[NGW Magazine] EU revamps carbon market

The EC’s decision to cut the amount of carbon certificates that are freely given away means the price could finally reach a meaningful level. But the decline in coal-fired power could create free lunches.

After two years of negotiations the European Council and the European Parliament agreed a deal on November 9 amending the European Union’s emissions trading scheme (EU ETS). This was based on the proposal made by the European Commission (EC) in July 2015.

Important for Europe, this agreement coincided with COP 23 that was then in progress in Bonn, and so it sent a strong message of Europe’s commitment to tackling carbon emissions.

EU commissioner for climate action and energy Miguel Arias Canete said the “landmark deal demonstrates that the EU is turning its Paris (COP 21) commitment and ambition into concrete action. By putting in place the necessary legislation to strengthen the EU ETS and deliver on our climate objectives, Europe is once again leading the way in the fight against climate change. This legislation will make the European carbon emissions market fit for purpose. I welcome in particular the robust carbon leakage regime that has been agreed and the measures further strengthening the market stability reserve.”

The main changes to EC’s proposal agreed between the European Council and Parliament are:

- Cutting emissions faster by speeding up the reduction of the oversupply of allowances, and a stronger market stability reserve (MSR);

- Adding safeguards to provide European industry with extra protection, if needed, against the risk of carbon leakage

- Several support mechanisms to help the industry and the power sectors meet the innovation and investment challenges of the transition to a low-carbon economy.

It was also agreed that the overall cap on the total volume of emissions will be reduced annually by 2.2%, compared with 1.74% today, so that the amount of emissions decreases faster.

In line with its Paris pledges, the EU plans to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030, compared with 1990 levels; and to increase the renewable energy contribution, so that it accounts for 27% of energy use. The EU ETS will be the main instrument used to achieve this target.

The deal must still be formally approved by the European Parliament and member states. It puts a cap on the amount of carbon dioxide allowed to be emitted by energy-intensive industry, power producers and airlines, pushing them to improve energy efficiency or switch to cleaner sources so that they keep within the ceiling.

The cap-and-trade system is the main tool used in the EU to regulate emissions by putting a cap at over 11,000 major industrial and power installations and airlines. Until this deal, the EU ETS suffered from a glut of permits meaning prices could not rise and discourage high carbon fuels, frustrating its intent.

The trick was to strike a balance between seeking to be ambitious on climate while still offering protection for energy-intensive industries. The risk is that the latter could be pushed into relocating abroad to avoid harsh climate legislation – the so-called carbon leakage.

Following the announcement of the deal, European carbon prices rose by 3.3% to about €8/metric ton. But in order to increase the incentive to become cleaner, this needs to rise appreciably to over €20/mt. A UK carbon capture and storage scheme at Teesside for example values carbon at £58/mt.

As far as Brexit is concerned, having had a say in how the ETS is shaped, most analysts believe Britain will remain part of the system, following a similar path to Norway.

Despite not being an EU member, Norway has companies that participate in the scheme. Switzerland is also joining the EU, following an agreement between the two to link their emissions trading markets. The document will be forwarded to the European Parliament for its consent and then the agreement should enhance carbon pricing throughout Europe and create a solid international carbon market. Switzerland will keep a separate system from the EU ETS, but participants in the EU ETS will be allowed to use allowances from the Swiss system for compliance, and vice versa.

This is a possibility for the UK to have a similar relationship with the EU, but there is scope for disagreement over which court has ultimate say in a dispute enforcement action, which is now the domain of the European Court of Justice.

And not everyone in the UK agrees with the EU ETS: economist Dieter Helm for example, in his document written for the UK government on the cost of energy, argues for a tax on carbon, not a trading system.

Market Stability Reserve

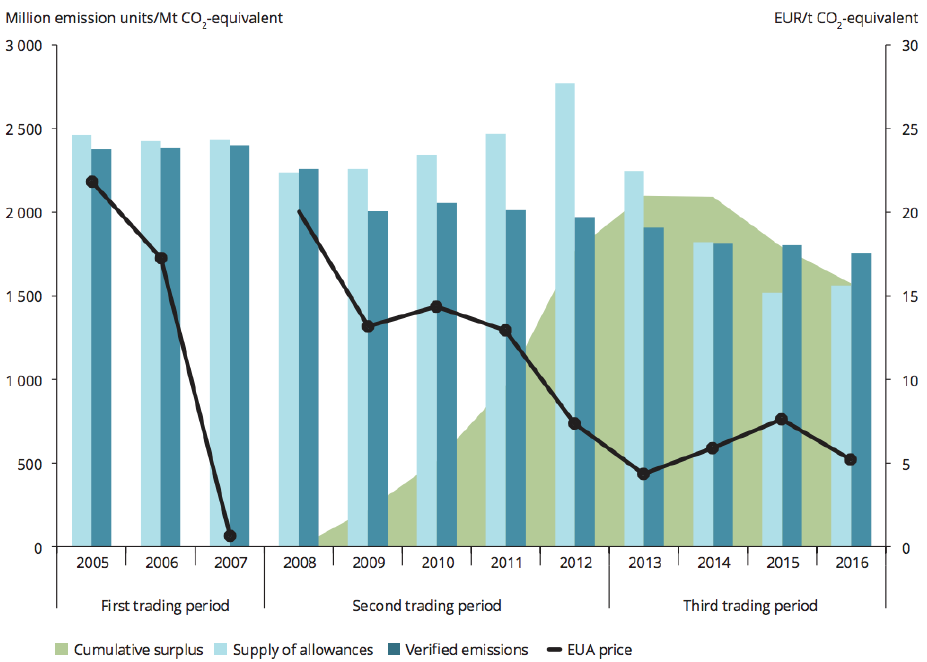

The first stage of the reform is to create the MSR, the aim of which is to correct the large surplus of emission allowances which has built-up in the EU ETS leading to low carbon prices (Figure 1), and to make the system more resilient in relation to supply-demand imbalances. This will be established in 2018 and will start operating from 1 January 2019.

Figure 1: Emissions, allowances, surplus and prices in the EU ETS, 2005-2016

NB: EUA = European Emission Allowances (Source: EEA)

The new deal doubles the rate at which the MSR absorbs excess allowances, as a short-term measure to strengthen prices. A new mechanism to limit the validity of allowances in the MSR will become operational in 2023 with the aim to reduce the oversupply of allowances on the carbon market.

The reform will strengthen the MSR to alleviate a market glut that slashed the price of emission permits by almost 70% over the past nine years. The number of allowances swept into the MSR will double over a five-year period starting in 2019. From 2023, permits in the reserve will start expiring if they exceed the amount sold at auctions in the previous year. Member states will also have the option of cancelling permits arising from power plant closures.

The EC also proposes to create support mechanisms to help the industry and the power sectors meet the innovation and investment challenges of the transition to a low-carbon economy. These include two new funds:

- Innovation Fund - extending existing support for the demonstration of innovative technologies to breakthrough innovation in industry

- Modernisation Fund - facilitating investments in modernising the power sector and wider energy systems and boosting energy efficiency in ten, lower-income member states

Coal-dependent Poland fought hard against the restriction on how the Modernisation Fund could be used and may still have reservations about the deal.

Impact of coal and gas

Coal accounts for almost a quarter of Europe’s power supply, but its use is declining, partly due to stagnant electricity demand and falling prices of cleaner alternatives.

With almost 40% of emissions covered by the EU ETS coming from coal power generation, an increase in carbon price will accelerate this decline.

But such an increase in the carbon price is not inevitable. As less coal is used, power utilities will need to buy fewer allowances which will lead to lower carbon prices. This in turn would not discourage further cuts in fossil fuel use. In order to correct this further, future, reviews of EU ETS may be required.

In addition, as Jochen Flasbarth, German state secretary for environment, warned at COP 23, higher carbon prices are not a “solution to it all” for EU’s climate policy. In order to switch from carbon-heavy coal to cleaner natural gas separate national policies may be required, additional to EU ETS.

This has been the approach in the UK where the imposition of a carbon tax, additional to ETS, has led to rapid decline of coal-fired power generation and a resurgence in gas demand.

China to follow suit?

The EU ETS is the world’s largest carbon market, but China is about to follow suit. China announced two years ago that 2017 would be the year in which it rolled out a national carbon trading scheme. However Xie Zhenhua, the country’s top climate official, said November 14 that preparations for a nationwide emissions trading scheme were “basically complete,” stopping short of giving a date for its launch. It is now expected to be in early 2018.

Once launched, this is expected to eventually become the largest scheme globally, bigger than EU’s ETS. The scheme is intended to reduce carbon emissions by creating a market cost for carbon emitters. Xie said: “The aim of the spot contract trading will be to reduce carbon…This is our sole aim.” He said the scheme would start by trading emissions from a selected group of companies from ‘mature’ industries and then build scale from there. A modest start – China is taking a cautious approach.

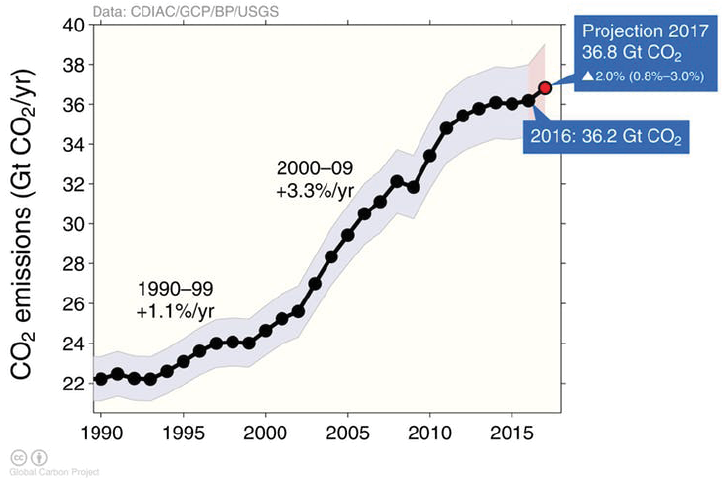

The delay comes after predictions that strong financial growth in 2017 may push Chinese carbon emissions up 3.5% and global emissions up 2% (Figure 2) after flat years.

Figure 2: Global carbon emissions

Source: Global Carbon Project

In the meanwhile, the EU and China are stepping up co-operation on carbon markets, ahead of the launch of China’s nationwide emissions trading system. The EU is supporting China to establish and develop its own system.

Implications

The EC believes that the outcome of the new deal significantly strengthens the ETS, maintains the environmental integrity of the system, supports innovation and modernisation in the energy sector and puts the EU on the road to achieve its Paris pledges.

Energy industry leaders appear to agree, saying that it would restore confidence in carbon trading. Kristian Ruby, Secretary General of Eurelectric said “Investors across Europe have received the much-needed legal clarity that will enable them to take better informed decisions on low-carbon investments…The deal sends a timely message of EU climate leadership that coincides with the ongoing COP 23 climate conference in Bonn. It also restores confidence in the long-term functioning of the EU ETS in time before the entry into operation of the MSR.”

However, not everybody is happy with it. Femke de Jong, EU policy director at Carbon Market Watch, was critical, saying: “Today’s deal ignores the urgency to reduce emissions quickly and hands out billions in pollution subsidies, meaning that the EU carbon market will continue to fail at its task to spur green investments and phase out coal.”

Further, based on predictions that global emissions will increase in 2017, the UN is pointing out that the gap between the scale of emission cuts needed and the commitments countries have made is alarmingly large. The longer countries delay the effort needed to close that gap, the harder it will be.

As a result, despite this deal, there are growing indications that the EU will need to revise its emissions pledge under the Paris Agreement, if it is to adhere to the target to limit global temperature rise to 2 0C by 2100. This may need to happen before 2030. If so, then the EU may need to revise ETS again.

Charles Ellinas

UK CCS ‘should not depend on a high carbon price’

Carbon capture and storage is critical as the lowest cost route of meeting the UK climate change targets, the CEO of industry group Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) Association Luke Warren told delegates at a briefing hosted by Oil & Gas UK in London November 15. It will also extend the life of offshore petroleum infrastructure, help to diversify the supply chain, and make use of a available skills.

CCS is also necessary if the UK offshore oil and gas industry is to continue to have its social licence extended, said Graham Bennett of consultancy DNV GL, predicting an earlier end to production if the industry cannot be seen to be working against climate change.

Nevertheless years after the idea was first mooted, no projects are ready yet for front-end engineering and design. Power generation is the obvious target for CCS, although industrial processes are also critical: these include the energy intensive production of steel, cement and chemicals. Warren said: “For the UK, CCS is the high-value option,” citing analysis that showed that an investment of £34bn ($45bn) could yield a benefit of £143bn, including CCS for third countries.

But apart from a government-funded competition to find a scheme worth investing in which was cancelled a few years ago, and the most recent announcement by the Oil & Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI), nothing has got off the drawing board, so “even if the government found £1bn ($1.32bn, the amount available in the competition) it could not spend it today.” That said, the government is now “back at the table and seeking to re-engage,” he said. There are five plans under consideration that could take a few tens of millions of pounds to develop into something that could then go to front-end engineering and design, in a couple of years, he said. But there has to be political commitment to it, especially as “under no circumstances do I see a carbon price high enough to drive CCS prior to the 2030s,” he said, adding that the long-term price of carbon ought to be high.

He said he was encouraged by the government’s adoption of the Clean Growth Strategy, but generally the UK is behind where it hoped to be by now, and it cannot afford any more delays.

Aside from the OGCI plan for capturing and storing the CO2 from an unidentified gas-fired power plant, the plans are for: a decarbonising hydrogen for industry in the Liverpool and Manchester regions, overseen by gas distribution grid operator Cadent, which could use storage in the UK East Irish Sea; equipping an industrial site in Teesside with CCS, planned by the Teesside Collective; decarbonising the Ineos/PetroChina-owned Grangemouth oil refinery in a project known as Caledonian Clean; and H21, which involves decarbonising the Leeds heating network in Yorkshire.

Warren said on the sidelines of the briefing that the carbon price for Teesside worked out at £58/metric ton, far higher than the price of the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), although cheap compared with the cost of cavity wall insulation schemes. The plan is to scale back progressively the number of allowances tradable from 2020, which could tighten supply and so push carbon prices up.

William Powell