[NGW Magazine] China and the US option

China’s plans to import gas from the US might not spell the end of Russia’s own ambitions but they do add urgency to its infrastructure projects and foreshadow a change in the three-way relationship.

In the late Soviet era, gas delivery emerged as one of the most important of the Kremlin’s endeavours and this became even more obvious with the arrival of Vladimir Putin as president. Gas became not just the only way to bring in the essential revenues – Russia had little else to send to the global market besides possibly weapons – but also a tool in the geopolitical game.

And here, Europe was the chosen bride. It was not just a pragmatic consideration – the very fact that Europe is a huge gas market – the reason for the attraction was much deeper. Indeed, despite all bickering with what the former US secretary of state Donald Rumsfeld called “old Europe,” the Russian elite craved recognition by the European order, either directly or indirectly.

It is European cities that are the Russians’ major tourist destinations. It is there that they buy real estate and send their children to study. Geopolitics, not just purely economic, interests have conditioned Russia’s approach to Europe. Consequently, the Putin regime continued to regard Europe as the major market for Russian gas, and here, of course, the Kremlin relied on the web of gas lines, many of which had been laid down during the Soviet era.

Anxious to find common ground with the West and especially Europe, the Kremlin had accepted its seemingly inevitable geopolitical marginalisation until 2008, the time of the war with Georgia, when relations cooled. They cooled even faster in 2014, when the Ukrainian crisis erupted. This major political difficulty did not however lead the Kremlin to abort its plan to increase gas delivery to Europe, mostly Germany; and here, the Kremlin relied, reasonably enough, on the conflict between Berlin and Brussels and, of course, between Berlin and Washington. It was the reason why the Kremlin continued to lobby for Nord Stream 2 (NS 2).

Still, the conflict in Ukraine did lead the Kremlin to change its emphasis, or at least regard the Asian direction as important as the European, with China emerging as the potential replacement for the European market. It is true that Moscow and Beijing had been engaged in negotiations for years, but Beijing was not prepared to pay what Russia wanted and the negotiations went nowhere.

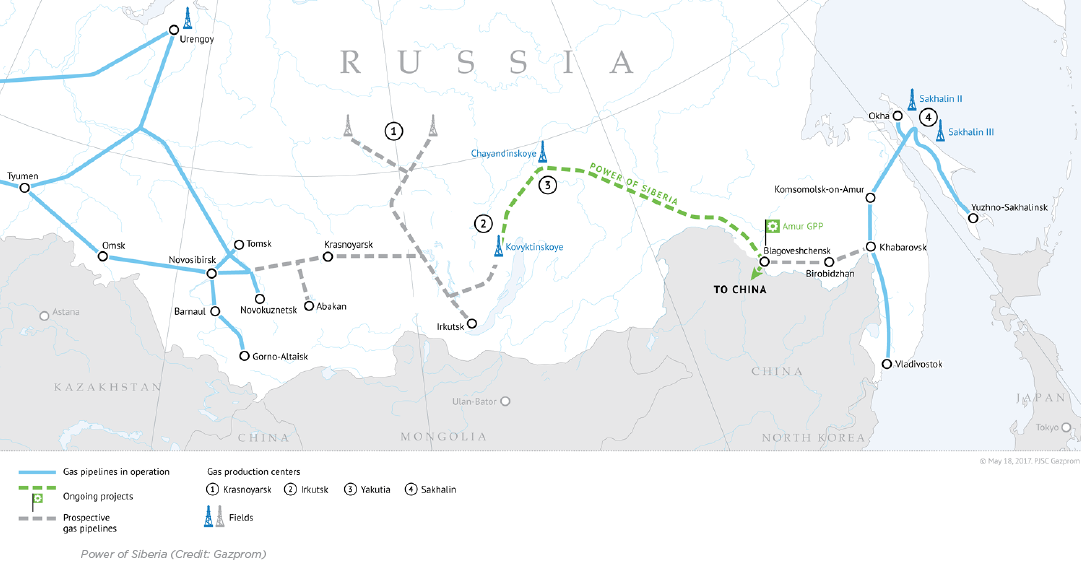

By 2014, the Kremlin had apparently made major concessions, and launched a major project – the Power of Siberia pipeline. Since NS 2 was not proceeding as smoothly as the Kremlin had planned, it planned to supplement Power of Siberia with additional projects, such as Power of Siberia 2 (also known as the Western route). But China’s new move could create a problem for Russia, exerting pressure on Russia’s other projects related to China and gas.

China’s rationale

China’s desire to be engaged in Power of Siberia and similar projects was not a purely economic exercise. In contrast to Russia and, even more, the US, where the mood of the electorate changes rapidly and most politicians have a two- to four-year attention span related to the electoral cycle, China’s totalitarian elite can plan for a decade or more.

In any case, Beijing can wait; plainly, because time works for it. Geopolitical equations are clearly present in Beijing’s economic plans. The gas line from Russia would solve several problems. The most important here is to ensure the flow of gas from other friendly continental powers, out of reach of US fleets.

Beijing is fully aware that a US invasion of Russia to cut gas lines is out of the question. As a matter of fact, Washington could not even handle the tiny but nuclear North Korea.

Russia’s connection also would help China to promote China’s grand project – Belt and Road – which should ensure in the long run China’s economic and geopolitical predominance in Eurasia and the world.

While still regarding Power of Siberia as an important enterprise, Beijing does not want to limit its activities in the gas realm, and this was the reason why it clinched the deal during Xi Jinping’s meeting with Trump. The plan involves an LNG plant in Alaska, with China as a major market.

What was the reason for this plan? Some observers, especially those hostile to Russia, saw the American/Chinese plan as a true catastrophe for Russia. For example, a Ukrainian observer noted that the agreement signalled to Russia that China does not need Russian gas and is not going to finance the project in any way. At the same time, Russia cannot afford to build Power of Siberia on its own.

In addition, the observer noted, any German politicians who are still infatuated with NS 2, would come to their senses, and a bankrupt and isolated Russia would have no choice but to beg Ukraine to permit it to use its territory and gas lines to send gas to the West. This is, of course, an exaggeration, and Power of Siberia most likely will proceed. Still, it would be wrong to assume that China’s relationship with the US will have no implications for Russian projects.

Playing with two ‘barbarians’

While China’s engagement with Russia has not just an economic, but also a geopolitical, rationale, the same could be said about Beijing’s relationship with Washington. Indeed, one could assume that China’s desire for American LNG is not due to purely economic reasons and, similar to Power of Siberia, has geopolitical implications.

It is true that time works for China: in a few years or a decade or so, it will tower over the US, in economic might. No statistical gimmicks will mask the actual decline of the US, whose plains, as president Donald Trump noted in his inaugural address, are covered by the hulks of closed factories like “tombstones.”

President Donald Trump with President Xi Jinping (Credit: The White House (CC BY 3.0 US)

By that time, China will be self-sufficient in high tech and a few years or decades after that it will have a military that the US will not dare to tackle. As a matter of fact, the experience with North Korea demonstrated clearly that even limited nuclear arsenals and a rudimentary nuclear navy – North Korea is engaged in building a nuclear submarine – is enough to preclude the “pre-emptive” wars in Serbian, Iraqi or Afghan fashion.

Still, China needs time and so it has to appease the “barbarians.” And this was the reason why Beijing tried to demonstrate to Trump that it accepted, in general, the notion of trade/economic equity and was ready to buy American goods, including gas.

One might state here that Beijing’s stress on purchasing American gas is neatly calculated. Those who watch American politics could see that the trade imbalance is regarded as the source of the US economic predicament. It was the battle cry of Trump as candidate for the presidency.

However, blaming outsiders for the poor state of the US economy is not good enough: Washington has provided a very limited menu of American goods for foreign consumers.

The trend actually started a long time ago. In the beginning, the deficit was explained by the fact that foreigners – and the Chinese increasingly became the major culprits – stole American technology, know-how, and other forms of intellectual property.

As time progressed, these accusations became rarer as China – and this was acknowledged by US observers – increasingly developed its own high tech.

There was also the proposition that the Chinese did not buy enough US agricultural products, a claim that has lapsed as it has become clear that these exports could not solve the problem of the trade deficit. And while the numbers of proposed goods declined, natural gas emerged as a saviour.

With the development of new technology, gas could be extracted from many new gas fields, many of them in the US. The news excited Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, who assured the electorate that this would ensure the US economic vitality. There were several arguments.

First, it was proclaimed that the US would have a cheap source of energy; actually, the US would have the cheapest energy among all industrial nations.

Consequently, foreign capital would return to the US, investments making the country “great again,” to use Trump’s expression, at least as industrial power. This was, of course, an illusion, and even Trump did not raise this proposition.

The second assumption – and it also emerged during Obama’s presidency – was that not only would the US be energy-self-sufficient, but that LNG could make the US an “energy super-power.” It could be a new Saudi Arabia, and these arrangements would replace the necessity for reviving or reanimating industry.

One might add here that Obama’s reasoning was quite similar to that of his counterparts in the Kremlin, who believed that Russia is an “energy superpower” and thus they need not pay much attention to the development of the country’s industrial base.

These delusions about easy fixes, widespread among a considerable segment of both the elite and the masses – have been perpetuated during Trump’s presidency. Consequently, Trump became quite aggressive in advertising American LNG. He – and of course a considerable number of US elite – proclaimed that Europe did not need Russian gas at all, and all of its needs could be well satisfied by LNG, mostly, of course, provided by the US.

Some eastern European countries, especially those with a strong dislike/suspicion of both Berlin and Moscow, apparently subscribed to this idea. China understood well the importance of LNG in Trump’s programme and this was one of the major reasons why Chinese proposed the Alaskan LNG enterprise to be built to provide China with LNG.

The deal demonstrates to Trump that he was absolutely right in seeing LNG as the silver bullet: massive selling of LNG would solve the problem of the trade deficit, and no dramatic changes in the Beijing/Washington relationship is needed. At the same time Beijing can buy more precious time, until it is strong enough to look Washington straight in the eye.

The proposition was not so much an economic as a geopolitical, gesture. Precisely because the enterprise is mostly political/geopolitical in nature, it is unlikely that it will spell the end of Power of Siberia, as some observers hope. Still, China’s actions would have had implications for Russia’s gas plans.

Implications for Russia

China’s engagement with the US, which is seen by most of the Russian elite as their clear geopolitical enemy, disturbs Russia. Even more, its apprehension was reinforced by the feeling that China is not as dependent on Russian gas as the Kremlin believed. Indeed, China had no interest in Power of Siberia 2 and other similar projects.

Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller responded to China’s actions by saying that China overestimated its ability to get enough gas outside Russia: by rejecting the additional gas lines from Russia, it risked a gas shortage.

At the same time, Russian officials assured China that Russia would finish Power of Siberia on time. In addition, Russia started to search for alternative customers for gas, such as Japan.

Dmitri Shlapentokh

.png_f1920x300q80.jpg)