first phase of 0.43mn mt/year was due to be complete in 2017, the second in 2019 and the third in 2021, and it could come to market ahead of Gazprom’s much larger Baltic LNG project. But there is still no information about the progress of this project.

A part of the company’s strategy is to invest in LNG infrastructure in other Baltic and North Sea countries, in the first place in Germany, Finland and Sweden.

Baltic LNG has been scheduled for 2022-2023. The expected annual production is 10mn mt/y of LNG. The first deadline was 2021 but for reasons of documentation, the deadline has been postponed.

In September 2017, Gazprom’s Alexander Medvedev told a Sakhalin oil and gas conference that the pre-front-end engineering and design of the project had been done, and that Gazprom and Shell will set up a project company to build the project in the middle of this year.

These projects are seen as competitors to Lithuanian and Polish plans to develop their own projects in the Baltic region. The Polish Institute of International Affairs has been warning since May that Russian companies will invest in LNG projects that will affect their own business models – a bigger threat, apparently, than the political risk posed to security of energy supply.

This is a new situation, especially in the context of Nord Stream II: Russian SSLNG projects in the Baltic region could circumvent Western sanctions and will quietly increase Russia’s share in the European gas market.

In Poland, where Russian companies such as Gazprom Germania, Vemex, Novatek and Cryogas M&T are among the main players in the SSLNG sector, there is no serious opposition to Russian SSLNG activity, suggesting that this might be a good direction to increase the share in the European gas market.

Gazprom is also planning the resuscitation of the Vladivostok LNG project, again using SSLNG. In September, at the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok Gazprom signed an agreement with Japanese Mitsui which confirms their commitment to collaborate in the production, transport and marketing of small- and mid-scale LNG in Japan, as well as in LNG bunkering in the Sea of Japan.

Another new and innovative project is the mobile LNG production and sale complex (Cryoblock) with output capacity of 0.6 mt/hour. Cryoblock is designed and will be built by a company specializing in innovations in the gas producing NPK-NTL. Cryoblock will operate at first in the Moscow Gas Refinery Plant which is from 2014 owned by Gazprom GT.

Additionally in the first quarter of 2018 the first mini LNG plant in Sakhalin will start operating with production of 12,000 mt/yr of LNG, and a second by the year end, with the same output.

The project is financed by Sakhalin Oblast Development Corporation (SODC), independent investors and CNG and LNG production company PSK Sakhalinwhich owns the project. The budget is estimated at roubles 824mn, of which the SODC will contribute roubles 701mn and PSK Sakhalin roubles 123mn.

Another new project is Novodvinsk LNG which is supposed to be realised by the company Oboronlogistika and will produce 13,000 mt/year in the first stage and ultimately 200,000 mt/yr.

Gazprombank affiliate Cryogas is planning to build a 660,000 mt/yr SSLNG complex in the Leningrad Oblast but there is still a discussion about the site.

Originally, it was supposed to be at Vysotsk, but now the company is thinking about Ust-Luga or Primorsk. Cryogas plans to start the construction in the end of 2017 or in the first months of 2018 and the work will take three years. Novatek has 51% of this project.

It is not Cryogas’ first SSLNG project. There is one already operating in Pskov Oblast (21,000 mt/yr) and another in Kingisepp city (7,000 mt/yr) which supplies mainly the northwestm of Russia. There is also another one still in preparation in Karelia, which should produce 55,000 mt/yr of LNG in the first version or 155,000 mt/yr in the second. The implementation date is 2017-2019 but construction has been slowed down by a lack of potential customers.

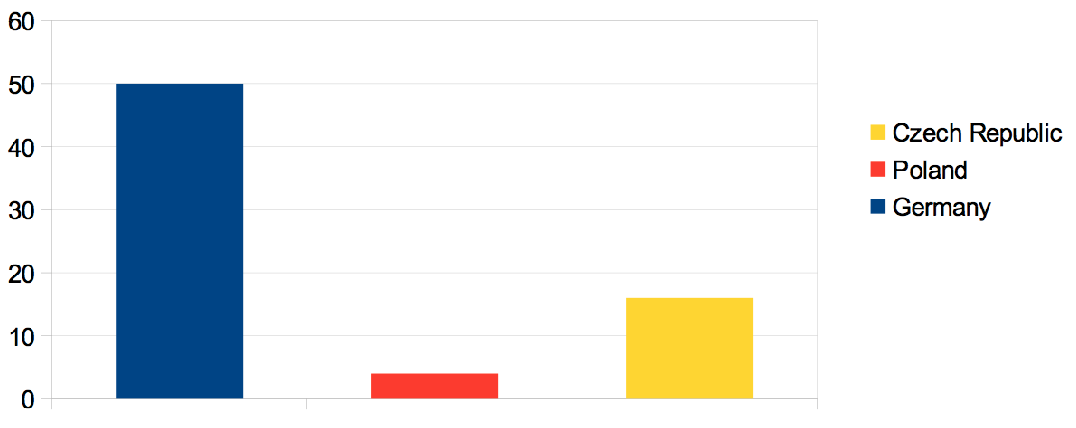

Number of Gazprom/Vemex CNG/LNG stations in Germany, Czech Republic and Poland

Number of CNG/LNG Stations: Germany = 885 | Czech Republic = 143 | Poland 28 (Source: PISM)

SSLNG has the potential to be the first step to make a small revolution in the Russian gas sector but it needs a grassroots work.

SSLNG has arguments to be interesting for all players but the biggest risk is the fact that the demand for SSLNG will not rapidly increase without adequate infrastructure, while distribution infrastructure will not be built without adequate demand.

To ensure the growth of SSLNG in Russia there has to be SSLNG dedicated infrastructure simultaneously with the appropriate regulations to enforce demand.

The government’s draft document, Expanding the use of natural gas as a motor fuel for transport and special-purpose vehicles, is a start, and it covers also CNG. But so far there is no independent programme to force SSLNG businesses and the regulatory and policy makers to work together.

As for the infrastructure, the only entity with the ability and means to take a risk in this is the government. It regulates the gas market and controls the most active company in this sector – Gazprom.

It can therefore bring pressure to bear on administrations in regions that could invest in SSLNG projects. But even Gazprom in its analyses assumes that private business will not enter this sector until 2021 because it will take that long for the infrastructure to be built.

Kamil Sobczak