[NGW Magazine] Southern Africa Still Looks to Coal

Southern Africa is expected to open twice as much coal-fired generation capacity as gas out to 2022, although there is a lot of gas within a relatively short distance that could be burned, given more regional co-operation or decisiveness.

An organisation representing 13 electricity generation utilities in 12 southern African countries has forecast that a total generation capacity of 30.646 GW will be commissioned between 2017 and 2022 across the region

Yet according to the Southern Africa Power Pool 2017 report, 10.896 GW of that (or 36%) will be coal-fired, while 7.863 GW (26%) will be new hydro-capacity, leaving gas trailing in third place with 5.644 GW expected to be commissioned out to 2022 – so just a fifth of projected new capacity.

That is less than in 2016, when of 4.180 GW new plants commissioned in the region, 995 MW (or 24%) were gas-fired in South Africa (670 MW), Mozambique (175 MW) and Tanzania (150 MW). The three countries have had access to gas production onshore southern Mozambique and onshore Tanzania for several years and related infrastructure.

A southern Africa analyst at specialist global risk consultancy Control Risks, Barnaby Fletcher, told NGW that greater regional co-operation could stimulate natural gas use in the next four years and beyond, although the lack of associated infrastructure could be a hindrance.

"Greater links between those [southern Africa] member states endowed with substantial natural gas resources and those without would undoubtedly help promote regional economic growth – as, indeed, would greater intra-regional trade in general,” he said. “A reliable supply of natural gas from Angola, Mozambique, South Africa or Tanzania could help ease energy constraints throughout the region or feed current under-developed downstream industries.”

But in inland markets such as Zimbabwe and Zambia, and northern Mozambique, access to gas will be limited and expensive, as there is limited or poor infrastructure, said Fletcher.

Angola was first to develop an LNG venture in the region and now Mozambique is set to open others in the 2020s, but these are firmly focused on export markets. Tanzania may later join the club. All three have significant offshore gas reserves. But until LNG ventures in the region are operating and profitable their operators – such as Italy’s Eni and US giant ExxonMobil in Mozambique – will not consider kick-starting a small local gas or LNG market.

New gas plants

Tanzania's $432mn Kinyerezi 2 Thermal Power Station, which was expected to produce 240 MW by December 2017, is one of the gas-fired units covered in the SAPP report. Its first phase was fully commissioned in March 2016, dispatching 150 MW to the grid. At 45% of national power output, Tanzania has the biggest share of gas-fired energy in the SAPP region, followed by neighbouring Mozambique at 41%.

Mozambique's state power utility EDM and South African gas producer Sasol are inching closer to completing a $1.2bn, 400-MW gas-fired plant at Temane in central Inhambane Province, 700 km north of the capital, Maputo. Construction is expected to start this year and be finished by 2021 and it will burn gas from the country’s Temane and Pande fields, operated by Sasol.

In Namibia, BW Offshore, a floating production ship owner, plans to launch a development of the offshore Kudu gas field, and is hoping to reach a final investment decision (FID) by June 2018 on the project. But it had originally aimed to take FID by the end of last year, and many have looked at monetising Kudu gas before as a fuel for onshore power generation, including Chevron, Shell, Tullow and even Gazprom – but all retreated from the proposition. The hope is that BW, with its expertise of floating production technology, the cost of which has been falling, may this time find a way.

Perhaps the surprising thing, in a region almost surrounded by vast offshore gas reserves, is that its electricity is so overwhelmingly coal-fired. However, its dominant economy is South Africa.

South Africa is the biggest coal-burning SAPP member: coal provides 85% (or 34.9 GW) of its installed generation capacity of 45 GW, owned by dominant state-owned generator Eskom. In contrast, Eskom has just four gas-powered plants with an installed generation capacity of just 2.4 GW. However, the South African Department of Energy's Integrated Resource Plan expects to reduce the share of coal generation capacity, to 46% by 2030, with gas projected to contribute 8% of the mix from 3%, according to a 2015 estimate.

Given that SAPP region can boast an estimated 600 trillion ft³ of gas resources – including 160 trillion ft³ offshore Mozambique alone, and 57 trillion ft³ offshore and onshore Tanzania – the dominance of coal in the region’s existing generation capacity is sobering.

Of SAPP’s total estimated 60 GW existing installed generation capacity, 62% is coal-fired, compared with 21% hydro, and just 1.5% gas. While there is progress in some countries, in others gas projects are stuttering.

Australia-based Tlou Energy believed it had government approval to build up to 100 MW of coalbed methane (CBM)-fired power generation capacity in Botswana, to monetise gas from the SAPP region's most advanced CBM project. But in February 2018 the government cancelled its approval for Tlou and another company Sekaname, and requested the power projects be re-tendered.

Tlou, which is sitting on proven and probable Botswanan CBM reserves of 40.8bn ft³, a fair share of which is thought commercially viable, must now decide whether to agree to the government re-tender, or instead look at projects that might use its CBM to generate electricity for export to neighbouring countries South Africa, Namibia, Zambia or Zimbabwe – all SAPP members.

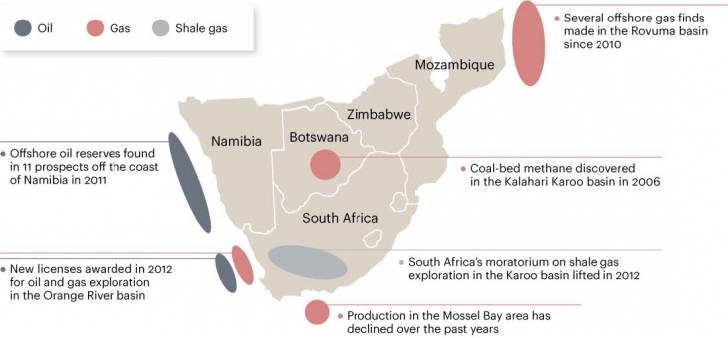

Recent developments in Southern African oil and gas

Credit: A.T Kearney analysis

Zimbabwe, Botswana’s fellow landlocked neighbour to the northeast, is now trying to revive interest in CBM exploration. State-owned Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC) lately invited bids to explore the northwest of the country, while Hwange Colliery is keen to attract suitors to develop its CBM blocks. Power generation would be an obvious outlet for any commercial discoveries. Both firms and two smaller ones failed to attract capital in the past but they hope that the peaceful overthrow of Robert Mugabe, in power since 1980, may rekindle interest. New president Emmerson Mnangagwa is seeking to reopen the country to foreign investment.

The political leadership in southern Africa has expressed keenness to stimulate greater investment into the natural gas value chain: in August 2017 at their summit Southern African Development Community (SADC) leaders agreed to establish an inter-state natural gas committee.

The structure, which is now being set up, will provide a formal platform for the 16 SADC member states to share ideas on how to attract investment into gas developments. (SADC has 16 members since the Comoro Islands officially joined at the August 2017 summit. Not all SADC member states are in SAPP.)

The new SADC committee could be useful in developing a high potential resource and evaluating available energy options, Zachary Donnenfeld, a senior researcher at Pretoria think-tank Institute for Security Studies has told NGW: "Gas would help with diversifying the regional energy mix."

South Africa itself however has been in political paralysis for months. Decisions on launching an international tender to develop new LNG import terminals, at Coega near Port Elizabeth and at Richards Bay on the east coast, linked to new gas-fired power projects at each site have been repeatedly postponed since 2016.

The Coega power project was to have been 1 GW and the one at Richards Bay twice that (2 GW); NGW understands that both projects are included in the SAPP's region-wide 5.644 GW gas-fuelled projection total. Their development by 2022 still looks uncertain.

South African energy minister David Mahlobo told an event in December 2017 that the country’s rate of power plant expansion might need to be scaled-back – an apparent admission by the government that it may be giving way to the interests of state incumbent Eskom.

Now that South Africa’s new president Cyril Ramaphosa is installed in power, all eyes will be on whether he revives the stalled international tender for gas-to-power investment and picks a new energy minister to drive this through.

Thulani Mpofu