[NGW Magazine] Netherlands: fast forward to a climate leader

In 2016 it was 27 out of 28 European Union countries in terms of the share of renewable energy in its energy mix, barely ahead of Luxemburg and behind Malta. It was also 20 out of 28 in the Climate Change Performance Index results for 2018.

In 2016 it was 27 out of 28 European Union countries in terms of the share of renewable energy in its energy mix, barely ahead of Luxemburg and behind Malta. It was also 20 out of 28 in the Climate Change Performance Index results for 2018.

This is about to change. A new, very ambitious, climate policy proposal was unveiled by the Dutch government in July based on a report produced in 2017 by PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. The proposal enjoyed the support of seven political parties who command a large majority in parliament. Even though there are a number of steps to go through over this year and next before final approval, it is expected that a Climate Agreement, ‘Klimaatakkoord’, will be concluded, involving also private and public organisations.

In parallel to this, agreement has been reached in parliament to enact a Climate Act, ‘Klimaatwet’, which embeds in law the key objectives of reducing emissions by 49% by 2030, and by 95% by 2050, relative to 1990.

Welcoming the developments, Green Party leader Jesse Klaver said: “The Dutch climate law is groundbreaking for the Netherlands…. Today seven parties, with a wide range of political ideologies, agreed on a Dutch climate law, currently the most ambitious climate law in the world.”

This will make Netherlands the eighth country in the world with such a policy, following in the footsteps of the UK, Mexico, Denmark, Finland, France, Norway and Sweden.

As well as smarting from severe criticism of its slow adoption of renewable energy relative to other European countries, the demise of Groningen might have contributed to this change of direction.

The new climate policy is aimed to redress the balance and achieve the Paris climate agreement goal of cutting CO2 emissions by 2050. It aims to do so through the implementation of infrastructural, technological and institutional changes.

The policy appears to benefit from strong social and political support in the country. As is often the case in the Netherlands, it relies on what is known as the ‘poldermodel’ – decision-making through consensus.

Current energy position

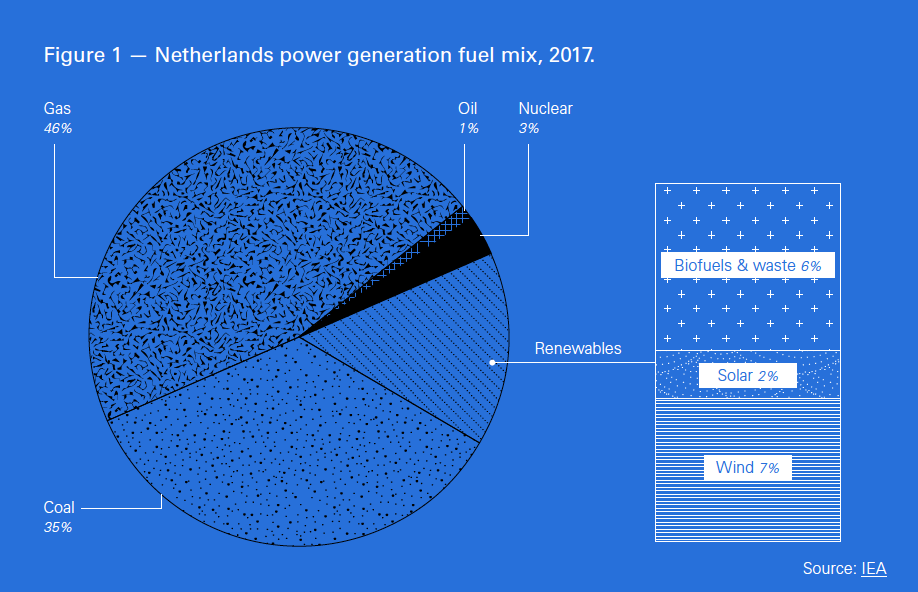

In 2017 the Dutch power sector had a transmission system operator (TSO), eight distribution system operators (DSO), over 25 producers, and 35 electricity retailers. The Netherlands has one of the most carbon-intensive electricity generation mixes in Europe, with 81% coming from natural gas and coal in 2016 (see figure 1).

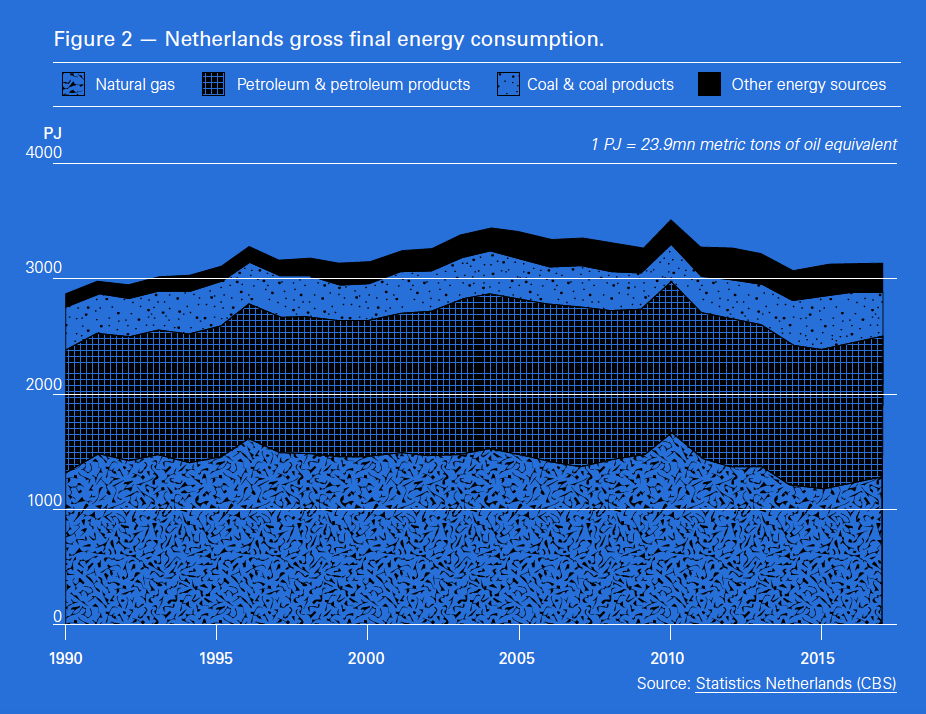

Gross final energy consumption increased by 10% between 1990 and 2017. Natural gas was the dominant fuel in 2017, with 41%. Fossil fuels provided 92% (see figure 2).

The share of renewable energy in the country’s overall primary energy mix was 6.6% in 2017, but even though it is expected to continue to grow, it will be difficult to reach the country’s 14% target by 2020.

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions fell by 12% in 2016, in comparison to 1990 levels, making it challenging to meet the 23% reduction target by 2020.

The new climate policy will require almost complete replacement of fossil fuels, including natural gas, by 2050. The magnitude of the challenge is clear: reaching near-zero CO2 emissions by 2050 will require far-reaching changes and public buy-in.

Natural gas production

The Netherlands is the second largest producer of natural gas in Europe after Norway, with most of its gas produced from Groningen, the largest onshore gas-field in Europe. Over its 60 years of operation it is estimated to have produced over 2 trillion m³ gas, with about 550bn m³ recoverable gas still remaining.

But extraction of gas from the gas-fields around Groningen has been causing tremors over the last few years. Houses have been damaged and this has angered the local population, leading to a political backlash. The result of this has been to reduce gas production down to 21.6bn m³/yr in 2017 – about 40% of its post-2000 peak production of 54bn m³ in 2013. In March the government announced that it plans to reduce production to 12bn m³ by 2022, tapering to zero output by 2030.

With over 90% of Dutch households and a substantial part of electricity production relying on gas from Groningen, its planned closure is bringing many complications.

It is also causing problems for Netherlands’ neighbours who have so far relied on its gas, although it might be a relief for some of GasTerra’s customers, who are tied into contracts they want to end. GasTerra has the exclusive right to market Groningen gas and is owned half by the Dutch government and a quarter each by the majors Shell and ExxonMobil.

Key elements of the Climate Agreement

The Climate Agreement, based on the PBL report, aims:

- to reduce GHG emissions by at least 49% by 2030 versus 1990;

- to reduce GHG emissions by 95% by 2050 versus 1990;

- to achieve a carbon-neutral electricity system through 100% elimination of CO2 emissions by 2050.

These constitute some of the most ambitious climate targets in the world and will be achieved by producing almost all electricity from renewables, solar, wind and other clean fuels.

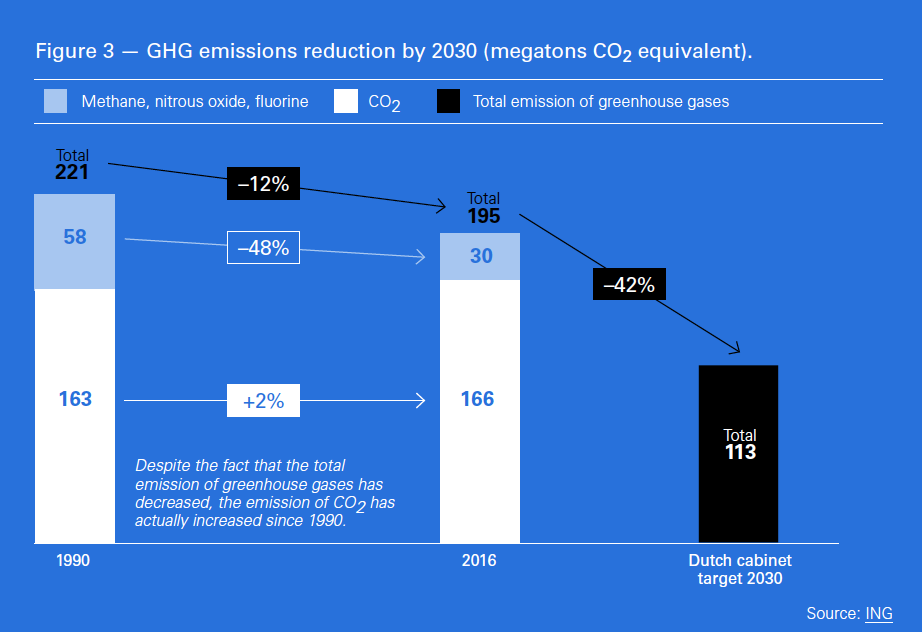

In order to achieve the 49% target, GHG emissions must be reduced from 221 megatons in 1990 to 113 megatons by 2030.

In order to meet this, a number of major emission reduction measures are proposed for each sector – power, industry, built environment, transport and agriculture. Key among these are:

- Closing all coal-fired power plants by 2030

- Boosting wind and solar power

- Constructing CO2 capture and storage capacity

- Emission-free car sales only, by 2030

- Reduce methane emissions

- Better energy performance of buildings

- About 1mn homes to be gas-free by 2030

- Higher tax on gas

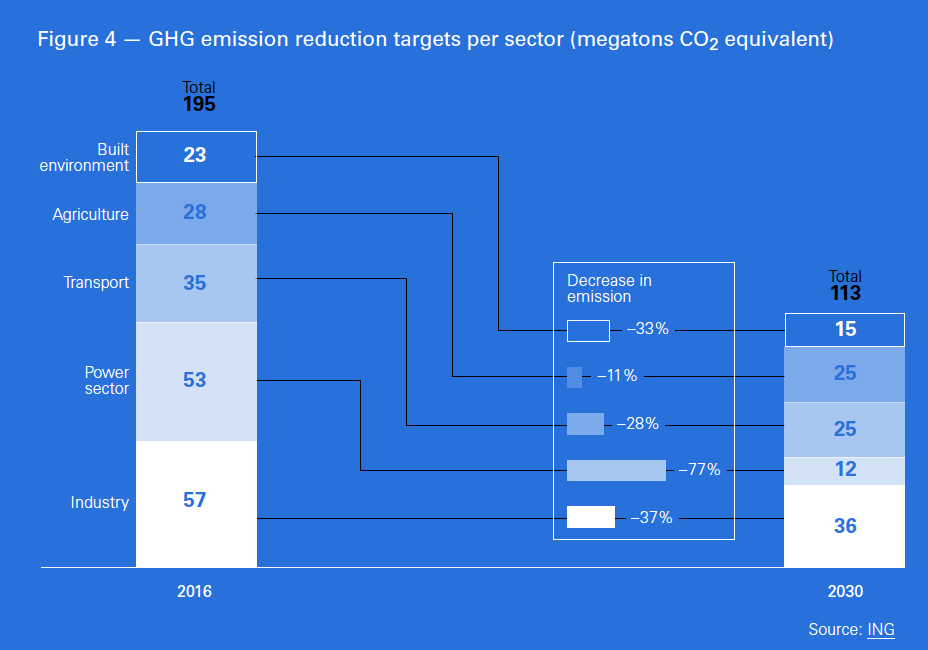

These and other numerous measures are the outcome of meetings over a four-month period involving over 100 organisations from all sectors, including government authorities, companies and interest groups, designed to achieve substantial reductions in GHG emissions. Most of these are in the power sector (see Figure 4). Not surprisingly, this is the sector where most reductions in emissions are planned to come from – a reduction of 77% is targeted between 2016 and 2030.

Clearly, the power sector faces a massive challenge. In 2016 about 81% of its fuel mix came from coal and natural gas. In order to meet the emission reduction target, this needs to be reduced dramatically and to be replaced by renewables. From about 9% of electricity produced from wind and solar in 2016, the new Climate Agreement expects these to provide over 60% by 2030 – a tall order.

The size of the challenge becomes even clearer when considering GHG emission reduction. Between 1990 and 2016 GHG emissions declined only by 12%, but the target now is to reduce these by 42% from 2016 to 2030.

A special Dutch-language website has been set-up which includes full details of the climate policy proposal.

Similar to the Paris Agreement, the Dutch Climate Agreement mostly specifies targets and timelines, but it does not include legal enforcement provisions. However, the 2050 carbon emissions target will be legally binding.

Implementation and challenges

Debate of the proposal has started. It is expected that all those involved will have committed themselves by the end of 2018, with the Climate Agreement and Climate Act to be signed in less than a year.

The proposal includes a key provision for the parliament and the cabinet to debate the progress on decarbonisation that has been made each year, based on independent advice from the Council of State, and they will use this to adjust programmes as necessary to stay on track. This debate will take place on a specific date: on the fourth Thursday of October, dubbed ‘Climate Day’. This will ensure it receives continuous public and political attention.

The government will then be required to issue a public report reviewing progress toward climate goals and laying out plans for the following year. In addition, the proposal provides that the climate plans will be reviewed, evaluated and updated every five years.

But the fact that it does not include legal enforcement provisions has drawn criticism, especially as the Dutch do not have a good record of meeting climate targets. Dennis van Berkel, legal counsel of the campaign group Urgenda, said the proposal was a “paper tiger” and a “largely symbolic act that only ensures that a yearly climate debate is organised, which reports on the route towards the 2050 target, but which gives very little assurance that real action is taken.”

The Netherlands is also taking the lead in a campaign to raise the European carbon emissions reduction target to 55% by 2030. This is supported by another 13 EU member states, calling on the EU to increase 2030 climate targets.

The proposed Climate Agreement poses enormous challenges to the country, some of the key ones being:

- Can the power sector respond in such a short length of time, by 2030, while still satisfying growing demand?

- Can the construction of numerous wind and solar plants, supported by electricity storage, and carbon capture and storage be achieved and respond timely to the challenge?

- Will the cost of this transformation be contained, ensuring a stable environment for investments while maintaining the country’s competitiveness in global markets?

- Who is going to pay this cost, including shutting down Groningen and existing coal-fired plants and making homes gas-free?

With such challenges and uncertainties it is perhaps understandable why the Dutch government has not made the 2030 targets legally enforceable.

The main losers will be fossil fuel producers, traders and distributors and the main beneficiaries will be wind and solar power companies and of course new clean energy industries. Interestingly, though, the Royal Association of Gas Companies of the Netherlands (KVGN), which includes Shell and Gasunie, has committed to the Climate Agreement and has proposed its own ambitious package of measures to achieve transition to a CO2-free 2050.

The proposal has certainly placed climate at the centre of Dutch politics. The next decade will be a period of major upheaval and uncertainty in the country’s energy sector, with implications for the economy – GasTerra estimates that some $50bn of gas will be left in the ground – and for security of energy supplies. But it could still emerge out of this successfully. It is a gamble the country appears willing to take.