[NGW Magazine] New Dutch Govt Turns off the Taps

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 20

By Koen Mortelmans

The new Dutch government wants to close coal-fired power plants and shrink natural gas use, as it sets the Netherlands a more ambitious target to decarbonise than the average target the EC has set for the EU.

Seven months after the election of a new Dutch parliament, four political factions have reached an agreement to form a new government. Among the main priorities of this government are the definitive closing of the remaining coal fired power plants and the capture and storage of CO2.

The new government is headed by Mark Rutte (VVD), who has been prime minister since 2010; and composed of ministers from the VVD (conservative liberals), CDA (Christian democrats), D66 (Progressive liberals) and CU ((very) conservative Christian democrats) parties.

The Dutch electoral system means that even with the support of four parties, parliamentary support for the new government (76) is only two seats larger than the opposition (74). The CU only became involved in the negotiations after Groen Links (progressive greens) dropped out.

Groen Links was the main victor of the elections, while the results of CU are generally stable from election to election. It finds most of its voters in the so-called Bible Belt. They may have very different ethical objectives but the CU is against coal just as much as parties on the left.

Concerning climate, Rutte III – so called because it will be his third term as prime minister – wants to be more ambitious than the European Union. Europe aims to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases to 51% of the 1990 level, by 2030, but this is not enough for the new Dutch government which wants to achieve just 45% emissions against that baseline.

It will develop a national energy and climate plan, including detailed long-term actions, to offer industrial sector organisations and companies a degree of security.

In 2019, a few years after the Paris agreement on climate change, the Netherlands will take the opportunity of raising European ambitions to the Dutch level. If this turns out to be impossible, it will try to do this with only the neighbouring countries.

In order to stop these efforts merely leading to higher emissions elsewhere in the EU, collateral actions, such as restricting emissions trading certificates, might be necessary.

Carbon Capture & Storage

Most of the emissions reduction will be achieved by the capture and storage of CO2 in industry and in waste incinerators. Another main measure to achieve the 2030 CO2 ambition is the definitive closing of the remaining five coal-fired power plants, which now account for almost a quarter of the country’s total CO2 emissions.

The government agreement only says that this kind of electricity production will belong to the past by 2030, without stipulating a scenario for the closure of even one such plant at an earlier date. All it says about timing is that agreements will be made with the sector.

The use of biomass as a secondary fuel in coal-fired power plants however will end in 2024. Therefore, the government will stop subsidising this fuel. Germany’s RWE will probably be the only company to enjoy them as long as that, since fellow German Uniper and French Engie have already adapted their plants for biomass.

In the short term, Rutte will reserve more space in the Dutch part of the North Sea for offshore wind farms and impose a minimal price for CO2 of €18/metric ton starting in 2020, steadily rising to €43/mt in 2030. Analysts think that a CO2 price of €20/mt will make gas-fired power plants more profitable than the two oldest coal fuelled plants; and at €35/mt they will have an advantage over the three more recent coal fired plants.

Gas use must diminish

This policy would expand the demand for natural gas, as gas-fired power plants use a lot. On the other hand, the intention to cut gas demand in households is firm. The current obligation to connect new homes to the gas distribution grid will be replaced by the need to obtain district heating or a connection to an electricity grid with augmented capacity. Taxes on electricity will go down, but on gas they will rise.

Today, in new neighbourhoods a gas distribution grid is part of the standard infrastructure. At the end of the legislature however the standard will be to have no gas. In the next five years, between 30,000 and 50,000 existing houses must be converted each year to run on alternative fuels. From 2022, this number must rise to 200,000 houses/year.

By 2050, the entire Dutch housing stock – 6mn houses according to the government, but this number is disputed – must be gas-free.

Netbeheer Nederland, the lobby group for Dutch energy distribution grid managers, is happy about the substitution of the obligation for a gas connection with one for district heating. It also calls for the new infrastructure to be managed by independent organisations.

Rutte III recognises the fact that natural gas production can cause tremors. The four government parties say that safety must have priority. The gas output of the largest Dutch gas field, Groningen, will fall to 20.1bn m³ in about four years.

This is 1.5bn m³/yr lower than the level most recently stipulated by the resigning government. Rutte III aims to realise this decrease by lowering demand by 3bn m³ each year. The remaining 1.5bn m³ will be used as a buffer to secure the supply to households and the stability of the subsoil.

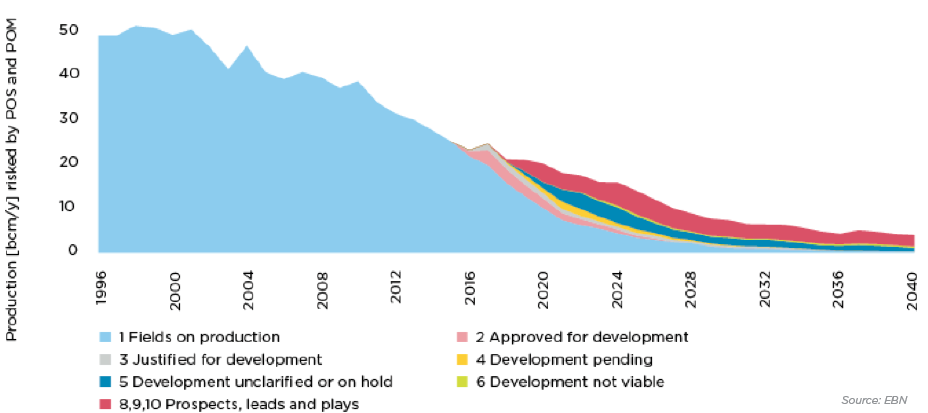

Rutte III will not allow new natural gas exploration licenses onshore either, while offshore, the small fields that used to provide a half of the Dutch gas output, are in decline anyway and decommissioning, as in the case of the UK, is the next big story (see graph).

Happy coincidence

“What a coincidence that gas production will remain a little bit higher than 20bn m³/yr, the generally mentioned minimum level that allows profitable exploitation,” is the subtle reaction of environmental organisation Milieudefensie. “Can this choice be inspired by the need for profits more than safety?”

The financial responsibilities for making good the housing stock will remain with NAM, the Shell-ExxonMobil joint venture that operates the Groningen field. NAM will have no say in deciding what claims are actually caused by gas exploitation. This will be the job of an independent auditor.

Dutch small fields’ historical & forecast production

Disputes about the size of the compensation between public and private authorities will not affect citizens anymore. Tensions in the sub-soil, caused by gas exploitation since the 1960s, will not disappear when production is lowered or halted. Therefore, a special programme will be activated to strengthen existing houses and other buildings.

To guarantee the economic revival of the province of Groningen, where the largest gas fields are, a special fund will be created. Starting in 2018, it will be fed with 2.5% of the gas revenues. This is estimated to amount to €50mn/year. As well as the material needs, the fund will also cover adapted care for people having psychological problems caused by the damage.

Koen Mortelmans